By Philip Marsden & Rupprecht Podszun1

The EU Commission is stepping up efforts to come up with new regulations for digital gatekeepers. Executive Vice President Margrethe Vestager proposes a “New Competition Tool” and some form of “ex ante regulation” for platforms.

We offer proposals for sensible ex ante rules and enforcement frameworks to restore balance to digital competition. Other studies have established that there is a need for a better legal framework for digital gatekeepers. We now move on to the “how”:

- How do we design new tools and regulation to correct market failures in relation to digital platforms before the abuses of market power happen?

- How do we re-set the balance so that genuine innovation and choice prevail, and all businesses have an equal opportunity to compete in the marketplace?

- How do we ensure that the best product wins, not just the platform that offers it?

Three principles should guide the search for new rules: freedom of competition, fairness of intermediation, and the sovereignty of economic actors to take their decisions autonomously. These principles are described intentionally as having a constitutional character and importance and thus should be the foundation of any new EU regulation in this area.

These principles inform our new Sensible Rules – or “Do’s and Don’ts” – which set out obligations and prohibitions relating to Platform Openness, Neutrality, Interoperability and On-platform Competition; Non-discrimination; Fair terms; Controllability of algorithmic decisions and Access to justice; and Access to information; Respect for privacy; Choice on the use of data, and Choice for customers; Simplicity, not Forcing.2

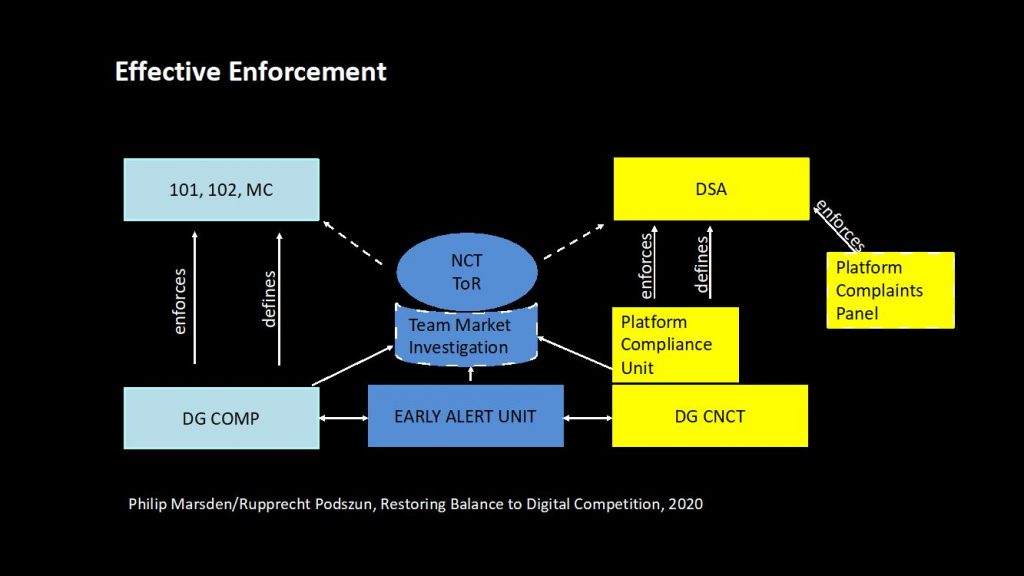

The most important part, however, is the stage of enforcement. What institutional design do we need? How do we enforce new rules? This is the core issue of the whole debate, not least since classic ex post antitrust enforcement takes too long and has achieved too little so far. Our proposal is the following:

|

Effective enforcement must keep pace with market dynamics, and requires sensible and flexible rules. As the underlying study underpinning our thinking was written during the German Presidency of the EU, and in the context of discussions leading up to enactment of a Digital Markets Act, and creation of a New Competition Tool, our proposals are necessarily European in institutional focus. However, we welcome developments to create Digital Markets Units and ex ante regulation in other jurisdictions, and thus hope our proposals will offer inspiration for how all competition authorities and digital regulators can work best together to restore digital competition.

The reasons for new regulatory efforts vis-à-vis digital giants are obvious: Some market platforms and aggregators have tipped the balance of market power among themselves, and others – particularly small businesses and consumers. Some of the fundamentals of commerce have changed as business has moved to a digital environment. There are many benefits from this as well – in terms of increased opportunities from scale, scope and reaching new markets. Consumers have benefitted from greater choice, speed of delivery and a feeling of engagement, tailored solutions and even advertising. However, several government and academic studies and investigations have found violations of antitrust, consumer protection, and privacy law, including combinations of them all. Germany has been a leader in this regard, offering inspiring studies, targeted legislative amendments and leading investigations. Nevertheless, the problems are bigger than any one nation can remedy. And in many cases even European findings of infringements have not always been able to be remedied. They have attracted enormous fines, but only after long and tortuous litigation, with many appeals. And only rarely has the actual ill-conduct been remedied, and if then, all too late or in a piece-meal and incomplete manner.

