By Fay Zhou, Arthur Peng, Vivian Cao & Xi Liao1

The Chinese State Administration for Market Regulation (“SAMR”) published on January 2, 2020 draft amendments to the Anti-Monopoly Law for consultation (the “Consultation Draft”). The Consultation Draft retains the key concepts, analytical framework and major substantive rules under the current Anti-Monopoly Law (“current AML”), while seeking to clarify ambiguous provisions, codify settled views and introduce proposals to solve issues arising from enforcement practice over the past decade. Further legislative processes will still subsequently take place to consider these amendments leading to a prospective revised AML (the “prospective AML”).

We discuss in this article some of the key changes proposed, their implications and what remains to be clarified. These changes include introducing new conduct rules to capture “facilitators” of monopoly agreements, inclusion of technological factors for assessing dominance, changes to the concept of control, a “stop-the-clock” mechanism, and significantly increased penalties. Questions remain, such as the burden of proof regarding express prohibitions (like hard-core cartels), the legal basis for safe harbor rules, criteria for collective dominance, how the “stop-the-clock” mechanism may be used, and the burden of proof for monopoly agreements (particularly regarding penalties). These questions are considered in turn below.

Monopoly Agreements

a. New rules to capture “facilitators” of monopoly agreements

The Consultation Draft seeks to explicitly prohibit undertakings from coordinating or facilitating monopoly agreements. Such conduct is not directly captured by the current AML. The current AML only prohibits monopoly agreements (1) between competing undertakings, and (2) between an undertaking and its trading counterparties (i.e. horizontal and vertical monopoly agreements, respectively). It does not provide a legal basis for sanctioning third parties who co-ordinate or facilitate such agreements as long as the third party is not itself a party to such agreements. However, such third parties’ conduct would be considered a violation under the proposed Consultation Draft and subject to the same penalties as those who are parties to the underlying monopoly agreement.

While this is a welcome development in that it can fill the gap resulting from a potential narrow reading of the scope of “horizontal agreement” (e.g. a non-competing facilitator of cartel agreements may not technically be captured by the current prohibition against horizontal agreements), further clarity (e.g. through future implementing regulations) on the extent of involvement required to be found to be a “facilitator” would be welcome. For example, to establish an infringement, does it require the alleged “facilitator” to have had knowledge of the monopoly agreements being coordinated, or to have had an intention to facilitate? On its face, the scope of the proposed provision appears rather broad, and could potentially be interpreted to capture parties only remotely connected to the underlying agreement, e.g. the provider of the meeting venue.

b. Requisite anticompetitive effect of monopoly agreements

The Consultation Draft contains a definition of “monopoly agreement” which applies to both horizontal and vertical agreements. This addresses the previous confusion caused by the current definition of “monopoly agreements.” Under the current AML, the definition of “monopoly agreements” is based on the types of horizontal monopoly agreements set out in the same provision. This has led to confusion as to whether a finding of a vertical monopoly agreement (e.g. resale price maintenance) requires the establishment of anticompetitive effects. The Consultation Draft provides conceptual clarity and makes it clear that anticompetitive effects are required to establish both horizontal and vertical monopoly agreements.

The Consultation Draft, however, does not take a further step to set out the burden of proof: e.g. whether anticompetitive effects can be presumed, and who bears the burden of proving the existence of anticompetitive effects or rebutting any presumed anticompetitive effects. Such further clarity would be very helpful, considering the different approaches in public enforcement and private actions towards conduct expressly prohibited under the current AML (e.g. hard-core cartels and resale price maintenance). In public antitrust enforcement, the SAMR has clearly confirmed that its approach is similar to “by object” violations under EU law or “per se illegal” agreements under U.S. law, i.e. presuming their anti-competitive nature, as can be seen from its Interim Provision on the Prohibition of Monopoly Agreements and its enforcement actions. However, the Chinese courts are still inclined to consider, in private antitrust litigation, that even for conduct that is explicitly prohibited by Articles 13 and 14 of the current AML, it is necessary for the plaintiff to prove the effect of restricting or eliminating competition to establish claims based on alleged monopoly agreements. It would be helpful if the prospective AML would clarify this point, so as to bridge the gap, and enhance consistency between public enforcement and private litigation.

c. Prohibition of monopoly agreements

The Consultation Draft does not modify the existing language prohibiting monopoly agreements, i.e. certain conduct is expressly prohibited, such as hard-core cartels, while there is a catch-all provision for “other types of agreements.” This leaves the question of safe harbors unanswered for “other types of agreements.”

