By Caio Mario S. Pereira Neto1

As pointed out in the OECD’s recent Background Note (OECD 2022), interim measures are an important tool designed to deal with imminent danger to competition, preserve market conditions during antitrust investigations, and improve the overall effectiveness of competition law enforcement. This tool allows national competition authorities (“NCAs”) and/or courts to take immediate action to preserve competition during ongoing investigations. Given its intrusive nature at the early stage of an investigation, interim measures are (and should be) exceptional actions, taken only in cases that cannot wait for a decision on the merits, after a comprehensive analysis.

This article discusses the challenges of imposing interim measures at the beginning of an investigation when NCAs or courts inevitably only possess limited information and thus operate under high uncertainty. The analysis focuses on dominance cases where the core concern is the exclusion of rivals and damages to the competitive process, which might become hard to reverse.2 These cases have been in the spotlight lately, especially in investigations involving digital markets, with network effects and winner-takes-most dynamics. Although some of the insights may also apply to interim measures in other types of procedures (e.g. merger analysis), they will not be discussed here. The examples will be centered on administrative regimes, where the NCAs decide on interim measures, but most conclusions also apply to regimes based on courts’ decisions.

Section I presents the context in which interim measures are currently discussed and the general legal conditions for their adoption in most jurisdictions. Section II compares the provisional remedies adopted by interim measures with final remedies adopted after a finding of infringement, identifying resemblances and contrasts between these two types of decisions. Section III builds on the discussion about provisional remedies to develop an error-cost framework to deal with interim measures. Finally, Section IV presents a brief conclusion, summarizing key elements to consider when NCAs face decisions about interim measures.

I. Interim Measures: Current Context and Legal Conditions

Interim measures have been an available tool in many jurisdictions for several years. However, the debate about whether and when NCAs should use interim measures has intensified, as concerns have mounted about lengthy investigations in dynamic markets. A fear, therefore, is that, in the absence of measures to preserve competition during complex investigations in these fast-changing markets (often involving the development of new theories of harm), irreparable damage to competition may occur before reaching a final decision. Although the use of interim measures has been reinvigorated recently, especially in unilateral conduct cases, calls are still being made for more frequent use of this tool (e.g. Heinemann 2021; Kadar 2021) and for adjusting and softening legal standards to make it easier to adopt these measures (e.g. UK Report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel, Mantzari 2020).

In recent years, multiple jurisdictions have adopted interim measures in different contexts involving dynamic markets. For example:

- in 2019, for the first time after 20 years, the European Commission applied interim measures to Broadcom, suspending specific exclusionary provisions in agreements to sell chipsets used for TV set-top boxes and modems (EU – Broadcom Case);

- in 2021, the Brazilian Competition Authority (“CADE”)3 issued interim measures limiting exclusive dealing in two separate cases involving digital platforms operating, respectively, food delivery and fitness aggregator apps (Brazil – iFood and GymPass Cases); in 2020, the Swedish authority issued a similar interim measure suspending exclusivity clauses practiced by a fitness aggregator app (Sweden – Bruce Case);

- in 2020, the French Competition Authority, Autorité de la Concurrence,4 issued an interim measure obliging Google to negotiate in good faith with publishers, press agencies, and collective management organizations to establish the compensation due by Google to the latter for any reuse of protected content on its services (France – Google Related Rights Case);

- in 2021, the Competition Commission of India (“CCI”) issued an interim measure against two online travel agencies (“OTAs”), ordering them to re-list the claimants on their platforms, after having excluded the claimants in pursuance of a commercial arrangement with one of the claimants’ competitors (India – OTAs Case).

Despite national specificities, jurisdictions that allow the adoption of interim measures usually require the meeting of two legal conditions: (i) a sufficient likelihood of establishing an infringement on the merits after the complete investigation (fumus boni iuris) and (ii) an urgent need to act to avoid serious harm to competition (periculum in mora). The first condition demands a careful evaluation of the potential outcome of an ongoing investigation, considering the theories of harm under discussion, the evidence available at the time of analysis, and the standards to characterize infringement in each jurisdiction (i.e. this analysis amounts to a prima facie finding of infringement). The second condition requires imminent harm of a relevant nature, usually perceived as “irreversible” or at least “irreparable” (see OECD 2022, p. 12). Meeting this condition implies a balancing exercise, considering that the early intervention may avoid damage to competition but also harm the investigated party(ies) or even the market and consumers.