The actual causes of these ills are asymmetric market power, not only between giant platforms and aggregators on the one hand, and small businesses and consumers on the other, but also as between the tech giants and government itself. The balance needs to be re-set, or a levelling of the regulatory playing field if you will. This calls for new thinking to address new problems, and new competition tools and asymmetric and ex ante regulation to address the growing and troubling asymmetry of market power and its resulting inequities. The crucial task is to implement this new and necessary set of instruments without undoing or jeopardizing the many benefits of the new digital environment, to do so “in real time,” and to do so in a way which ensures that competition law, consumer protection, and privacy guarantees are upheld and balanced. To do nothing is not an option. First, because the inequities of the imbalances of power will only worsen. Second, because this in turn would lead to political calls for vast regulatory change which could stultify what are undoubted exciting and vibrant markets. What is needed – we argue – are sensible rules, backed up with effective enforcement. Relying on ex post law enforcement is insufficient: we urgently need new rules, and new institutional capabilities to guarantee effective enforcement.

To make one point clear: A new regulatory approach is not the ultimate and only answer to the many transformations of digitization. European politicians need to do much more – incentivize innovation, create a digital infrastructure, take care of those left behind, or educate children in using digital tools. All this is beyond our study – the regulatory framework for gatekeepers is merely one part of restoring balance.

Rules for Effective Enforcement

Effective enforcement of ex ante rules relies on three key factors:

-

- Compliance with these rules should be automatic and swift.

- Enforcement requires new institutional capabilities, and a strong interplay between these functions and the responsible officers (e.g. both within and between DG COMP and DG CNCT, with national institutions, and market actors).

- Rules need to be flexible enough so that they can be updated without legislative proceedings that are too complicated.

As such, we welcome enactment of a new Market Investigations Regime, as contemplated in the consultation for the New Competition Tool, implemented by DG COMP. We note insights from the similar tool in the UK show how it has already operated in some markets to impose interoperability and data portability remedies on platforms, accelerating innovation, technological development, and competition. Market investigations can be readily implemented at the EU level, including related to binding timelines, open processes, and independence of decision-making. The read-across between market investigations remedies, themselves a form of ex ante regulation, and a regulatory regime is clear. We see a need and opportunity for a strong interplay between market investigations by DG COMP, and evolving regulation, for example, by DG CNCT.

Securing the Interplay in Brussels

We propose a much stronger interplay between, in particular, DG COMP and DG CNCT in enforcing the new rules effectively.

Making the DGs act much more in concert means to look at their specific qualities: DG COMP is the only body in the European Commission having a vast experience in direct contacts with undertakings. Officials there are used to leading investigations, interpreting data, defining remedies and sanctions, sometimes battling with parties. Direct enforcement should rest with this body. DG CNCT and DG GROW are strong policy-making departments that have a broader view on economic and social needs in the EU. They can assure that the legal framework for platforms is not out of touch with two essential aims of this Commission: Building the digital single market and unleashing the power of digital innovation. They also have a view on the social costs that may come with certain platform behavior as well as with regulation. It is important to connect their policy-making power with the competition principles that are primarily pursued by DG COMP.

Market Investigations and Ex Ante Rules

Clearly, we support the introduction of a tool on the European level that is close to the Market Investigation tool in the United Kingdom and elsewhere. The charm of these investigations is that the team looking at markets can investigate without prior infringement or suspicion of infringement. The focus is much broader: Do markets function? Such investigations start as a fact-gathering endeavor with all market participants joined at the table, and it moves to remedies that are discussed and may address individual undertakings, but also regulatory boundaries. We find it important that governments and the EU may also be targeted by such investigations and that the teams come up with suggestions of how to amend the market framework. In the UK, this has led to the much-applauded Open Banking initiative, for instance.

Equally clearly, while we view market investigations as a valuable addition to the Commission’s competition toolkit (with enforcement of Art. 101, 102 TFEU and merger control remaining in full force), they are unlikely to provide a complete solution to competition concerns in digital platforms. As such, the Commission’s proposed new ex ante regulatory instrument for large digital platforms is necessary. Ex ante rules in the form of do’s and don’ts provide clear guidance for companies. We need to move beyond the P2B-regulation with its requirements of transparency since transparency does not help if you are dependent or in an unfavorable bargaining position.

