Information Exchange among Competitors: The Lay of the Land of Enforcement in Brazil1

By Ana Paula Martinez2 & Mariana Tavares de Araujo3 (Levy & Salomão Advogados)

I. Introduction

Prosecution against hard-core cartels has been an enforcement priority in Brazil for almost two decades. During the five years following the execution of the first leniency agreement and the first dawn raids in 2003, Brazil’s antitrust authorities built a cooperation enforcement network with criminal prosecutors that set the path for the adoption of sophisticated investigative techniques and the imposition of criminal sanctions, including jail sentences, in cartel cases. Following that, CADE concluded the first high profile investigations and spent significant resources on public outreach, which included a comic book for children on the harmful effects of cartels.4

In May 2012, the current antitrust law entered into force and introduced key legal changes, including revised administrative and criminal sanctions to cartel conduct. This marked the beginning of a new phase, ongoing, during which some important enforcement policies are being set and others revised. Price-fixing, bid-rigging and other conduct also treated as hard-core in other jurisdictions remain a priority. At the same time, CADE seems to be to increasingly focusing on pure exchange of information cases, which, in Brazil, are treated as cartels and may also be subject to criminal enforcement.

Sections II and III of this article provide an overview of the relevant rules on cartel enforcement, respectively at the administrative and the criminal levels. Section IV discusses and catalogues the relevant enforcement on exchange of information, and Section V summarizes the key conclusions.

II. Administrative Enforcement

At the administrative level, antitrust law and practice in Brazil is governed by Law 12,529/11, which entered into force on May 29, 2012. The current antitrust law has consolidated the investigative, prosecutorial and adjudicative functions into one independent agency: the Brazilian Antitrust Authority (“CADE”). CADE’s structure includes a Court comprised of six Commissioners and a President; a General Superintendence for Competition (“GS”); and a Department. The GS is the chief investigative body in matters related to anticompetitive practices. CADE’s Tribunal is responsible for adjudicating the cases investigated by the GS – all decisions are final at the administrative level, but subject to judicial review based on both formal and substantive arguments. There are also two independent offices within CADE: CADE’s Legal Services, which represents CADE in court and may render opinions in all cases pending before CADE; and the Federal Prosecution Office, which may also render legal opinions in connection with cases pending before CADE.

Article 36 of Law 12,529/11 sets forth the basic framework for defining anticompetitive conduct in Brazil. It addresses all types of anticompetitive conduct other than mergers. In general terms, the law did not change the definition or the types of anticompetitive conduct that could be prosecuted in Brazil under the previous law, but the new law excluded, from the list of examples of anticompetitive conduct previously contained in Law 8,884/94, the practices of excessive pricing (i.e. the selling of goods or services at an unfair price)5 and unfair price increase. The law prohibits acts “whose purpose or effect is to” (i) limit, restrain or, in any way, adversely affect open competition or free enterprise; (ii) control a relevant market of a certain good or service; (iii) increase profits on a discretionary basis; or (iv) engage in abuse of monopoly power. However, Article 36 specifically excludes the achievement of market control by means of “competitive efficiency” from potential violations.

Under Article 2 of the law, practices that take place outside of Brazilian territory are subject to CADE’s jurisdiction, provided they produce actual or potential effects in Brazil.

The law was broadly drafted to apply to all forms of agreements and exchange of sensitive commercial information, formal and informal, tacit or implied. Cartels, as an administrative offense, may be sanctioned with CADE-imposed fines against the companies that may range from 0.1 to 20 percent of the company’s or group of companies’ pre-tax turnover in the economic sector affected by the conduct, in the year prior to the beginning of the investigation. Officers and directors6 liable for unlawful corporate conduct may be fined an amount ranging from 1 to 20 percent of corporate fines; unlike the previous law, CADE must currently determine fault or negligence by the directors and executives in order to find a violation. Other individuals (that is, employees with no decision-making authority), business associations and other entities that do not engage in commercial activities may be fined from approximately BRL 50,000.00 to BRL 2 billion.7

Apart from fines, CADE may also: (i) order the publication of the decision in a major newspaper, at the wrongdoer’s expense; (ii) debar wrongdoers from participating in public procurement procedures and obtaining funds from public financial institutions for up to five years; (iii) include the wrongdoer’s name in the Brazilian Consumer Protection List; (iv) recommend that tax authorities block the wrongdoer from obtaining tax benefits; (v) recommend that the intellectual property authorities grant compulsory licences on patents held by the wrongdoer; and (vi) prohibit individuals from exercising market activities on his/her behalf or representing companies for five years. As for structural remedies, under the law, CADE may order a corporate spin-off, transfer of control, sale of assets or any measure deemed necessary to cease the detrimental effects associated with the wrongful conduct.

