By Timothy Cowen (Preiskel & Co LLP)1

Summary

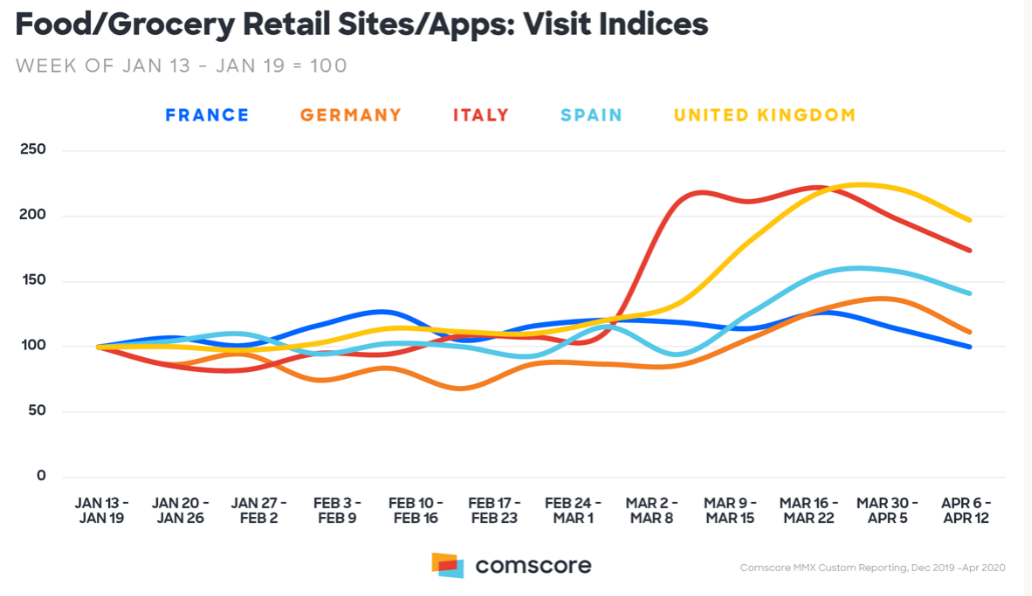

The CMA has reported record numbers of complaints about business behavior since the pandemic and associated lockdown measures hit the UK.2 Unjustifiable price increases have included price rises for essential goods, with the largest price increases reported relating to hand sanitizer, with a median price now approaching 400 percent. The chart below is from the CMA release of May 21, 2020:

The pandemic has shown how quickly shocks to “efficient” supply chains can create shortages. In March 2020, there were widespread reports of empty supermarket shelves and certain products remain elusive, such as flour in consumer-retail size bags.3 It has also shown how specialized supply chains struggle to pivot to new markets, with reports of millions of pints of milk being poured away as suppliers struggled to switch from commercial supply to consumer retail.4

The CMA struggles to bring cases under competition law to address short term price rises. Such price rises could be exploitative and illegal abuse – but are only illegal under competition law in the UK if conducted by dominant players. Unlike many states in the U.S. there may be a gap in the UK armory for protecting consumers – arguably, no current law exists to stop players from cornering the market and raising price in the short term. We have no UK law to specifically prevent price gouging. Which? The consumer organization, continues to raise the issue – pointing to the fact that the most vulnerable are facing an inability to shop around physically, and price rises online are significant.5

The UK Government is now looking at changing the law. Increased powers are probably needed. What those could be is discussed after a review of specific examples.

Shocks to Supply Chains

Shortages and price rises have arisen due to (i) demand side shifts to different suppliers and supply chains, along with different purchasing patterns; and (ii) supply side rigidity, where established relationships or contracts are relied upon which can either boost particular suppliers, such as Amazon, or prevent suppliers switching to follow demand, such as commercial milk suppliers being able to switch to sell their products in retail outlets.