Both conditions require evaluations based on limited information and significant uncertainty. In other words, according to the available evidence, authorities must make their best assessment to predict how likely a future finding of infringement is and whether there is current or imminent harm to competition, and, if so, how intense that injury is or could be. This type of assessment shares some similarities with decisions to impose remedies after a finding of infringement, which are worth exploring.

II. Interim Measures v. Final Antitrust Remedies: Resemblances, Contrasts, and Challenges of Decisions under Different Levels of Uncertainty

Interim measures are also referred to as “remedies of a temporary nature” (OECD 2022, p. 13), “provisional remedies” (Giosa 2020, p. 2), “a quick, temporary remedy that […] does not fully fix the anticompetitive issue” or just a “quick relief” (Feases 2020, pp. 4 and 18). Thus, as a way of thinking about interim measures, it may be helpful to compare these temporary interventions with final remedies, identifying similarities and contrasts that may shed light on challenges presented by these enforcement tools.

At a high level, interim measures and final remedies present some relevant similarities as they are both: (i) intrusive interventions that affect the investigated party; (ii) aimed at correcting anticompetitive conducts and avoiding harm to the market; (iii) mechanisms which require balancing the expected positive impact of the remedy on the market and to the public interest, on one side, against the rights and freedoms of the investigated party and potential adverse effects to the market and consumers, on the other side; (iv) prone to Type I and Type II errors, considering the uncertainty around the finding of infringement and the effectiveness of the remedy chosen (be it temporary or not). In addition, both (v) require monitoring and (vi) may require adaptation over time.

However, interim measures and final remedies also present relevant differences, including those about their specific goals, the timing of the decisions, the information available at the time of the analysis, the type of remedy that may be adopted, and reversibility requirements. The table below presents a brief comparison, highlighting relevant differences.

Table 1 – Interim Measures v. Final Remedies

| Interim Measures | Final Remedies | |

| Objective/

Functions |

Protecting competition during the investigation when there is imminent harm in the absence of interim measures.

Preserving NCAs’ ability to impose meaningful final remedies if an infringement is found after the full investigation. |

Restoring competition upon the final finding of infringement.

Permanently ceasing the infringement and its anticompetitive effects. |

| Conditions for adoption | Predictions about the investigated conduct: (i) the likelihood of an infringement being established (fumus boni iuris) and (ii) the urgency to act to avoid irreparable harm to competition (periculum in mora).

A balance between the harm to be avoided and the potential harm caused by the temporary intervention. |

A definitive conviction for a competition law infringement meeting the standards for characterizing the wrongdoing and the burden of proof required in each jurisdiction. The standard of proof is naturally higher for final decisions than interim measures. |

| Nature of obligations imposed | Because of reversibility concerns, temporary remedies imposed by interim measures are usually limited to behavioral obligations (OECD 2022, p. 14). Structural remedies must be avoided, considering their irreversibility and error-costs. (Feases 2020, p. 22)

Preference is given to “negative” obligations, restraining specific actions (e.g. prohibitions, suspension of contractual provisions, limiting future contracts), which are easier to enforce than “positive” orders that impose new actions (e.g. obligations of interoperability). |

A more comprehensive range of behavioral or structural remedies, including “positive” orders and eventual divestment, as required and permitted by circumstances. |

| Reversibility of the remedy | The very nature of interim measures requires the reversibility of the remedy. Should the final decision dismiss the case without any finding of infringement, the interim measure must be fully reversed. Even during investigations, interim measures may be fully reversed if the authorities believe the conditions that demanded intervention no longer exist (e.g. Belgium Competition Authority, in Richards, 2018). | Final remedies do not require reversibility, as they aim to permanently cease the infringement and eliminate the anticompetitive effects identified during the investigation. |

| Adaptability/ Room for review | Adaptability means leaving room for adjustments over time. Interim measures may be adjusted if circumstances change. For example, additional evidence may show more or less concern about the practice and its effects; the measure imposed may be considered insufficient or excessively broad; market conditions may change, etc. (e.g. Swiss ComCo, in Craig, 2020). | Final remedies may also be reviewed and adapted if they are considered insufficient or excessive to deal with the infringement identified or if market conditions change substantially. However, after the finding of infringement in a final decision, the focus of review shifts to the effectiveness of the remedy. |

| Duration | Interim measures are always of a temporary nature, and they may last only until the final decision of the competition authority. | Final remedies may have a temporary nature or a permanent nature. They may also require some degree of periodic review. |

| Level of uncertainty when imposing remedies | In the early stages of an investigation, uncertainty about the existence of an infringement and actual harm to competition is always higher than at the end of the investigation.

