By Eleanor M. Fox1

Negotiations are on a fast track for a competition protocol for the African continent. What should be the design? This is a moment of opportunity. Most African nations have a competition law, but with competition authorities at various stages of functionality. Africa has eight Regional Economic Communities recognized by the African Union, but these are also at varying stages of functionality. Should the competition policy for the continent simply be a forum for cooperation of the existing communities and nations, nudging development of the laws and cohesion? Or should it be much more ambitious, putting Africa at the world competition table, poised to take a stand on megamergers and world cartels that hurt Africa? This essay urges the latter, but also urges, in order for Africa to have an authoritative voice, the competition powers at the center must be slim and focused.

I. Introduction

A competition law for Africa is on a very fast track. The Agreement Establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area entered into force on 30 May 2019 after 54 of the 55 members of the African Union – all but Eritrea — signed the document, and trading under AfCFTA began in January 2021. The agreement specifies that a competition protocol is to be negotiated and will form an integral part of the Agreement. Drafters of the competition protocol are targeting November 2022 for submitting the document to the Council of Ministers.

This is a moment of opportunity for Africa. The continent is not well integrated and is rife with restraints on trade and competition. Intra-African trade accounts for only about 16% of African trade,2 while in other regions, such as North America and Western Europe, about half the trade is intra-regional trade. Significant improvement in economic integration of African countries would almost surely decrease the cost of goods and services including those most essential to the poor populations, alleviate the growing crises of poverty, and open the doors of economic opportunity to billions of aspiring entrepreneurs who have been left out of the economic system.

What vision for the Competition Protocol for Africa? The possibilities stimulate the mind; the occasion provides an intellectual feast for architects of institutions, with immense practical implications. What would the best design for Africa look like? Should it be a network of the competition families of the African nations (those that have and will have competition laws), sharing information, giving mutual support, working towards best principles, and avoiding conflicts? Should it be such a network of the Regional Economic Communities of Africa? Should it be a full-fledged competition law such as in the European Union or various African nations? Should it be something new, bespoke for Africa?

The answer could either put Africa on the map as an important player in the competition law/policy community, standing up for the second largest and second most populous continent on earth, or could foretell a largely dispensable piece of paper.

To answer the question – what design? –it is useful to ask two questions, each of a different sort: 1) What range of possible designs does experience suggest? And 2) Looking back, what are the missed opportunities of an Africa with no competition function at the center?

This essay first addresses the two questions. Based on the answers, it selects an architecture, which is not a clone of a “best standards” full competition law adopted by nations but is a bespoke structure focused on a narrowly-honed enforcement agenda, taking on a policy role in priority pan-African issues, a role in coordinating regional economic communities and national competition authorities, a mandate to coordinate tightly with the free movement directorate of AfCFTA on cross-border restraints, and a world-community-facing role as voice of Africa, which would place Africa at the table when the next global megamerger or world cartel appears on the horizon. The essay then elaborates on how the bespoke architecture could work on key issues, such as scope and devolution of authority.

II. The Foundational Questions

A. What range of designs does experience suggest?

Here are six concepts, which could be models or referents, alternative or complementary:

- Purely horizontal coordination of competition authorities of various nations or regions.3 The coordination could include technical assistance and capacity building. It could include work towards model standards or practices, as a part of soft convergence. It could include a variety of experience-sharing projects. The International Competition Network (ICN) and the African Competition Forum (ACF) fit this description.

- A full traditional competition law, cut, pasted, and selectively adapted, complemented by institutional provisions drawn from the African or other Regional Economic Communities.

- Experience may be drawn from competition clauses in free trade area agreements. These provisions typically state: Members must have and enforce competition laws. Recent agreements add: and the members must enforce these laws with due process. Dispute resolution is typically not available.

- The European Union provides the most integrated model, and while Africa does not aspire to the degree of European integration, some of the European experiences and formulations may provide useful lessons. Designed to create a common market (for peace in Europe), the EU has a complete competition law at the center. The competition law prohibits both private and State anticompetitive restraints. Antitrust is integrated with prohibitions of State restraints on free movement of goods and services. EU has a system for mergers of community dimension; for these mergers, the EU has exclusive jurisdiction within the Union. Moreover, the EU has adopted the subsidiarity principle: What can be done as well or better at a lower lever should be done at the lower level (although the EU does not apply the principle as robustly as it could). Having at first taken on more functions than it could efficiently handle in vetting all agreements that may distort competition, the EU shifted course. It ceased vetting and exempting agreements and devolved powers to the Member States – a move of subsidiarity. Finally, the EU has established a network of Member States, the European Competition Network (or “ECN”), through which the Member States coordinate on the handling of cases. In cases with cross-border effects but not of European Community dimension, the best-placed Member State handles the case.