The most visibly affected sectors have been travel, retail, and the hospitality sector, where demand has collapsed. Consumer fear, reduced spending, and government restrictions also serve to further reduce or limit demand. Meanwhile, some may be profiteering, by restricting output to raise prices above those that would apply in competitive markets, and extract a high profit from those most in need

This is especially problematic where Government controls limit people’s ability to shop around. As a result local competition, which was more intense in normal times involving larger numbers of suppliers competing across bigger catchment areas – has now been restricted. The government restraints may thus limit the competition between suppliers that would have kept prices in check.

The UK’s CMA has made a considerable effort to get complainants to inform it of unfair practices. The CMA’s Lord Tyrie, has said: ‘We will do whatever we can to act against rip-offs and misleading claims. Where we can’t act, we’ll advise government on further steps they could take if necessary.’6 Profiteering has been condemned in parliament.7

We consider below two case studies: supermarkets and online sales.

Supermarkets

It has been estimated that an extra £2 billion was spent in supermarkets in March 2020.8 While many claimed stockpiling was occurring, Kantar has estimated that only 3 percent of shoppers were stockpiling.9 Instead, in reality, a switch from restaurants, cafes and sandwich shops to supermarkets saw increased demand outstrip supermarket supply.10

At the same time, the cancelling of discounts or offers, and price rises have been reported,11 potentially indicative of prices rising above competitive levels, where suppliers have been restricting output i.e. profiteering.

Price increases likely reflect reduced ability to shop around. Supermarket competition is dependent on catchment areas, and COVID-19 restrictions meant smaller catchment areas apply with less competition taking place; a shift from normal to abnormal conditions of competition, with attendant price increases.

Food distribution in the UK is often bifurcated between supermarket and restaurant channels.12 When the pandemic hit in March 2020. restaurant suppliers were unable to quickly pivot to address supermarket demand. Moreover, supply lines to supermarkets are based on a system of just-in-time delivery, which was not flexible enough to meet the changes as demand shifted from restaurants, causing empty shelves.

The CMA acted to allow supermarkets to coordinate in order to ensure supplies reached the market13 In the short term, this should help ensure stock customers. However, it may also lead to price increases creeping in and may limit the competitive response among supermarkets which should otherwise keep prices in check.

Also, the pandemic may have revealed a deficient UK market structure, lacking in alternative capacity and resilience. In turn, this raises difficult questions about the UK’s food security in the longer term; and whether action is now needed to address the structure of supply and increase longer term supply chain resilience.

Under current competition laws, unfair and exploitative pricing is illegal but dominance or market power first has to be proved. This may be challenging and difficult to assess within a short time frame. The CMA has conducted many investigations of UK supermarkets and, as a consequence of blocking deals14 and forcing divestitures of stores, the UK had an arguably competitive market prior to the Lockdown. Whether that is now the case has not been examined, and perhaps should be. Local markets are now constrained and the extent to which prices have risen on a regional or local basis needs to be investigated. The UK’s Market Investigation regime would be appropriate and solutions to supply chain resilience can be addressed under the remedies already available in that law.