There is also uncertainty about the impact of the temporary remedies imposed by interim measures during the procedure, both on the investigated party and the market. |

At the end of the investigation, NCAs decide on the existence of an infringement based on a wide array of information gathered during the investigation, reducing uncertainty. However, in complex cases, there is a residual risk of Type I and Type II errors (over- or under-enforcement), as authorities may mischaracterize infringements.

In addition, there is always uncertainty about the efficacy of the imposed remedy. Finally, there is a risk of substantial new developments in the market (e.g. innovative, disruptive entrants), radically changing the context and requiring adaptation of the remedy. |

This brief comparison is sufficient to show that authorities face more significant constraints when applying provisional remedies: (i) limited information available at the early stages of an investigation; (ii) the temporary nature of the remedy; (iii) a clear need for complete reversibility of the measure; (iv) need for adaptability over time; (v) more significant burden to balance the benefit of the provisional remedy against the harm of an immediate intervention on defendants. In addition, when deciding to intervene, authorities need to observe the procedural rights and protections of the defendants, considering the presumption of innocence and the freedom of enterprise protected in most jurisdictions. These constraints make it particularly challenging to impose interim measures.

Considering these similarities and differences can help frame decisions about interim measures under an error-cost approach, which brings about certain policy implications.

III. Interim Measures as Decisions to Grant Temporary Relief under Uncertainty: Applying an Error-Cost Approach

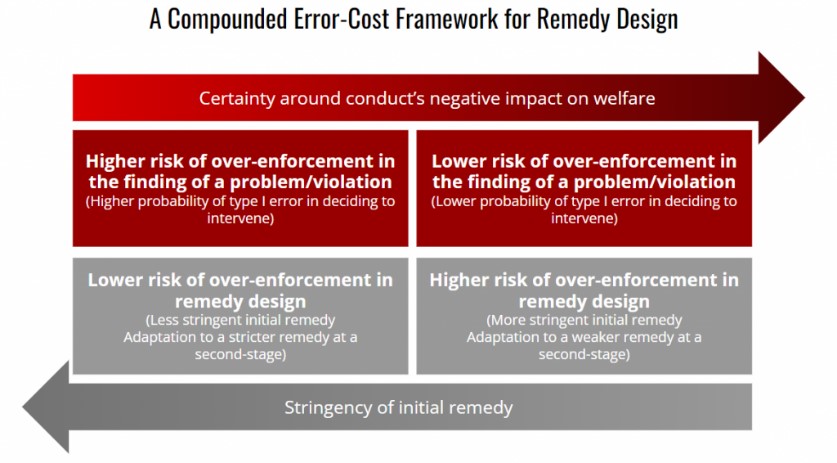

In prior work co-authored with Filippo Lancieri, summarized in ProMarket, we discussed how decisions about remedies are always taken under uncertainty, and are therefore open to Type I and Type II errors. This point highlights the importance of constructing an error-cost framework for analysis. Even when authorities and courts are right regarding the findings of infringement, they may be wrong about their choice of remedy and harm welfare by imposing an overly broad or overly narrow measure. For this reason, we identified “compounded (doubled) error risks” when designing any remedy, reflecting the uncertainty about the finding of infringement and the uncertainty about the remedy choice itself.

This compounded error risk requires a two-step evaluation by the authorities, balancing: (i) how certain they are that there is an infringement at the time of the decision; and (ii) how harmful the alleged infringement is to market competition and/or to the general welfare.

The more confident the authorities are about a particular infringement (i.e. low risk of over-enforcement at the infringement level), the more they should be willing to impose stringent remedies (i.e. they may take more risk of over-enforcement at the remedy level). In contrast, when authorities are less sure about the infringement (e.g. when they are testing the limits of new theories of harm or when they have limited evidence), they should be more cautious about imposing stringent remedies, avoiding the risk of compounded errors in the definition of infringement and the design of remedies. Thus, authorities’ willingness to take risks of overly broad remedies should be inversely proportional to their certainty about the infringement, and vice-versa, as illustrated below.