- Lessons may be drawn also from aspects of the institutional design of US antitrust that give power to the states. In competition matters, the US States and the Federal Government share authority. They have concurrent jurisdiction. In case of conflict, the federal law applies; but “conflict” is narrowly construed and conflicts of a dimension that would displace state authority almost never happen, even in the case of mergers where the state is more aggressive than the federal government in finding anticompetitive effects. As in the EU, the state and central systems are mutually supportive and mutually enriching, and the state authorities command easier recognition of norms (e.g., cartels are wrong) as a result of federal policy and enforcement.

- Finally, important lessons may be drawn from a particular plurilateral trade agreement within the context of the World Trade Organization in the telecommunications sector. In 1997, 69 members of the WTO adopted the Telecommunications Agreement, and 61 of these signed a Reference Paper with an antitrust protocol. Under the antitrust protocol, all signatories to the Reference Paper agreed to maintain competition laws and their enforcement. The parties’ commitments were subject to dispute resolution. Mexico was a signatory. The Mexican Telecoms regulator issued regulations that essentially ordered a cartel of the Mexican telecoms firms that received transmission of out-of-country calls into Mexico. It required all such firms to align their prices to that of the market leader, Telmex (which was owned by Carlos Slim, a great donor to the President). AT&T complained to the US about the monopoly price of calls to Mexico, and the US brought proceedings before the WTO. The WTO panel agreed with the United States. It held that Mexico could not evade its obligation to prevent cartels by ordering them.4 While this is just one panel holding on a large sea, the Mexican Telecoms case crafts a trade-and-competition tool fit to attack public/private cross-border restraints that undermine market integration. Mexican Telecoms unwittingly anticipated one of the biggest economic problems of Africa.

B. Looking backwards: What has Africa missed? What is Africa missing?

The second background exercise is to look backwards and consider what might have been if competition law had been in place at the center. With this knowledge, we can be sure to construct the missing pieces into the AfCFTA competition protocol.

There are four points as to which Africa has been missing out and where its presence could have made a substantial difference to the wellbeing of its people: 1) megamergers, 2) global cartels, 3) below-the-radar cross-border restraints (often hybrid public/private, combining privilege and power, as in Mexican Telecoms), and 4) a voice and face of Africa at the world competition table to champion Africa’s position when the global restraints arise.

Megamerger examples include Holcim/Lafarge (cement) and Bayer/Monsanto (seeds, chemicals for agriculture). These megamergers had the potential for significant anticompetitive aspects, especially in Africa.5 The Holcim/Lafarge transaction joined the two leading firms in an industry rife with cartels in almost every jurisdiction in the world; cement is one of the two most notorious industries (along with sugar) of cartel recidivists. In the case of these mergers, the US, the EU, and other major jurisdictions in the world ordered spinoffs and conditions to protect their own citizens and threw the problem to African nations to do what they could to protect themselves.6 Had there been a Commissioner for Competition for Africa to sit at the “world table” with the EU, US, and others from day one to vet the merger and to share the anticompetitive harms as well as to scrutinize the firms’ claims of benefits, Africa and each other major jurisdiction may well have prohibited the merger.

A similar scenario is easily envisioned in the world cartel cases. Recent world cartels include air cargo, car parts, freight-forwarding, and vitamins. The developed country jurisdictions prosecuted the cartels and their injured citizens got recompense. Presumably, no person victimized in Africa got recompense; and while some African nations penalized the cartels, the fines were minuscule compared to the cartel gains. Cartelizing Africa will continue to pay until Africa singles out the perpetrators, punishes them with fines if not jail or professional disqualification, and recoups the gains, in amounts so large or punishment so weighty that African-facing cartels will not pay.

Big Tech and its abuses similarly pose problems around the world. There is a developing narrative as to how Africa is hurt by the abuses and how it can be helped by curtailing them.7 But there is no all-African platform to tell the African story to the world and to help the Continent form a consortium to tame the abuses.8

Finally, there is a major problem of cross-border restraints that are not yet fully discovered, let alone remedied. In significant ways in significant industries, trade does not flow across borders as the observer would expect. Researchers are cataloguing suspicious circumstances.9 The obstructions may be cartels or hybrid public/private restraints, or they may be the result of bribes or corruption or “merely” the privilege of entrenched interests and cronies. Africa is Balkanized, surely in part a legacy of colonialism, where the colonizers extracted minerals and carved out trade routes to their own countries. If Africa is to be integrated, and if competition policy is to help, Africa must get to the root of the problem and eradicate the border barriers erected by the vested interests, the cartelists, and the co-opted or opportunist State. 10

In sum, these are the four touchstones that illuminate what Africa, in the absence of a competition policy, has been missing the most: a major merger chief, a major cartel chief, a trade-and-competition function, and a voice for Africa.

