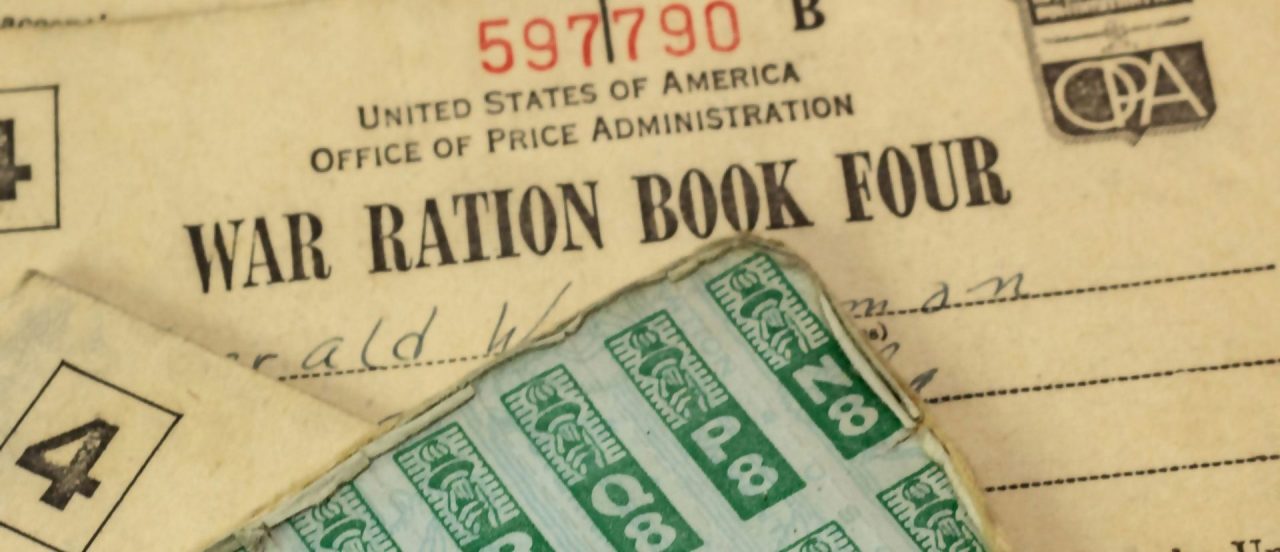

Shortages resulting from natural disasters invariably lead to allegations of price gouging. By themselves, price gouging laws exacerbate rather than alleviate shortages by preventing the price mechanism from discouraging hoarding and encouraging supply expansion. To retain customer loyalty, some businesses may limit their price increases and instead either impose their own rationing or accept stock-outs. Those private decisions do not justify legal sanctions against companies that do not exercise similar restraint. Given enough implementation time, an alternative to relying on the market mechanism to allocate scarce resources in a crisis-induced shortage is a rationing scheme such as the one United States used in World War II. During the COVID-19 crisis, such a policy may well have been both feasible and desirable for items such as personal protective equipment.

By Michael Salinger1

I. INTRODUCTION – CONTRASTING VIEWS OF ECONOMISTS AND THE PUBLIC

The conventional definition of economics is the study of the allocation of scarce resources among alternative uses; and both economic research and teaching focus heavily on the role of a decentralized price mechanism in accomplishing this task. In his 1979 Presidential Address to the American Economic Association, Robert Solow observed, “Ever since Adam Smith, economists have been distinguished from lesser mortals by their understanding of and – I think one has to say – their admiration for the efficienc

...THIS ARTICLE IS NOT AVAILABLE FOR IP ADDRESS 216.73.216.60

Please verify email or join us

to access premium content!