As such, and to assist both of its competition and regulatory initiatives, we recommend that the Commission establish two new units. First, at DG CNCT, a Platform Compliance Unit for new and specific regulatory obligations. And second, within DG COMP, an Early Alert Unit relating to tipping markets. Additionally, for the New Competition Tool, we propose to have independent Market Investigation Teams.

| Market Investigation Teams

For Market Investigations with the New Competition Tool, we suggest that each investigation gets its own terms of reference and is conducted by an independent panel that is composed of experts – including, of course, Commission staff. The decisions of this panel should be independent. |

| The Platform Compliance Unit

At DG CNCT, a new “Platform Compliance Unit” would be formed that is competent for the ex ante regulation of platforms, monitoring platforms and issuing compliance orders, as well as forward-looking guidance. To this end, the P2B-regulation would have to be amended and turned into a regulation that provides a framework for digital platforms in the European Union. In order to retain flexibility, the regulation should foresee two special features: Firstly, there should be a possibility to subject certain undertakings and sectors to a special rule (asymmetric regulation). Secondly, the Platform Compliance Unit would need some flexibility in defining new rules without going through the burdensome procedure of an amendment of an EU regulation. This speaks in favor of a more flexible legal provision that can be amended in an easier fashion. Such a rule could take the form of a delegated act, provided that the essential features of rules on remedying structural imbalances in markets are set forth in the basic regulation. New rules should be based on the outcome of a market investigation. The Platform Compliance Unit would also be in a position to exempt certain platforms from some or all of the obligations. This will be particularly helpful for new market entrants or platforms with less deep pockets so that concentration processes of the large companies (e.g. Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook) may have a counterweight in the market. Before declaring these obligations binding, the parties would of course be heard and the Early Alert Unit at DG COMP consulted. |

| The Early Alert Unit

Within DG COMP, an Early Alert Unit would investigate where a tipping of markets is suspected of developing. To this aim, the Early Alert Unit should regularly monitor markets where it is likely that a platform may change the market structure in the near future. Such an investigation would not be as elaborate as a sector inquiry or a market investigation, but simply amount to a monitoring and largely be fueled by publicly available information and voluntary information provided from market players. If the Early Alert Unit has indications that a competition for the market is going to take place and a “tipping” is likely in the near future, based on scenarios experienced so far, it could suggest that the set of substantive rules are made binding for the relevant platform and be complied with. This would require early communication and concurring decision-making with the Platform Compliance Unit at DG CNCT. This is not to hamstring a nascently successful platform, or impede it from growing swiftly to a position of genuine success, or what we call natural tipping. But that growth must not be through anti-competitive acts or features for example, through exclusionary acts, banning multi-homing, self-preferencing, or non-transparent practices or misuse of data, nor must the tipping itself jeopardize the effective functioning of markets, through, for example, exclusionary or exploitative behavior. |

An example of the interplay

We foresee the Early Alert Unit as having the ability to identify the causes of tipping markets, engage with platforms and others to identify the extent to which a further market investigation is warranted, and throughout be able to engage with the Platform Compliance Unit in DG CNCT, to ensure that reasonable rules have been complied with during the platform’s growth. The role of the Early Alert Unit could thus be described as that of an investigatory arm of DG CNCT’s Platform Compliance Unit. The Early Alert Unit’s function extends to recommending a market investigation. If it appears that behavior is occurring that involves a violation of our rules, and this is contributing to the platform’s growth and a potential unnatural tipping of the market, then the solution is not to await another two years of further market investigation. The first act instead is to communicate with the Platform Compliance Unit and get the rules obeyed, and the platform in compliance. This may avoid the rationale for a market investigation and its attendant delay for worthwhile remedies. The operating principle throughout should always be to remedy problems as expeditiously as possible, ideally through mandating compliance with our ex ante rules. To enable quick measures, an appeal against such a compliance order would not have suspensive effect unless otherwise ordered by the courts.

The Early Alert Unit would also be able to propose new substantive rules for the platform regulation to the Platform Compliance Unit at DG CNCT. The proposal would also be vetted by DG COMP’s Chief Economist Team and the Legal Service before being made to DG CNCT. DG CNCT would have an obligation to consider and reply substantively to the proposal within a set period of time.

The Early Alert Unit should closely cooperate with national competition agencies and could delegate some of its market monitoring powers to these authorities depending on usual principles of effectiveness. In this regard a more active engagement of the European Competition Network is viewed as useful, as well as proportionate.