Source: https://www.promarket.org/2022/03/08/antitrust-remedies-digital-platforms-regulators/

This evaluation should be made together with an analysis of the intensity of the harm to the market. To the extent that narrow remedies can limit the damage to the market, they would be preferable. However, if authorities are confident that narrow remedies would be insufficient to limit the harm, they should adopt broader remedies, even under the risk of over-enforcement.

Unlike infringement decisions, remedy decisions are not binary. Instead, they can be fine-tuned to match the remedy, on one side, to the levels of certainty about the characterization of the infringement and, on the other side, to the intensity of harm. Remedies can also be reviewed and adapted if these evaluations change, leaving more room to correct errors over time.

This general framework can apply to any decision regarding remedies, including provisional remedies imposed through interim measures. Because these interim decisions are based on more limited information, with a higher degree of uncertainty, and under additional constraints, this usually suggests the need for caution and the adoption of a more targeted temporary remedy compared to a remedy at the final ruling. Indeed, less extensive evidence should lead to narrower interim measures (, p. 46). As discussed in the prior section, the need for a cautionary approach is also incorporated in some other features of interim measures, such as the preference for behavioral remedies and the requirement of reversibility.

However, if specific circumstances point to a high degree of certainty about the infringement at the early stages of the investigation (fumus boni iuris) and immediate and irreparable harm (periculum in mora), broader provisional remedies may also be applicable. Such was the situation in the EU – Broadcom Case, judging from the language used in the decision, which pointed to a substantial degree of certainty about the infringement and the harm to the market. At the time, Margrethe Vestager, Commissioner in charge of competition policy, declared: “We have strong indications that Broadcom, the world’s leading supplier of chipsets used for TV set-top boxes and modems, is engaging in anticompetitive practices. Broadcom’s behaviour is likely, in the absence of intervention, to create serious and irreversible harm to competition. We therefore ordered Broadcom to immediately stop its conduct.”

Caminade, Chapsal and Penglase make further contributions to an error-cost framework, specifically in the context of interim measures (see also Caminade OECD Note 2022). Their main insight is that authorities should try to compare the “relative magnitudes” of irreparable harm (i) to plaintiffs, consumers, and other third parties from wrongly failing to impose an interim measure (under-enforcement – Type II error) (ii) and to the defendants, consumers and other third parties from wrongly imposing the provisional remedy (over-enforcement – Type I error). They hold that the asymmetry of harms is more critical than the specific magnitude of each harm. Thus, authorities should be inclined to adopt the interim measure whenever the harm from Type II errors is potentially higher than the harm from Type I errors.

The same authors argue that the relative magnitudes of the harms may change throughout the investigation as the intensity of the two harms may shift, an insight that reinforces the idea that authorities should be open to reviewing interim measures and changing provisional remedies over time. This idea of adaptability of the remedy according to the change in circumstances seems particularly important in more dynamic markets, where significant new developments are more likely to occur during investigations.

Finally, Caminade, Chapsal and Penglase also propose that authorities should have a minimum threshold of the likelihood of infringement to adopt an interim measure. This approach avoids imposing provisional remedies in prima facie weak cases, even if the expected harm is intense and asymmetric. This proposition is in line with Lancieri and Pereira Neto’s perspective about the relevance of certainty of infringement to avoid compounded error effects in adopting remedies. This threshold of the likelihood of infringement varies across jurisdictions, translating into different evidentiary standards for the imposition of interim measures (OECD 2022, p.12). However, once this minimum threshold is reached, it seems that the analysis should shift to (i) the magnitude of relative asymmetry of harms and (ii) the extension of the remedy (i.e. narrower or broader).

Taken together, these insights can help better structure the decision on interim measures, acknowledging the inherent uncertainty about adopting provisional remedies at the early stages of an investigation and taking the balancing of risks of different types of errors seriously.

IV. Conclusions

Interim measures are increasingly important tools to guarantee the effectiveness of competition policy. In fast-moving, dynamic markets, lengthy investigations about the abuse of dominance may lead to decisions that come too late and can do too little. In this context, it is not surprising that NCAs are under pressure to take quicker action and avoid irreparable harm to competition, adopting provisional remedies at the early stages of the investigation. However, acting earlier means acting based on more limited information, under increasing uncertainty, and more exposed to errors that may negatively affect the investigated parties and the competition in the market. In this sense, as discussed in Section II, the stakes are higher in decisions about provisional remedies than in decisions imposing final remedies, given the additional constraints involved in the former (e.g. need for reversibility, concerns about adaptability).