For such “other types of agreements,” which are generally subject to an analysis of effects on competition, the community has long called for safe harbors for certain types of horizontal/vertical agreements, i.e. a rebuttable presumption of legality if certain thresholds are satisfied, which are usually primarily based on market shares. This is established practice in other established jurisdictions, and brings significant benefits to enforcement agencies and companies. A previous draft version of the SAMR implementing regulations for monopoly agreements contained safe harbor rules based on market shares. However, these rules were not adopted in the final version of the implementing regulation, despite the fact that the proposal was widely welcomed by the community – it was understood that the concern was that the current AML does not specifically empower the SAMR to presume the legality of agreements based on objective criteria such as market shares.

Therefore, expectations remain for the prospective AML to provide more flexibility regarding the SAMR’s enforcement power for “other types of agreements,” although the specific mechanics, such as the thresholds for qualifying for the safe harbor, could be considered separately in the implementing regulations when deemed appropriate.

Abuse of Dominance

a. Finding dominance: recognition of factors specific to the “new economy,” and no changes regarding collective dominance

In addition to the factors for finding dominance already listed in the current AML, the Consultation Draft includes new elements when assessing dominance in technology-related markets, such as network effects, economies of scale, lock-in effects and the ability to control and process relevant data. This suggests that antitrust enforcement in the technology sector has become and will remain a focus of the Chinese authority in the future.

The Consultation Draft remains unchanged with regards to the criteria for finding collective dominance, including the hotly debated presumption of collective dominance based on market shares. It may be time to pause and consider whether to maintain the same criteria.

In general, the theory of “collective dominance” has not been widely recognized globally. It is not generally adopted in the U.S., and is only applied in limited situations in the EU. It involves a complex assessment, given that a finding of collective dominance would usually require a consideration of multiple factors, including market structure (e.g. market shares, entry barriers, transparency) on the basis of which competitors may detect (common) strategies employed by others, whether (tacit) co-ordination is sustainable over a period of time, and whether the foreseeable reactions of other competitors or consumers could jeopardize or undermine any common strategy.

As such, the current presumption of collective dominance based on market share could be an over-simplification, and may lead to unintended results. For example, a company with a 10-20 percent market share (hence not falling into the carve-out for companies with market shares of not more than 10 percent) could be deemed to hold a collective dominant position along with two larger competitors, if all three have 75 percent market shares overall. It may be difficult for such a smaller company to even be aware that it is contributing to a collectively dominant position. If it does conduct a compliance assessment, it would need to first find out its major competitors’ market shares and trading terms with customers and so forth, which in itself may increase market transparency and raise red flags under competition law.

Therefore, it seems reasonable to consider a more holistic approach (as opposed to a market-share based presumption), or alternatively an enlarged safe harbor. presuming no collective dominance, to reduce the compliance risks/challenges for smaller undertakings in oligopolistic markets.

b. Abusive behavior: removal of “equivalent conditions” in the criteria for discriminatory abuses

In relation to abuses of dominance, the Consultation Draft removes the “equivalent conditions” requirement to find the existence of discriminatory treatment. This seems to shift the burden of proof from the SAMR (or plaintiffs) to the investigated or sued party. The SAMR or the plaintiff would no longer need to prove that trading parties are in equivalent situations when impugning differentiated treatment. Rather, the investigated/sued company may defend itself by proving that the trading parties are in different situations, and thus that different treatment was justified.

However, the implications of the proposal may be broader and result in ambiguity – it could be interpreted to mean that different treatment can be found to be abusive even if the trading parties are in dissimilar conditions. To avoid misunderstandings, it may be best to maintain the “equivalent conditions” wording in the prospective AML, or at least to clarify, either in the prospective AML, or in its implementing rules, that “dissimilar conditions” remains a valid defense or a justifiable reason that the investigated company may rely on when defending differentiated trading terms.

Merger Control

a. Jurisdictional changes to merger control: definition of “control” and authorization for the SAMR to adjust notification thresholds

A definition of “control” is introduced in the Consultation Draft. It clarifies that “control” includes direct/indirect control, sole/joint control and de jure/de facto control. “Decisive influence” is defined as a form of control right, and is no longer a concept that exists in parallel with “control,” as under the current AML. This is a welcome change, as it sheds additional light on how the SAMR approaches the notion of “control.” What remains to be provided is detailed guidance on specific deal structures, e.g. how a “shifting alliance” situation would be approached by the SAMR. Such detailed guidance will be of great importance, particularly considering that the penalties for failures to notify are proposed to significantly increase.