III. The Design; The Principles

The design should be a function of four simple principles.

- Do what is necessary; do what is important for Africa and what no other institution will or can do.

- Do not “bite off more than you can chew.” Limit scope.

- Simplify the legal prohibitions. Do not overcomplicate. Do not use ambiguous words. Focus on making Africa economically strong and competitive and making its markets accessible.

- Nurture; do not preempt. The center should use all the help it can get from well-functioning entities in the ecosphere.

A. Do the necessary

- Be ready for the “tip-of-the-iceberg” enforcement. When the next African-harming megamerger is proposed, be there at the world table. Assemble the best “lean and mean” team by deputizing the best merger lawyers in Africa, ready to litigate. Similarly for world or pan-African cartels.

- Take on the “tip-of-the-iceberg” conversation and brainstorming of the other great competition problems faced by Africa and the world, such as how to control BigTech/Big Data, and competition-relevant problems of pharma, agriculture, food security, and value chains.

- Collaborate tightly with the free movement directorate of AfCFTA; uncover below-the-radar conduct that keeps Africa unintegrated, and enforce against it.

- Play the role of institutional development, nurturing and coordinating among the multi-speed levels of the scaffolding – regional, national, and grassroots, through a new African Competition Network that works with and learns from the ACF. Devolve (leave) to regional communities the day-to-day tasks of technical assistance and capacity building of national agencies, and fleshing out the regional systems.

B. Limit the scope

Streamline jurisdiction, so the center takes only the most continent-relevant cases. This would probably mean only a handful of merger cases and a handful of cartel cases a year in early stages. Scope can be expanded later in response to developing capabilities and challenges, and as the free trade area transforms into a common market. Lessons can be drawn from both COMESA and the European Union in formulating thresholds that limit the reach of the center.

While the reach of the center should be seriously limited, this does not mean that member states and regional authorities must be precluded from local measures dictated by their markets and concerns. If a megamerger is enjoined at the center, there would be nothing left to do. But if the merger is cleared or cleared subject to spinoffs, a member state need not be precluded from local relief to protect competition or, for example, workers. Concurrent jurisdiction is usually fine, guided by a prohibition of beggar-thy-neighbor restraints that undermine the FTA or common market such as export cartels from one member state into another. The concurrent antitrust jurisdiction of US states and the federal government is a good example of an institutional system that works well. So too is the relationship of EU and its Member States in non-merger cases, allowing Member States more flexibility than the center to condemn abuses of dominance.

Streamline functions. The center should not become the central vetter of mergers for Africa. We will know when the next Holcim/Lafarge deal comes along; a typical broad pre-merger notification scheme is neither necessary nor desirable. Nor should the center become the central vetter of agreements, opining on “exemptions” for agreements that might not even harm competition. A file-and-exempt scheme is unnecessarily regulatory. Pre-agreement/pre-merger notification with clearance responsibilities would strangle the young system.

C. Simplify the law

Substantive competition law has become too complicated, even for developed jurisdictions. Statutory wordiness is a handicap that tends to separate law from its roots. Long statements of categories, and burdens of proof specified for each category, ossify the law, prolonging administrative proceedings and litigation, unduly widening discretionary space, and wasting billions of euros or their equivalent. Attention should be paid to the Preamble of the Agreement establishing the AfCFTA, which specifies “the need to establish clear, transparent, predictable and mutually-advantageous rules to govern Trade … [and] Competition Policy ….”

The substantive law can be simply stated:

1) no hard-core cartels,

2) no agreements that are anticompetitive on balance after accounting for efficiency and innovation aspects,

3) no anticompetitive mergers – importing the same qualifier, and

4) no abuse of dominance or of substantial market power.

These categories are meaningful. Attempting to spell them out with pages for each category usually does not clarify and drags the discussion into endless debate on ambiguous terms. For anchoring the law, a list of the four prohibitions can be accompanied by advice to draw from an established body of law such as EU law.

Proscriptions (and prescriptions) should be based on the anticompetitive quality of the acts or transactions, and not supplemented with unfairness and industrial policy. Unfairness jurisdiction and industrial policy —so important to the nations — should be left to the member states or regionals. Industrial policy in the sense of what is good for all of Africa, such as the environment for the continent, might be available to the center.