The law also includes a broad provision allowing CADE to impose any “sanctions necessary to terminate harmful anticompetitive effects,” whereby CADE may prohibit or require a specific conduct from the wrongdoer. Given the quasi-criminal nature of the sanctions available to the antitrust authorities, CADE’s wide-ranging enforcement of such provision may prompt judicial appeals.

Companies and individuals will be eligible for full or partial leniency depending on whether the GS was aware of the illegal conduct at issue. If the GS was unaware, the party may be entitled to a waiver from any penalties. If the agency was previously aware of the illegal conduct, the applicable penalty can be reduced by one to two-thirds, depending on the effectiveness of the cooperation and the parties’ good faith in complying with the leniency program’s requirements. Directors and managers of the cooperating firm will be sheltered both from administrative and criminal sanctions if the individuals sign the agreement and comply with the same requirements.

Under the previous law, leniency was not available to a “leader” of the cartel; such requirement was eliminated by Law 12,529/11. Further, a grant of leniency under the previous antitrust law extended to criminal liability under the Federal Economic Crimes Law, but not to other possible crimes under other criminal statutes, such as fraud in public procurement. Law 12,529/11 broadened the leniency grant to extend to these crimes, as well.

Brazil’s Settlement Program for cartel investigations was introduced in 2007, through an amendment to the previous antitrust law. Since March 2013, following the introduction of revised requirements, all defendants in cartel cases must acknowledge participation in the facts under investigation. The provision does not refer to a “confession” and the requirement “to acknowledge participation” may allow for certain flexibility with respect to its terms, compared to a strict “confession” requirement. Also, under the current rules, meaningful cooperation is mandatory in all cartel cases; and the assessment on whether the parties have or not fulfilled the settlement conditions will only take place when CADE issues a final ruling on the case.

In September 2017, CADE republished its Guidelines for Settlement in Cartel Cases to include the detailed chart below ranking the specific weight that will be granted to each aspect of cooperation. The chart comprises a non-binding method for discount calculation, based on a point-system that further detail the weight of each aspect of the cooperation requirement (i.e. documents and information that are evidence of the reported misconduct and cover additional aspect of the conduct reported by leniency applicant are considered more valuable and will lead to greater discount).8

III. Criminal Enforcement

Apart from being an administrative offense, cartel conduct is a crime in Brazil, punishable by criminal fine and imprisonment from two to five years. According to Brazil’s Economic Crimes Law (Law 8,137/90), this penalty may be increased by one-third to one-half if the crime causes serious damage to consumers, is committed by a public servant or relates to a market essential to life or health. Also, Law 8,666/93 specifically targets fraudulent bidding practices, punishable by criminal fine and imprisonment from two to four years. There is no criminal corporate liability for cartel crimes in Brazil.

Brazilian Federal and State Prosecutors are in charge of criminal enforcement in Brazil, and act independently from the administrative authorities. Also, the Police (local or the Federal Police) may start investigations of cartel conduct and report the results of their investigation to the prosecutors, who may or may not file criminal charges against the reported individuals.

Currently, approximately 300 executives face criminal proceeding in Brazil and courts of first instance have decided approximately 20 cases so far. All criminal cases are pending appeal in court. The investigative timeline in criminal cases tends to be longer and less predictable than investigations conducted by CADE.

IV. Relevant Enforcement on Exchange of Information Among Competitors

Brazil’s competition law, similarly to competition laws in most jurisdictions, does not have specific provisions prohibiting exchanges of information. Exchange of information and other facilitating practices have been assessed by Brazilian antitrust authorities under merger review and in connection with anticompetitive conduct investigations, under the statutory provisions on concerted practices. Relevant merger cases include joint ventures and other potentially efficiency enhancing agreements that fulfilled the mandatory filing thresholds. Conduct enforcement mostly looked at industry information sharing systems and at exchange of information within businesses and trade associations.

CADE has reviewed several cases involving coordination among competitors, few of those involving non-cartel horizontal agreements. A reasonable explanation for that could be the fact that Brazilian authorities classify as cartels some cases that might be considered as non-cartel cases in other jurisdictions. CADE’s case law on exchange of information among competitors is an example of that – exchange of commercially-sensitive information has been deemed hard-core conduct, and a cartel violation has been found in the past regardless of evidence of price agreements or market allocation.