Online Sales

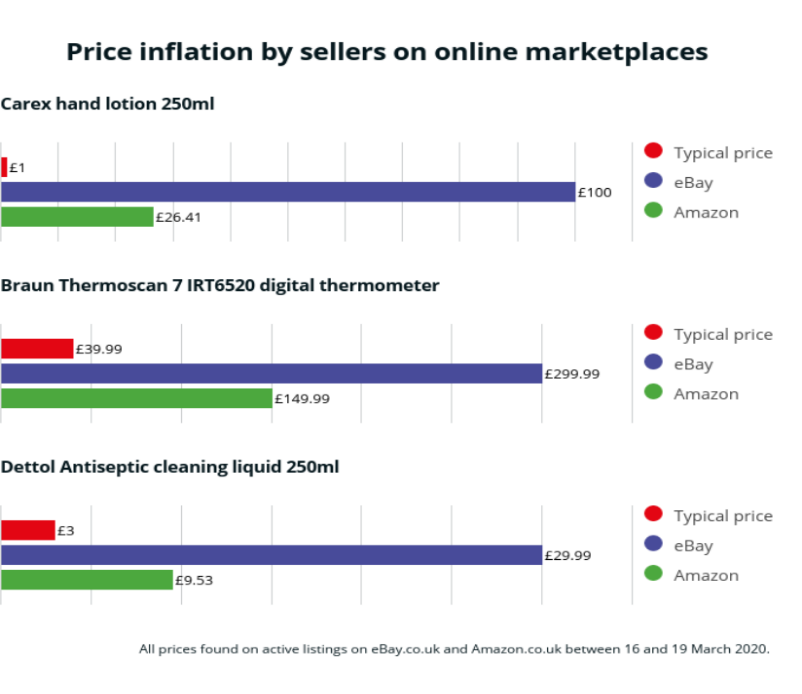

Data from Comscore below suggests the pandemic has accelerated a shift to on line sales:

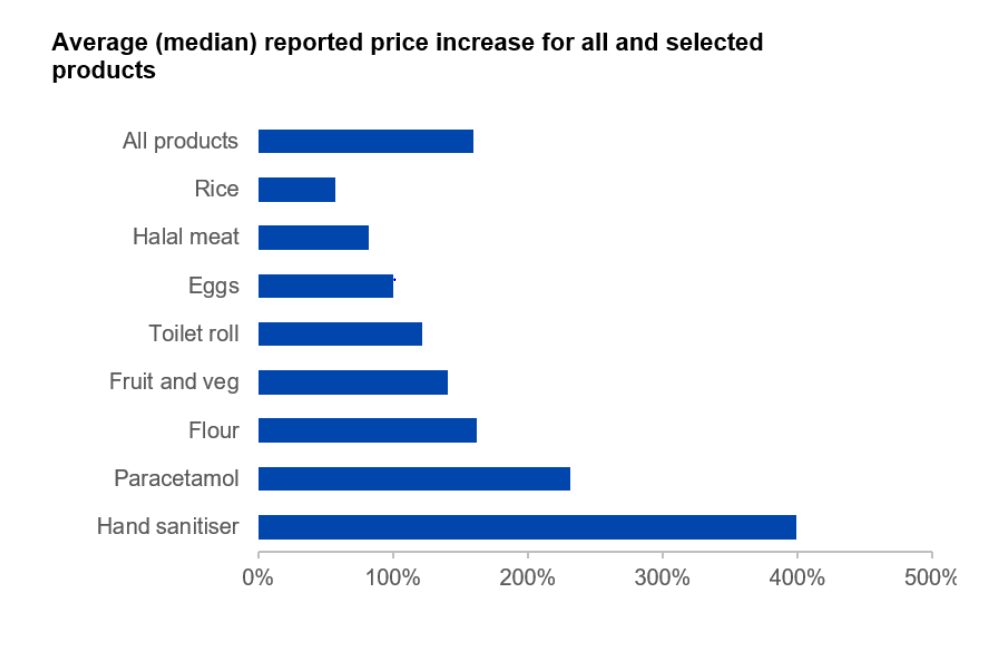

However, Which?, the consumer organization, has found items in high demand or scarce in supermarkets have been for sale online at significantly inflated prices, some with mark-ups of 1,000 percent.16

Amazon has pledged that “price gouging has no place in our stores.”17 However, Which? found that, in particular, items such as thermometers, anti-bacterial hand sanitizer, and cleaning liquids were found online for hugely inflated prices:

Online platforms’ unsurpassed home delivery services are a vital resource for many in lockdown. They have become a modern utility. However, not all practices are likely to be deemed acceptable- with contract clauses and market practices that limit competition between online outlets now the subject to class action litigation in the U.S.19

Moreover, the shift to online platforms is likely to affect longer-term behavior and the longer term structure of supply and distribution of many products, both online and offline.20

This is likely to enhance the market power of online platforms both vis-à-vis consumers, and vis-à-vis suppliers. The medium to long term effects of pandemic may also be that people have formed new habits, further affecting market structure, weakening supply chain competition and affecting prices in the longer term.21

The Current Legal Framework: Unfair Pricing and Profiteering

The CMA has reported that it has received almost 21,000 complaints in relation to businesses’ behavior during the pandemic.22 A substantial proportion concern unjustifiable price increases, particularly for essential goods.”