The key is: clear, simple law with streamlined scope for jurisdiction and built-in restraint of the center to leave to the regionals and nationals restraints without a significant pan-African dimension.

D. Nurture

The center has a nurturing role. It is the central player at the tip of the pyramid, with heavy lifting below and key issues and projects rising to the top. It should recognize and use to the fullest extent it can the immensely positive capabilities of the several well-functioning national agencies and regional communities, coordinate with the work of the African Competition Forum, and coordinate with research institutions such as CCRED of the University of Johannesburg on cross-border restraints. It should build mutually reinforcing links throughout the pyramid, with feedback up and down.

IV. What Will Be Success?

Africa has a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. If the right blueprint is put into place, it can make a real positive difference to the lives of Africans. If an unfocused, unambitious, or overly ambitious program is adopted, the protocol will do little significant work and the inflection moment will be lost.

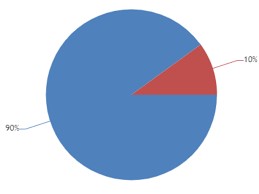

Think of a pie chart, and think five or 10 years out. How would you like to see the African Competition Commission spending its energies and resources?

Consider these five functions that can be ascribed to the competition protocol: 1) world-facing leadership, with Africa at the table; 2) selective enforcement against the most serious and wide-spread pan-African restraints; 3) nurture and leadership in coordinating with regionals, national authorities and the ACF and building up the scaffolding; coordinating tightly with the AfCFTA free movement directorate; researching the economic facts that go to the heart of integrating Africa; 4) vetting and clearing mergers, 5) vetting and clearing agreements.

If, at the end of the five years or ten years, tasks (4) and (5) fill 90% of the pie chart, the mission has failed.

If tasks (1), (2) and (3) fill 90% of the pie chart, that will be success.

Click here for a PDF version of the article

1 Eleanor Fox is Professor Emerita, New York University School of Law. She thanks Vellah Kedogo Kigwiru and Willard Mwemba for their very helpful comments.

2 See The African Continental Free Trade Area: A tralac guide, 8th ed. March 2022.

3 See Vellah Kedogo Kigwiru, Supranational or Confederate? Rethinking the AfCFTA Competition Protocol Intitutional Design (April 2022), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4055877.

4 Eleanor Fox, The WTO’s First Antitrust Case – Mexican Telecom: A Sleeping Victory for Trade and Competition, 9 J. Int’l Econ. Law 271 ( 2006), https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgl012.

5 See, e.g., as to Bayer/Monsanto, Ioannis Lianos and Dmitry Katalevsky, Economic Concentration and the Food Value Chain, Legal and Economic Perspectives, in Global Food Value Chains and Competition Law, I. Lianos, A. Ivanov and D. Davis, eds., 2022, Chapter 6, esp. pp 152-158; as to the Holcim/Lafarge cement merger, see Surbhi and Sandeep Vij, Post-Merger Integration Challenges in Lafarge-Holcim Merger, 11 Pacific Bus. Rev. Int’l 62 (2019).

6 See Eleanor Fox and Mor Bakhoum, Making Markets Work for Africa 75, 136-139 (2019).

7 See Thembalethu Buthelezi and James Hodge, Competition policy in the digital economy: a developing country perspective, 15 Comp. L. Int’l 201 (2019); Provisional Report on Online Intermediation Platforms, Market Inquiry, South Africa Competition Commission, July 2022, https://www.compcom.co.za/online-intermediation-platforms-market-inquiry-provisional-report/.

8 Competition enforcers in five African countries – Egypt, Kenya, Mauritius, Nigeria and South Africa – have formed a consortium to examine the digital economy, with a focus on barriers to entry and harmful mergers. See Olivia Rafferty, Enforcers in developing countries monitoring EU efforts to regulate Big Tech, Global Competition Review, 23 Sept. 2022. This helpful development and may augur a future for smaller groups of like-minded countries to pursue common ends.

9 See African Market Observatory Team, CCRED, University of Johannesburg, https://www.competition.org.za/africanmarketobservatory. See also Nsomba, G., Roberts, S., Tshabalala, N. and Manjengwa, E., Assessing agriculture & food markets in Eastern and Southern Africa: an agenda for regional competition enforcement 2022 working papers, https://www.competition.org.za/working-papers.

10 See E. Fox, Integrating Africa by Competition and Market Policy, 60 Rev. Indus. Org. 305 (2022).