Thus, it is helpful to think about decisions regarding interim measures from the perspective of an error-cost framework. Given the limited information available at the time of analysis, the decision to adopt (or not) an interim measure should be taken considering (i) how confident the authority is about the characterization of an infringement (establishing at least a minimum threshold of certainty); (ii) how sure the authority is about the harm to competition and general welfare; and (iii) the relative magnitude of (a) the harm of Type II errors (wrongly failing to impose a provisional remedy) vis-à-vis (b) the harm of Type I errors (wrongly imposing a provisional remedy) in a particular case. Accordingly, the interim measure should be adopted when there is a high level of certainty about (i) and (ii) and when (iii) (a) is considered more intense than (iii) (b).

If this analysis leads to the decision to impose an interim measure, the degree of certainty or uncertainty should also inform the willingness to adopt broader or narrower provisional remedies (increasing confidence levels recommend adopting broader and more stringent provisional remedies, and vice-versa). Finally, authorities should be open to reviewing interim measures during investigations, adjusting or complementing the provisional remedies as needed, or even revoking the decision altogether.

This framework is not biased toward action or inaction of competition authorities, as it acknowledges the potential harm from errors in both directions, trying to balance them. However, one must be cautious not to create a bias by assuming that one type of error is always more harmful than the other (i.e. harm from Type I errors always considered higher than harm from Type II errors, or vice-versa). In other words, the proposed approach is highly dependent on a case-by-case analysis and will lead to different outcomes in different contexts.

Insights from this error-cost analysis can be useful to make clear the trade-offs involved in each decision on interim measures. Once the decision to intervene is taken, this analysis can also help choose among available provisional remedies (narrower or broader). Finally, this framework highlights the importance of reviewing and adjusting the original decision as more information becomes available and circumstances change, shifting the results of the initial analysis.

References

Autorité de la Concurrence, Décision n° 20-MC-01 du 9 avril 2020 relative à des demandes de mesures conservatoires présentées par le Syndicat des éditeurs de la presse magazine, l’Alliance de la presse d’information générale e.a. et l’Agence France-Presse, https://www.autoritedelaconcurrence.fr/sites/default/files/integral_texts/2020-04/20mc01.pdf.

Azambuja, João Felipe Achcar de, Interim Measures Applied to Digital Platform Exclusivity Cases: The Brazilian Recent Experience. 30 September 2022. Competition Policy International, https://www.competitionpolicyinternational.com/interim-measures-applied-to-digital-platform-exclusivity-cases-the-brazilian-recent-experience/.

Caminade, Juliette; Chapsal, Antoine; Penglase, Jacob, Interim Measures in Antitrust Investigations: An Economic Discussion, Journal of Competition Law & Economics, Vol. 17, Issue 2, June 2021, Pages 437–457, https://doi.org/10.1093/joclec/nhaa027.

Caminade, Juliette, Interim Measures in Antitrust Investigations: An Economic Discussion = Note by Juliette Caminade, 21 June 2022, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WP3/WD(2022)22/en/pdf.

Craig, Emily, Swiss authority lifts watchmaker delivery obligation, Global Competition Review, 15 July 2020, https://globalcompetitionreview.com/article/swiss-authority-lifts-watchmaker-delivery-obligation.

Competition Commission of India, Case No. 14 of 2019 and 01 of 2020, https://www.cci.gov.in/images/antitrustorder/en/142019-and-0120201652511256.pdf.

European Commission, CASE AT.40608 – Broadcom, decided on 16 October, 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/cases/dec_docs/40608/40608_2791_11.pdf.

European Commission, Antitrust: Commission imposes interim measures on Broad-

com in TV and modem chipset markets, October 15, 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_19_6109.

Feases, Alexandre Ruiz, Sharpening the European Commission’s Tools: Interim Measures (Augustus 12, 2020). TILEC Discussion Paper No. DP 2020-020, SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3686585 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3686585.

Lancieri, Filippo; Pereira Neto, Caio Mario S., Designing Remedies for Digital Markets: The Interplay Between Antitrust and Regulation, Journal of Competition Law & Economics, Vol. 18, Issue 3, September 2022, Pages 613–669, https://doi.org/10.1093/joclec/nhab022.