The CMA could seek to take cases under current law. It could be argued that price increases, even over a short time period, are abuses of short-term dominance. The European Court has made such findings in the past, where suppliers increased prices in times of shortages.23 However, the precedents are old and the CMA may be unwilling to take such cases as they would be practically difficult to from the practical for fear of losing and then setting unwelcome new precedent.24

Moreover, which prices increases constitute abuse, and which are legitimate responses to the economic disruption and market changes caused by the pandemic, may be difficult to establish as a matter of fact. Retailers may have cancelled volume related incentives due to shortages and may be in effect be increasing prices per item. However, retailers may also have a defense, those price rises may be needed to cover increased costs due to the pandemic, such as increased employment and more people being needed to operate in a new social distancing mode, increased numbers in rotas, or increased cost for providing protective equipment to staff. It would be for the retailers to prove that such cost increases justified the level of any price rises implemented.

Benchmarking against competitive pricing levels may help to establish whether profiteering is taking place. This exercise is likely to be straightforward, as a reference time period is available between pre-pandemic pricing and pandemic pricing; prices up to around the end of February 2020 in the UK, and prices thereafter.

The Court of Appeal has very recently considered the test for unfair pricing in UK and EU competition law and the nature of evidence required in CMA v. Flynn and Pfizer.25 The case was directly concerned with abusive pricing. The court considered: (i) the level of prices and profits that abuser charges; and (ii) the evidence needed to determine when prices and profits are unfair or excessive. Each is addressed further below.

- Fairness and Economic Tests

In broad terms, a set price breaches competition law when the dominant undertaking has reaped trading benefits which it could not have obtained in conditions of “normal and sufficiently effective competition,” i.e. “workable” competition.26 The courts have long held that a price is “excessive” because it bears no “reasonable” relation to the economic value of the good or service in question.

The Court of Appeal Held that there is no single way in which exploitative abuse might be established.; On a case by case basis, a competition authority might use more than one of the economic tests available. Common methodologies include: (i) cost-plus tests to determine profit margins27; (ii) analysis of whether profit margins are excessive through benchmark tests such as return on sales or return on capital employed28; and (iii) where pricing exceeds the relevant benchmark test, comparison may be made with price charged against other factors which might justify pricing levels. Importantly, there is no fixed list of categories of evidence relevant to unfairness.

- Evidence

The Court Of Appeal found that the CMA has wide discretion in determining which evidence to rely on. How it goes about evaluating evidence will be fact and context specific.29 However, the Court of Appeal did note that while “if a competition authority chooses one method (e.g. Cost-Plus) and one body of evidence and the defendant undertaking does not adduce other methods or evidence, the competition authority may proceed to a conclusion upon the basis of that method and evidence alone,” but , “If an undertaking relies, in its defence, upon other methods or types of evidence to that relied upon by the competition authority then the authority must fairly evaluate it.”30

The law thus provides flexibility and entitles the defendant to put forward context specific evidence to justify their actions, for example in relation to short term cost increases, as outlined briefly above.31

Solutions: Price gouging and supply chain resilience.

Price controls would be one way of addressing price gouging. Historically, price controls were applied in the UK times of shortage caused by war.32 They worked on the basis of a benchmark price level, from before the onset of war (or in current times, pandemic), against which prices were set. The Second World War, price controls involved maximum price caps imposed on the prices of a long list of raw materials, foodstuffs, and fuels. Prices were set in relation to the prevailing prices at 21 August 1939, with an adjustment or permitted increase over time.