Nonetheless, CADE seems to be attempting to differentiate exchange of sensitive information as an independent conduct from those exchanges that are part of the dynamics of the cartel. In September 2016, CADE initiated an investigation, based on a leniency agreement, against 28 auto parts producers and 66 individuals, that allegedly participated in the exchange of commercially and competitively sensitive information that facilitated and potentially enabled the adoption of similar or uniform practices amongst companies active in the aftermarket. The Technical Note that initiated the investigation at times referred to cartel and, at other times, to exchange of sensitive information as a conduct itself. However, in its preliminary decision issued in August 2018, the GS stated that the conduct under investigation is strictly exchange of information, and not a cartel, and acknowledged that the statute of limitations applicable is 5 years. In July 2019, CADE’s Tribunal recognized that even though exchange of commercially-sensitive information may facilitate cartel activity, it is independent conduct.

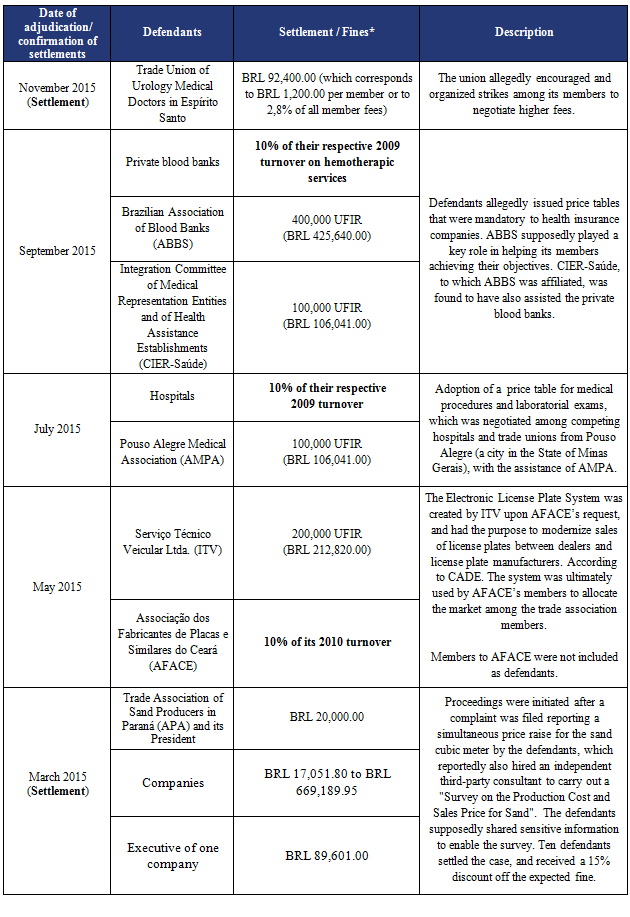

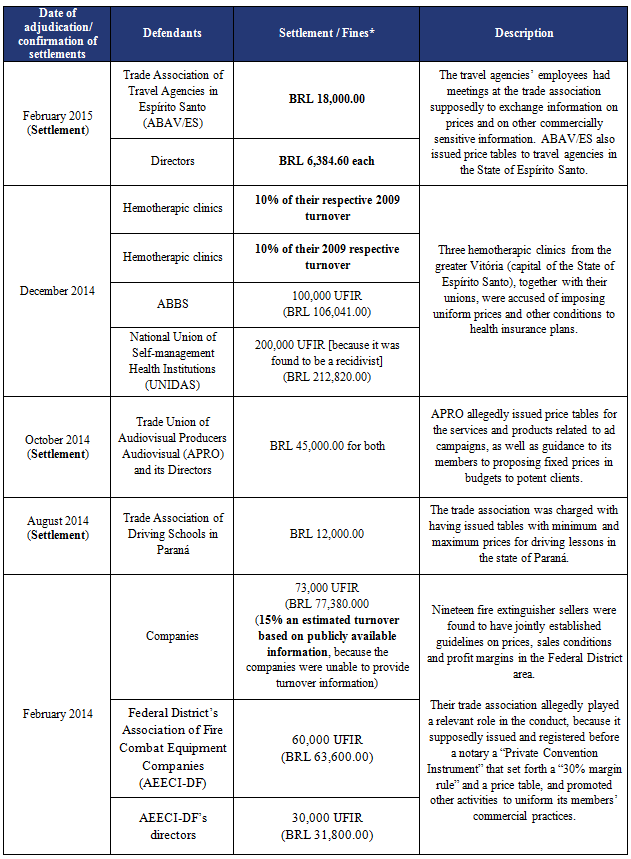

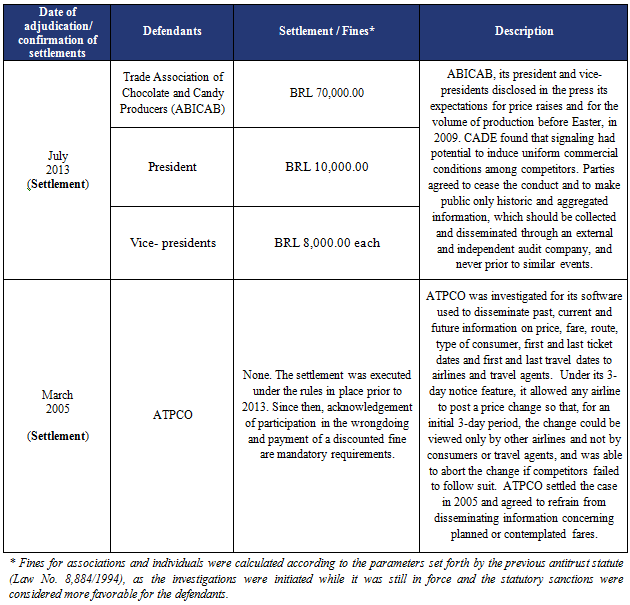

The table below summarizes publicly available information about the key cases in which CADE assessed exchange of information between competitors, including the fines imposed and the criteria adopted to calculate the sum required as a condition for settlement.9

Most of these cases were treated as quasi per se, therefore decisions have not yet assessed potentially pro-competitive arguments11 on sharing information among competitors; and few rulings provide any guidance on the types of information (e.g. aggregated v. disaggregated, current v. future), and the means through which (e.g. black box, independent third party) it would be legal to exchange such data. Exchange of public information amongst competitors has not been considered an infringement of competition rules. At the same time, CADE has defined “publicly available information” narrowly; i.e. information must be readily observable and available to everyone and at no cost. If the information is available to the public but its research and its retrieval are difficult and costly, the information is not genuinely available to the public.

