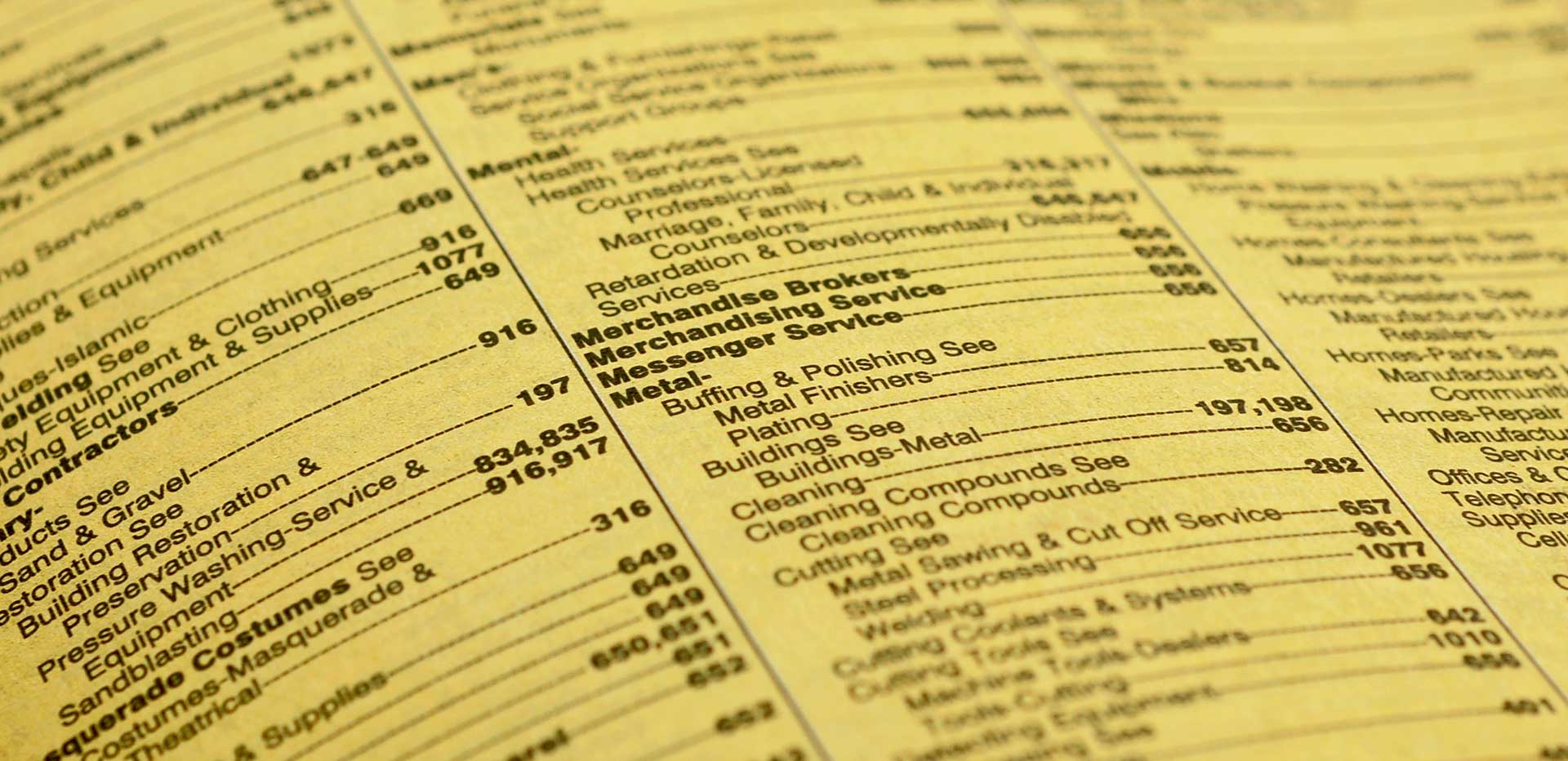

Over the last three decades, the search process for commercial information has changed fundamentally. The move from yellow pages to search engines has been accompanied by fundamental changes in the advertising model. These changes are argued to arise from three main differences between media technologies: content “depth,” display space, and cost structure. The printed yellow pages are unconstrained in paper space, as new pages are easily added, so pricing was based on the size of the ad. Search engines have a different problem, to allocate scarce space on a screen to its best use. A scarcity premium is paid by each successful advertiser, as determined by auction. But the number of advertisers from whom surplus can be extracted from a single search is low. Although auctions by click price expand opportunities for advertisers who could not cover the price of printed ads, the aggregate effect of the move to search engines must account for screen scarcity, content detail and the ability to extract higher value from higher value ads.

By Sean F. Ennis[1]

The medium is the message.

-Marshall McCluhan

I. INTRODUCTION

Over the last three decades, search engines have largely replaced yellow pages as sources of information on commercial sellers. This gradual change for users heralded a dramatic change in business model despite the consistency of media technologies being two-sided platforms. Counter-intuitively, this change reduced the information available in th

...THIS ARTICLE IS NOT AVAILABLE FOR IP ADDRESS 216.73.216.116

Please verify email or join us

to access premium content!