One of the main aims was the restriction of profits to a “reasonable” level by reference to the pre-war benchmark. Unfairly profiting from the emergency was regarded as contrary to the public interest.

However, inspiration can also be drawn from modern laws that address the issue of price rises in emergencies. The UK is one of the rare countries in the world not to have specific laws that govern price rises at times of emergency. The US has frequent emergencies and natural disasters and many states have laws33 that automatically prevent price rises whenever an emergency is declared – for example California automatically outlaws price rises beyond 10 percent from the date of the declaration of a public emergency.34

According to economic theory objections can be raised against to anti-price gouging laws. It is argued that such laws prevent the price signalling that happens when price rises attract suppliers to divert capacity to meet the increased demand. In turn, those who value the good the most will be willing to pay a higher price than those who do not value the good as much. The issue with this type of argument is that it is typically the richest or least price sensitive that are exploited – the rich may be willing to pay a higher price raising the prices of all similar products beyond the reach of those with less disposable income. When it is also realised that very vulnerable people are unable to shop around and lockdown rules effectively require them to become dependent on online sales, it can perhaps be appreciated that the ability to raise prices, for example for essentials such as healthcare products and foodstuffs at time of pandemic is exploitative of those who are more vulnerable physically ( being less able to shop around) or economically (in being poorer).

Communities are affected, and prices are rising. Recession is looming, and people are highly vulnerable given the risks to employment and income, whether they have been supported by government intervention or otherwise. Ignoring the language of economics, it can be said that price gouging exploits the weak and the poor. Laws against price gouging, modelled on laws such as those in California, could be introduced in the UK.

New laws to address supply chain resilience?

The pandemic has exposed the fact that businesses have not ensuring alternative sources of supply in circumstances of pandemic – where cross supply chain failure occurs. No new laws are needed to ensure that supply chain resilience is assured. Current competition law could be more effectively enforced against the objective that alternative productive capacity needs to be available in times of pandemic. For example, in pandemic, Force Majeure clauses could kick in; allowing suppliers to switch and change their arrangements to meet changes in demand. No doubt current contracts may not have addressed the eventuality of pandemic, but the CMA has power in the Market Investigation regime to impose changes to contracts.

The system has allowed supply chains to evolve into their current structure over time. Reversing the decline of supply chain resilience, and increasing the available capacity in the system, is likely to require a change of outlook and a reorientation of the objectives of competition policy. The law in the UK requires the promotion of competition. It could be applied- under the UK’s Market Investigation regime, to secure competitive and resilient outcomes. That could be achieved if the “promotion of competition” objective were looked at from a supply side perspective – supply side capacity needs to be assured if supply side responses are to address increased demand, at times of emergencies.

Click here for a PDF version of the article

1 Chair, Antitrust Practice Preiskel & Co LLP.

2 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/protecting-consumers-during-the-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic-update-on-the-work-of-the-cmas-taskforce/protecting-consumers-during-the-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic-update-on-the-work-of-the-cmas-taskforce.

3 https://metro.co.uk/2020/05/21/why-still-there-shortage-flour-12736838/.

4 https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/coronavirus-dairy-milk-farmers-throw-away-shortage-lockdown-a9457001.html.

5 See the Bunker “Cashing in on Coronavirus” interview with Adam French at Which? @bunker_pod.

6 “COVID-19: sales and pricing practices during Coronavirus outbreak”, CMA March 5, 2020.

7 https://edm.parliament.uk/early-day-motion/56912/price-gouging.

8 https://inews.co.uk/news/consumer/coronavirus-uk-supermarket-visits-shopping-figures-covid-19-spending-lockdown-2523680.

9 Chris Morley, “Why stockpiling is not the crazy, selfish behavior that it seems”, WARC, March 24, 2020.

10 Chris Stokel-Walker, “Coronavirus Timeline: How The World Will Change Over The Next 18 Months”, Esquire, March 25, 2020.