Lancieri, Filippo; Pereira Neto, Caio Mario S., Designing Better Antitrust Remedies for the Digital World, Promarket, March 8 2022, https://www.promarket.org/2022/03/08/antitrust-remedies-digital-platforms-regulators/.

Giosa, Penelope, Interim Measures: A remedy to deal with price gouging in the time of Covid-19?, CPI Antitrust Chronicle, September 2020, https://www.competitionpolicyinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/08-Interim-Measures-A-Remedy-to-Deal-with-Price-Gouging-in-the-Time-of-COVID-19-By-Penelope-Giosa.pdf.

Heinemann, Andreas. Competition Law in Need for Speed. Concurrences, Issue 4, 2021, pp. 2-4, https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/212264/1/Competition_law_in_need_for_speed.pdf.

HM Treasury; Furman, Jason, et al. (2019). Unlocking digital competition, Report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel. https://doi.org/10.17639/wjcs-jc14.

Kadar, Massimiliano, The Use of Interim Measures and Commitments in the European Commission’s Broadcom Case, Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, Vol. 12, n. 6, June 2021, Pages 443–451, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeclap/lpaa105.

Konkurrensverket, Swedish Competition Authority accepts commitments from training company, 7 July 2020, https://www.konkurrensverket.se/en/news/swedish-competition-authority-accepts-commitments-from-training-company/.

Mantzari, Despoina, Interim Measures in EU Competition Cases: Origins, Evolution, and Implications for Digital Markets, 17 August 2020, https://academic.oup.com/jeclap/article-abstract/11/9/487/5893074.

Richard, Matt, Belgium dismisses interim measures request on second look, Global Competition Review, 09 October 2018, https://globalcompetitionreview.com/article/belgium-dismisses-interim-measures-request-second-look.

Schweitzer, H. (2020), The New Competition Tool – Its institutional set up and procedural design: expert study, https://op.europa.eu/s/vUwC.

OECD, Interim Measures in Antitrust Investigations, OECD Competition Policy Roundtable Background Note, 2022, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/interim-measures-in-antitrust-investigations-2022.pdf.

Pereira Neto, Caio Mario S., Pastore, Ricardo Ferreira, & Paixão, Raíssa. Competition Law Enforcement in Digital Markets: The Brazilian Perspective on Unilateral Conducts. The Antitrust Bulletin, 67(4), 2022, 622–641, https://doi.org/10.1177/0003603X221126159.

Click here for a PDF version of the article

1 Caio Mario S. Pereira Neto is Professor of Law at FGV Law School, São Paulo, Brazil, and holds a Master of Laws (LL.M.) and a Doctorate (JSD) from Yale Law School (USA). Pereira Neto is a founding partner at Pereira Neto | Macedo | Rocco Advogados, São Paulo, Brazil, where he heads the competition and regulatory practices.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Alison Jones, Antonio Capobianco, Daniel Westrik, Filippo Lancieri and Gaetano Lapenta for helpful comments on a prior version of this article and Antonio Belizario, Raíssa Paixão and Vinícius Goulart, for their research assistance. Any errors are my own.

Disclosure: The author and his law firm work for a variety of private clients in competition matters, including some involving interim measures. This article, however, reflects solely my own independent judgment and was not subject to any form of influence from outside sources.

2 See, for example, OECD’s Background Note on Interim Measures (OECD, 2022) that reports “[c]alls for an increased adoption of interim measures mainly concern[ing] investigations into potential abuses of dominance.”

3 The Brazilian Competition Authority (CADE) has been particularly active in issuing interim measures. From May 2012 to June 2022, CADE’s General Superintendence analyzed 37 (thirty-seven) requests for interim measures involving antitrust investigations of anticompetitive conducts (i.e. excluding interim decisions in merger review). Out of this total, CADE´s GS granted 15 fifteen of them (Mattiuzo 2022, slide 6). Between June and December 15, 2022, CADE’s SG analyzed other 9 requests of interim measures, granting one of them and refusing the others.

4 In Europe, the French Competition Authority, Autorité de la Concurrence, is one of the most active NCAs evaluating requests for interim measures, but it has been cautious in granting such requests. From 2017 to 2022, the FCA ordered two interim measures and rejected around 20 requests (OECD, Note by France 2022, p.3).