Ex ante rules and compliance with them can be monitored by the Platform Compliance Unit, akin to a supervisory function, but there needs to be an actual enforcement mechanism to handle disputes, as well as build up precedent.

| The Platform Complaints Panel We suggest introducing a Platform Complaints Panel that works like an arbitration mechanism or an ombudsperson for platforms. It should draw on independent adjudicators, potentially with experience in the sectors affected, and offer a rapid remedy to violations that are observed by market participants. The system would thus give a quick remedy to those who wish to stop certain practices by the operator at fast pace. Instead of leaving this to the public judiciary or the Platform Compliance Unit that may be easily overburdened or to an arbitration mechanism set up by the platform operator, it would be best to have an independent panel to regulate the claims. Upon direction by the Platform Compliance Unit, certain platforms of a particular status would be subjected to submitting to such a panel. In this regard we recommend a standing panel of independent adjudicators, supported by staff from DG CNCT, and with powers to decide on complaints brought by private parties where an allegation of a breach of the rules is made. This Platform Complaints Panel would operate swiftly, relying on a paper-based adjudication mechanism with strict timelines, with the only operating principle being to identify whether a platform is in violation of the rules, identify any objective justifications, and order corrective measures if necessary to restore competition. Appeals may be on the merits, but would necessarily be swift, given the adjudicative approach intended.

The panel would be competent to deal with individual concerns and complaints relating to conflicts of users with the platform, but also users on the platform with each other. A typical example may be that a supplier of goods on a marketplace complains that the platform does not disclose transaction data as required in a possible ex ante rule. The Platform Complaints Panel would look at the case and order a quick remedy for the parties. |

Conclusion

In our view, it is necessary to define the principles first that should govern our vision of living in a digitized economy. We stick to the principles of free competition, fair intermediation, and sovereignty of users in decision-making. This leads to sensible rules – in the following Appendix – that have to be respected by platforms due to the unique characteristics of digital platforms (operating with network effects and large amounts of data). These rules, often coming from individual competition cases, should go into an ex ante-rulebook for platforms. Whether all platforms should be targeted in the same way is a different question. We think that some rules may extend to all digital platforms, some platforms may be exempted, remedies may be tougher for large gatekeepers.

Secondly, it is vital to model the New Competition Tool according to the experiences in the United Kingdom with the Market Investigation Tool. The advantage of such a regime is that it enables the body to look into the whole market without biases or pre-determination. It also makes sure to come up with tailored remedies that at a next stage could go into the rulebook as ex ante rules. Obviously, certain safeguards for this regime are vital. In particular, we advocate to make the panel conducting a market investigation largely independent from other institutions and to have external experts on board.

The third pillar of effective enforcement is a regime that is tailored to the deficits with competition cases in the platform economy. Since competition law enforcement proved to take too long, we advocate an interplay of DG CNCT overseeing the reasonable ex ante rules and DG COMP as the strong enforcement body of the Commission. We wish to secure their interplay combining their strengths. An Early Alert Unit is to be set up at DG COMP to step in where a platform is about to gain a “winner takes it all” position. A Platform Compliance Unit is to be set up at DG CNCT dealing with policy and the ex ante rules for platforms. Both bodies need a close cooperation mechanism. Finally, enforcement should foresee a Platform Complaints Panel that resolves the issues of compliance with the help of market participants in a swift manner. These three bodies strictly address only situations where there is a structural imbalance of powers.

The ideas sketched in this paper are just that – ideas. They do not represent a final conclusion, but are an invitation to discuss with public and private stakeholders how the institutional set-up could be further developed to be fit for the platform economy.

Appendix

Sensible rules

| Rules for free competition

Openness: Platforms must not impose undue restrictions on the ability of users of the platform (business or consumers) to use other providers that compete with the platform or to compete with the platform themselves. This rule is aimed at exclusivity arrangements. Such arrangements can take the form of direct contractual obligations or indirect obligations having the same effect or technical restrictions that make it impossible to switch to other providers without a substantial loss. A particular form of this affecting suppliers and customers are attempts to hinder portability of data. If customers cannot move their acquired information, contacts, etc. to another platform or service provider, competition will not be possible. Neutrality: Platforms must not mislead users or unduly influence competitive processes or outcomes by employing means to self-preference their own services or products (or where the platform derives a commercial benefit) over services or products of competitors. Such a differential treatment, for instance through rankings that are based on the profitability for the intermediary platform, may be misleading for customers, drain companies that depend on the platform and harm competition. The rationale for this rule can be found in the Google Search (Shopping) case, the practice is also currently under investigation in the complaint by Spotify against Apple. Interoperability: Platforms must make it possible for undertakings to build products that are interoperable. Interoperability guarantees competition, it must not be unreasonably restricted. Similarly, APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) must be open so that third party technology can be integrated and become a competitive tool. Interoperability has become key in the digital economy – where this does not work, the provider of the foreclosed technology will be able to set up technological lock-ins for suppliers and customers. Interoperability is an established feature of competition law ever since the Microsoft case. On-platform competition: Platforms that have created marketplaces must ensure that there is free on-platform competition. If, for instance, competitors agree on prices or discriminate against others, it is the platform operator who needs to take the first steps. This may be a matter for competition by design (taking technological precautions, for instance against the visibility of certain information for other suppliers) or a part of the liability of the organizer of a forum for what happens in that forum. Whoever makes the rules in a marketplace needs to respect the ordre public – including antitrust rules. |