11 See, for example, Sara Benwell, “BOG OFF! Shameless supermarket ‘cashes in on toilet paper coronavirus panic by hiking price 60%’”, The Sun, March 15, 2020

12 See CMA Tesco/Booker 2017 and Booker/Makro 2012.

13 UK Competition Authority, CMA approach to business cooperation in response to COVID-19, CMA118, March 25, 2020.

14 See Sainsbury/Asda 2019.

15 https://www.comscore.com/Insights/Blog/Coronavirus-pandemic-and-online-behavioural-shifts.

16 https://www.which.co.uk/news/2020/03/online-marketplaces-coronavirus-update-ebay-and-amazon/.

17 “Price Gouging has no place in our stores” Amazon News, March 24, 2020.

18 Hannah Walsh, “eBay and Amazon failing to prevent sellers profiteering during coronavirus crisis” Which?, March 25, 2020

19 Sean Poulter, “’Rogue retailers are cashing in on coronavirus fear’: Government could regulate prices of key goods to stop profiteering as regulator slams ‘rip-offs’” The Mail Online, March 5, 2020.

20 See also Frame-Wilson v. Amazon.com Inc.

21 Frame-Wilson v. Amazon.com Inc., W.D. Wash., No. 20-cv-424, complaint filed 3/19/20.

22 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/protecting-consumers-during-the-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic-update-on-the-work-of-the-cmas-taskforce/protecting-consumers-during-the-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic-update-on-the-work-of-the-cmas-taskforce.

23 For a period of 6 months in the 1973 oil crisis Case 77/77 Benzine Petroleum v. Commission.

24 See, for example, Case 77/77 Benzine Petroleum v. Commission.

25 CMA v. Flynn and Pfizer March 10, 2020.

26 At para 59 the Court of Appeal reviews the reasoning in paragraphs [248] – [253] of the EU decision in United Brands before reviewing the relevant caselaw – of the EU and the English authorities. These paragraphs address three components. The legal test for abuse, they then describe what this means in economic terms, and then they describe the methods and evidence that might be relevant to proving the abuse. The CoA concludes at para 97 which is summarised above.

27 An element deserving consideration is the possibility that, together with an increase in volumes, sellers may face also an increase in the volatility of these volumes. This volatility increase might give rise to a real option to be accounted for in the calculation of a “reasonable” remuneration on invested capital.

28 One would have to consider if and how the competitive field changes. Suppose the number of oligopolistic competitors decreases after the restrictions reduce consumers’ ability to shop around. It would be hard to argue that the ensuing increase in equilibrium prices would be abusive.

29 CoA, CMA v. Flynn & Ors, para 112.

30 Ibid. para 97.

31 See also the DOJ on how it is dealing with profiteering/hoarding of medical products: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/department-justice-and-department-health-and-human-services-partner-distribute-more-half.

32 BRITISH WARTIME CONTROL OF PRICESJAMEs S. EARLEY* AND WILLIAM S. B. LACY The Ministry of Supply was created pursuant to the Ministry of Supply Act of July 13, 1939. This Act, together with the Emergency Powers (Defense) Act 1939 and, most importantly, Regulation 55 issued pursuant thereto empowered the competent authority to set maximum prices, and a set of other controls.

33 As of January 2019, 34 states have laws against price-gouging. Price-gouging is often defined in terms of the three criteria listed below:

- Period of emergency: The majority of laws apply only to price shifts during a declared state of emergency or disaster.

- Necessary items: Most laws apply exclusively to items essential to survival, such as food, water, and housing.

- Price ceilings: Laws limit the maximum price that can be charged for given goods.

Some states that do not have a specific statue addressing price gouging, can nevertheless apply the law as an “unfair” or “deceptive practice” under a consumer protection act.

34 California Penal Code 396 – which can be triggered by cities and local counties- revised recently to counter rental rate rises caused by housing being burned, massive increases in rents caused by lack of available accommodation.