CADE briefly discussed some of these aspects when adjudicating the case targeting Paraná’s Association of Whitewash Producers, which was investigated for preparing a table on minimum production costs, in February 2013. CADE ruled that even though trade associations perform beneficial and even pro-competitive roles, these associations can disseminate relevant commercial information among competitors that can potentially induce their members to adopt tacit or explicit collusive behavior. According to the decision, commercially-sensitive information, including current and future prices; costs and levels of production shared within the associations can lead to anticompetitive effects in the markets, such as facilitating collusion or concerted actions among competitors with respect to prices and other elements (e.g. quantity, quality).

CADE further discussed such criteria when issuing a final ruling in connection with the investigation on the alleged cartel among cement producers in May 2014. CADE found that the relevant trade associations had a key role in implementing the alleged cartel by gathering commercially-sensitive information from cement producers, such as production, consumption and inventory data, and making such information available to their members.12 Under the decision, the trade associations found guilty of collusion were prohibited from (i) collecting data less than 3 months old; (ii) publishing the data before 3 months after having collected it; and (iii) collecting and publishing disaggregated data. CADE emphasized that if the data were to be used for statistical purposes, any entity responsible for gathering the information must exercise care so as to (i) not share the specific information received with third parties, particularly if these third parties are competitors; and (ii) consolidate it in a way it becomes general information and may be made public to any interested party.

Under such rulings, information exchanges of competitively-sensitive information (primarily information on prices, costs, output, capacity, investment plans, and customers) are at a greater risk of being challenged, except if the information is only of historical value, and aggregated in a way that does not permit recipients to identify individual firm data.

Data is generally considered historical from the point on where making it public will not encourage uniform market practices. This varies on a case-by-case basis and there is no clear guidance from CADE on what a satisfactory passage of time would be for specific markets in conduct cases.13 While CADE’s decisions refer to a 6-month time period from the moment when the data was used in the market to when would be acceptable making it public, the same criteria would not necessarily apply to markets where commercial conditions are more stable.