| Rules for fairness of intermediation

Non-discrimination: Platforms must not discriminate against individual suppliers seeking access to the platform, and may only base any exclusion on substantive, transparent, and objective grounds. In a scenario where one platform won the race for organizing the market, competition takes place at the periphery. Suppliers of goods and services need to get access to the platform. In such a gatekeeper situation, discrimination would amount to foreclosure of the market for specific suppliers. It would no longer be the customer who acts as the referee in the market, but the platform operator. Competition on the merits would be reduced. Such kinds of discrimination are viewed critically in competition law. Fair terms: Platforms must trade on fair and reasonable contractual terms, without exploitative pricing or acts The basic assumption of contract law is that the contractual partners meet on a level playing field and thus are able to secure a win-win-situation. Where one partner has such a structural advantage that the bargaining position is completely out of balance, the law needs to step in and find remedies. Controllability of algorithmic decisions, AI and reviews: Platforms must be transparent and fair about the working of their algorithms – and this needs to be controllable. Platforms may have considerable influence over the businesses of suppliers using the platform to match with customers. If such platforms change their terms & conditions, their rankings or other parameters, they may spark a domino effect for companies using the platform. The most stunning examples can be found where ranking algorithms are changed and thus companies tumble in their positions, making it virtually impossible for some to reach out to customers. Access to justice: Platforms must submit to an independent arbitration mechanism. Market actors enjoy the right to seek redress if there are conflicts with business partners. Since the public judiciary is often too slow and too costly for many disputes, platforms should bind themselves to an arbitration system – for disputes between the platform and users (be it commercial or consumers), but also for disputes among users of the platform. |

| Rules for sovereignty of decision-making

Access to information: Platforms must give access to customer and transaction data to the suppliers involved in that transaction. Platforms squeeze in between suppliers and consumers. For companies offering goods or services this means that they may lose the interface with their customers. Information and transactions are often operated by the platform in a way that does not necessarily guarantee a flow of relevant information to the supplier. This means that important business signals (such as price data) may be lost. Therefore, platforms must give access to customer and transaction data to the suppliers involved in that transaction. This idea forms part of the Amazon investigations and is also to be found in Section 19a of the German Draft Bill. Respect privacy: Platforms must offer a real choice on the use of data (which data, which application, which sources, combination of data). As the German Federal Court of Justice has argued, this is not just a matter of privacy rules, but – as in the Facebook case – a matter for competition and constitutional law. As a starting point, platforms need to keep the use of data in line with the principle of data minimization (only asking for the data essential for the service) unless customers had a real choice to decide otherwise. Give a choice: Platforms must allow customers to take decisions. These decisions should relate to the most important economic decisions: What services to use, how to spend money. The more such decisions are taken by the operator, the more users and suppliers are driven out of their decision-making capacity (example: introduction of a payment service that has to be used mandatorily, or providing a browser with the operating system without leaving the user a real choice). As in the Microsoft browser case, offering a drop-down-menu may serve as a countermeasure. Keep it simple: Platforms must give users the service they ask for, but not impose mandatory extensions of service. Again, this follows from the line of reasoning set out be the German Federal Court of Justice in the Facebook case. Providing all sorts of services, usually aiming at making the customer more dependent or incentivize her to stay for longer in the digital ecosystem, resembles the problem of illegal tying: Competition on the merits is again replaced by the use of leverage effects. Remedies include a fair design of default modes so that informed customer choice is really facilitated. |

Click here for a PDF version of the article

1 Philip Marsden is Professor of Law and Economics at the College of Europe, Bruges, and Deputy Chair, Bank of England, Enforcement Decision Making Committee, and a former Inquiry Chair at the UK Competition and Markets Authority. Rupprecht Podszun is a full professor for civil law and competition law at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Germany, and an Affiliated Research Fellow with the Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition, Munich. The contribution is based on a study that we did for Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, a policy think tank based in Berlin. We were completely free to pursue our own views.

2 An appendix to this article includes our proposals for sensible ex ante rules.