The Consultation Draft also introduces a more flexible mechanism with respect to the notification thresholds. Similar to the situation in the U.S., the SAMR will be granted the power to modify the notification thresholds as it sees necessary. The current turnover-based notification thresholds, which were set by the State Council in 2008 under the authorization provided for in the current AML, are widely perceived as starting to lose pace with China’s rapid economic growth and thus warrant reconsideration. Granting the SAMR the power to adjust the notification thresholds means more flexibility, which is a welcome change that may bring the notification thresholds more in line with rapid and dynamic economic development. It remains to be seen how adjustments will be implemented in the future.

b. Introduction of a “stop-the-clock” mechanism in merger filings

The Consultation Draft provides that time spent in the following situations is not counted towards the 180-day statutory merger review period, i.e. the clock is stopped: (a) upon an application by or consent from the notifying party; (b) where supplementary documents and materials are required from the notifying party by the SAMR; and (c) while negotiating remedies between the notifying party and the SAMR. It is understood that one important “motivation” behind introducing the “stop-the-clock” mechanism is the SAMR’s goal of reducing “pull and refile”2 situations in its review of complex merger cases.

That said, the Consultation Draft remains relatively high-level and provides the authority with considerable discretion, which could result in timetable uncertainties. For example, the parties’ application or consent could potentially be made or given in any case. Parties in practice normally tend to be co-operative during the review process, and it is quite rare for them to refuse to give such consent to the authority. It may also be difficult to define the period of remedy negotiations, especially the starting point, e.g. whether that is point at which the SAMR identifies its competition concerns, when the first defense regarding such competition concerns is submitted, or when the first remedy proposal is made. Further complications arise in cases where the parties contest certain competition concerns but propose remedies for others in parallel. Further, it may be sensible to consider that questionnaires from authorities are a usual part of merger filing proceedings, and that the review clock should be stopped only in circumstances where a response is not provided within a reasonable time period.

Therefore, it is expected that the prospective AML (or its implementing rules) will, in due course, provide more guidance, to reduce uncertainties while facilitating more effective interaction between the parties and the authorities during the review procedure.

Penalty Rules

a. Introduction/significant increases in penalties

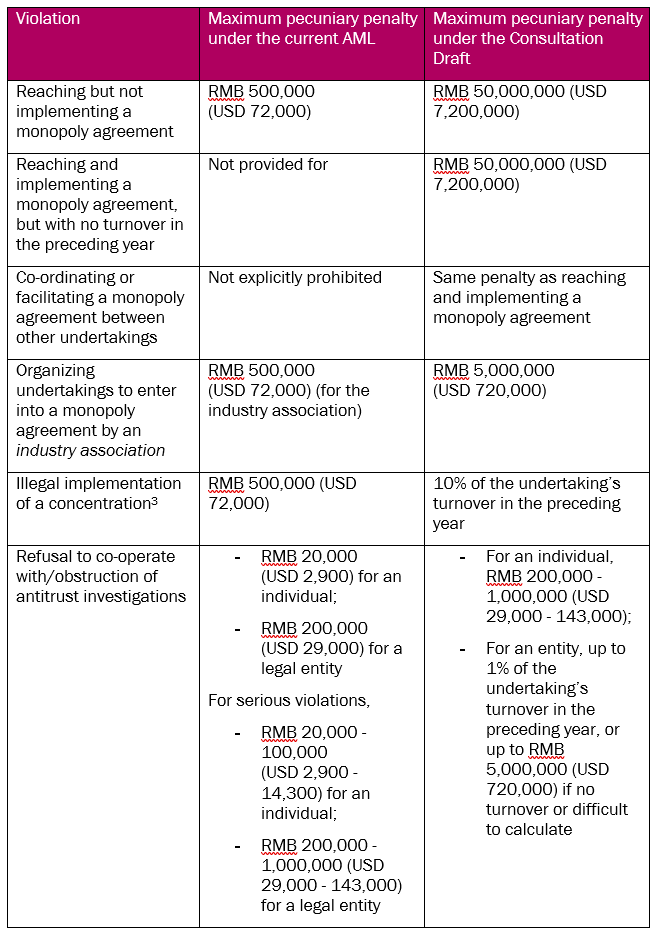

Arguably the most significant changes of the Consultation Draft concern the introduction of new pecuniary penalties and significant increases in the current ones. These include in particular fines for failures to notify and for reaching but not implementing a monopoly agreement. See below a brief summary/comparison. The more substantive issues are discussed in the following sections.

b. Additional factor affecting level of fines

b. Additional factor affecting level of fines

In determining the level of fines, in addition to the considerations provided for in the current AML (the nature, gravity and duration of the violation), the Consultation Draft introduces a new element, i.e. the rectification of the consequences of the illegal act.

c. Anticipated further clarity to guide enforcement and compliance

Despite the above new rules, some issues relating to fines need further clarification to provide better guidance for antitrust enforcement and compliance by undertakings.