There is limited criminal case law specifically on illegal information exchange between or among competitors, but some cases involving trade associations investigated by CADE also resulted in criminal charges against the relevant individuals. Most of these cases are still pending decision in court.14 On the other hand, in at least two recent cases, the Federal Prosecutors Office recommended to the Criminal Courts that there should not be any criminal prosecution for exchange of information conducts, following the execution of leniency agreements with CADE.

In the case involving driving school and dispatchers referred above,15 the judge at the criminal court of first instance found the individuals involved in the conduct guilty and they were sentenced to serve prison terms of 2 years and 4 months, as well as to the payment of a criminal fine. The prison terms were converted into community services for 2 years and 4 months and the fine was converted into a donation of approximately 10 times the minimum wages to a non-governmental entity. The decision was issued in March 2015.

V. Conclusion

The Brazilian antitrust authorities have lived up to their promise to strengthen enforcement and step up sanctions against cartels since the first leniency agreement was executed and the first dawn raids were conducted in 2003. Changes to the antitrust statute, enforcement action and case law in the last few years indicate that this trend it not about to be reversed. Also, possibly as a response to stricter enforcement, CADE seems to have been expanding its enforcement beyond conduct that is treated as hard-core in most other jurisdictions.

CADE has provided guidance with respect to when information exchanges between and among competitors will be found to be anticompetitive in its rules on gun jumping, when deciding the cases discussed above, and in the 2009 booklet issued by the former Secretariat of Economic Law (“SDE”), on Cartel Enforcement within Unions and Trade Associations.16 These materials are certainly important sources of information, but clear and comprehensive guidance on types and circumstances where CADE will find that such exchanges are anticompetitive (including its views on signaling and benchmarking) is critical and still missing from CADE’s regulatory framework.

A 2010 report issued by the OECD policy roundtables on the information exchanges between and among competitors (“OECD report”)17 lists the following three key factors to assess the legality of information exchange: (i) structure of the affected market, (ii) types of the information exchanged and (iii) the circumstances in which the exchange takes place. After all, not all exchanges are anticompetitive and therefore should be assessed on a case-by-case basis as opposed to other conduct such as price-fixing and market allocation.

Distilling its experience with these cases, CADE could consider setting forth “safe harbors” for exchanges of information taking into account such criteria. Several international precedents provide useful guidance to national authorities and should be considered in order to avoid the business uncertainty that arises when competition rules are applied in an inconsistent manner across different jurisdictions. This would avoid a more stringent treatment by CADE that could disadvantage Brazilian business competing on regional or global markets.

Click here for a PDF version of the article

1 We are grateful to our colleagues Gabriela Forsman, Fernando Hamu, and Isabella Gonçalves of Levy & Salomão Advogados for their helpful input and overall assistance with this article.

2 Ana Paula Martinez is a partner with Levy & Salomão Advogados. Prior to rejoining the firm in 2010, Ms. Martinez served as head of the Antitrust Division and Deputy Secretary of the Secretariat of Economic Law (“SDE”) of Brazil’s Ministry of Justice (2007-2010). From 2008 to 2010, she was the co-head of the cartel sub-group of the International Competition Network. She was a member of Brazil’s Inter-ministerial group of Intellectual Property and the National Strategy for Fighting Cartels and Money Laundering. Admitted to practice in New York and Brazil, she is a member of the ETHIC Intelligence Certification Committee, of the Advisory Board of DRCLAS at Harvard University, Insper, and a member of the Arbitration Chamber of São Paulo’s Stock Exchange (B3). Ms. Martinez holds an LL.M. from USP and Harvard and a Ph.D. in Criminal Law from USP.

3 Mariana Tavares de Araujo is a partner with Levy & Salomão Advogados. Prior to joining the firm, Ms. Araujo worked with the Brazilian government for nine years, four of which she served as head of the government agency in charge of antitrust enforcement and consumer protection policy. Ms. Araujo currently co-chairs the International Bar Association Working Group on International Cartels, is a member of the American Bar Association International Development and Comments Task Force, and a non-governmental advisor to the ICN. Ms. Araujo holds an LL.M. from the Georgetown University Law Center.

4 In celebration of the National Anti-Cartel Day in 2009, the former Secretariat of Economic Law (“SDE”) published The Lemonade Cartel comic book, authored by the most popular comic books writer in Brazil, Mauricio de Souza. Available at http://www.cade.gov.br/acesso-a-informacao/publicacoes-institucionais/documentos-da-antiga-lei/cartel-da-limonada.pdf/view.