The Consultation Draft retains the wording of the current AML regarding the base turnover for calculating fines, which is “turnover of the undertaking in the preceding year.” There appears to be a textual uncertainty, i.e. whether this refers to “total turnover” or “relevant turnover.”4 It remains to be clarified in future regulations or enforcement actions how SAMR will balance deterrent effects and proportionality.

In addition, aggravating/mitigating factors should also be specified to the extent possible, to facilitate compliance. For example, the U.S. Department of Justice in 2019 issued a new policy which credits companies for qualifying compliance programs. It is worth noting that the SAMR and local AMRs have recently published a number of (draft) guidelines on compliance program, which are also intended to motivate companies to implement effective compliance programs.

Further, it remains to be seen how continuous infringements that commenced prior to the enactment of the prospective AML will be dealt with in respect of illegal conduct and failures to notify. The prohibition of monopoly agreements entered into but not implemented and rules against failures to file could be interpreted to have retrospective effect, i.e. covering the pendency of the current AML and the prospective AML. This gives rise to the important practical question of which set of rules should be used to determine fines.

Other Notable Proposed Amendments

The Consultation Draft also seeks to introduce changes in other noteworthy respects, which are intended to bring the AML more up-to-date:

- The Consultation Draft explicitly provides that the settlement and suspension of investigations are not available to hardcore cartels, i.e. price-fixing, output restriction and market allocation, which is consistent with prevailing international practice.

- Where a breach of the AML also constitutes a crime, the Consultation Draft provides that the undertaking may be investigated for potential criminal liability. According to the current Criminal Law, AML violations that might also constitute a crime include bid rigging and obstruction of law enforcement, etc. The Consultation Draft has not created any new forms of criminal liability per se, but it cannot be excluded that the Criminal Law may be amended in future.

- The competition authority’s power to investigate alleged abuses of administrative power to restrict or eliminate competition is confirmed by the proposed amendments. The competition authority’s power to sanction such conduct is also enhanced: aside from making rectification recommendations to the superior authority of the administrative organ concerned, the competition authority can also directly order the administrative organ to rectify its practices.

- Consistent with current enforcement practices, the implementation of the fair competition review regime is explicitly defined to be the responsibility of the competition authority.

Conclusion

While the Consultation Draft included many anticipated or welcome changes, some questions remain unanswered, as we briefly set out in this article. The current round of consultations finished on January 31, 2020 and the Consultation Draft will be revised for further review and assessment by the State Council and the National People’s Congress. Once enacted, the prospective AML will obviously have profound impacts on transactions and the business operations of many market players within and outside China.

Click here for a PDF version of this article

1 Fay Zhou is a Partner and Arthur Peng is a Managing Associate at Linklaters. Vivian Cao is a Partner and Xi Liao is a Counsel at Zhao Sheng Law Firm. Shanghai Zhao Sheng Law Firm (“Zhao Sheng”) is a partnership constituted under the laws of the People’s Republic of China (“PRC”) and licensed to practise PRC law and provide PRC legal services. Zhao Sheng Linklaters (FTZ) Joint Operations Office is a joint operation between Linklaters LLP and Shanghai Zhao Sheng Law Firm. The Joint Operation operates in Shanghai and has been approved by the Shanghai Justice Bureau. This publication is intended merely to highlight issues and not to be comprehensive, nor to provide legal advice. Should you have any questions on issues discussed here or on other areas of law, please contact one of your regular contacts, or contact the editors.

2 “Pull and refile” situations are common in complicated cases, involving the withdrawal of a filing and the re-submission of the filing and re-starting of the timetable, so that the review period extends beyond the statutory 180-day period.

3 There are four types of illegal implementation of a merger: (1) failure to make a merger notification, (2) gun-jumping (i.e. implementing the merger prior to obtaining clearance), (3) breach of remedy commitments and (4) implementation of a merger in breach of a prohibition.

4 Traditionally, Chinese competition authorities construed “turnover of the undertaking in the preceding year” as meaning “relevant turnover,” which is the turnover affected by the illegal conduct. In recent enforcement practices, the total turnover of the investigated undertaking has been used as the basis for determining fines. The SAMR’s current interpretation is that the non-existence of a qualifier before “turnover” in the current AML means that the scope of “turnover” should not be qualified, i.e. the basis for fine calculation should be the undertaking’s total turnover. This interpretation is also intended to enhance deterrence.