5 OECD Competition Committee – Policy Roundtables on Excessive Prices (2011). Available at http://www.oecd.org/competition/abuse/49604207.pdf.

6 Under Article 32 of the law, directors and officers may be held jointly and severally liable with the company for anticompetitive practices perpetrated by the company. Considering the strict sanctions that have been imposed to legal entities by CADE to date, this provision has nearly been forgotten as virtually no individual would be in a position to be held liable for the sanctions imposed against the company.

7 Approximately USD 15,500.00 to USD 500,000,000.00 (exchange rate of USD 1.00 = BRL 4).

8 The English version of the Guidelines for Settlement in Cartel Cases is available at http://www.cade.gov.br/acesso-a-informacao/publicacoes-institucionais/guias_do_Cade/guidelines_tcc-1.pdf.

9 Other recent cases in which CADE specifically discussed the exchange of information, directly or indirectly, among competitors include: (i) Shell/Raízen – in 2014, CADE sanctioned fuel distributor Raízen Combustíveis (formerly Shell Brasil) for trying to coerce gas stations to raise prices and push stations under the Shell brand to collude with competitors. CADE highlighted that the conduct of Shell facilitated access to sensitive information, reducing the costs of a possible coordination between gas stations. The company was fined in BRL 31 million; (ii) ABRINQ – CADE sanctioned toymakers association ABRINQ in 2015 for collusion. ABRINQ held a public meeting in 2006 that was aimed at aligning companies in the industry to sign an agreement on Chinese imports, during which prices, market allocation and new players’ entries were discussed. ABRINQ and its president were sanctioned for inciting collusion through, among other things, the exchange of commercially-sensitive information. Fines were approximately BRL 6,000; (iii) Laundry cartel – in 2016, CADE sanctioned 7 companies and 11 individuals that were involved in a cartel for bid rigging on public procurement for laundry services in public hospitals in 2009 and 2005. CADE found that competitors constantly exchanged commercially-sensitive information, such as commercial strategies and bid values, in order to make the agreement possible. The cartel leader was fined 17 percent of its revenues, while other companies were fined 15 percent. Individuals’ fines varied from 5 to 11 percent of their companies’ sanctions. Other sanctions were also imposed: CADE recommend that the tax authorities block the defendants from obtaining tax benefits and the cartel leader was forbidden from participating from participating in public procurement procedures for 5 years.

10 Exchange rate of USD1 = BRL4,6201as of March 5, 2020, according to Brazil’s Central Bank. Please note that there has been significant volatility of the exchange rates over the past 5 (five) years.

11 CADE’s case law does not provide clear guidance on what would be a strong efficiency defense. In fact, CADE has never allowed an anticompetitive merger to go forward or refrained from sanctioning an anticompetitive conduct on the basis of efficiency arguments.

12 The trade associations were fined in approximately BRL 4 million for their key roles in implementing the cartel, thus, acting beyond their legitimate purposes.

13 CADE’s 2016 Guidelines on Gun Jumping lists as particularly sensitive data: (a) costs; (b) capacity and expansion plans; (c) marketing strategies; (d) pricing; (e) key customers and applicable discounts; (f) employees’ wages; (g) key suppliers and the respective contract terms; (h) non-public information on trademarks and patents and on research and development (R&D); (i) plans for future acquisitions; and (j) competition strategies.

14 Ongoing criminal cases related to CADE’s investigations involving trade associations include Criminal Process No. 2004.71.00.018690-7 (Security Services); Criminal Process No. 0089403-25.2003.8.26.0050 (Crushed Rock); and Criminal Process No. 2003.71.00.007397-5 (Truck Drivers).

15 In the driving schools and dispatchers’ case, which was adjudicated in 2016, the trade association was found guilty of editing price tables, monitoring compliance by the trade association members and calling meetings to discuss such tables. The trade association allegedly hired an IT company, Criar, to develop software that, in CADE’s view, promoted uniform conduct of competing driving schools and dispatchers by consolidating information on prices of packages of classes and clients. CADE imposed fines to companies ranging from BRL 7,000 to BRL 122,000. The trade association was fined in BRL 146,845.80, and the IT company Criar in BRL 392,718.38.

16 Available at http://www.cade.gov.br/acesso-a-informacao/publicacoes-institucionais/documentos-da-antiga-lei/cartilha_sindicatos.pdf/view.

17 See “Information Exchanges Between Competitors Under Competition Law, 2010,” available at http://www.oecd.org/competition/cartels/48379006.pdf.