By Cheng Liu, Yun Bi & Jeff Liu (King & Wood Mallesons, Beijing)1

I. INTRODUCTION

The abuse of dominant market position is one of the significant infringements under China’s Anti-Monopoly Law (“AML”). According to public records, since the AML came into effect in 2008 (and as of June 30, 2020), the Chinese antitrust authorities have concluded 48 investigations against abusive conduct (this does not include the cases that were tried in courts). Thus, the administrative authorities have been able to accumulate more experiences and increased sophistication in investigating complicated issues in abuse of dominance cases.

In this article, we have reviewed and identified the key targeted industries and abusive conduct that attracted the authorities’ attentions in the previous administrative proceedings. Looking at recent enforcement actions may give us insight into the type of industries and conduct which enforcement authorities are most concerned with.

II. MOST TARGETED INDUSTRIES

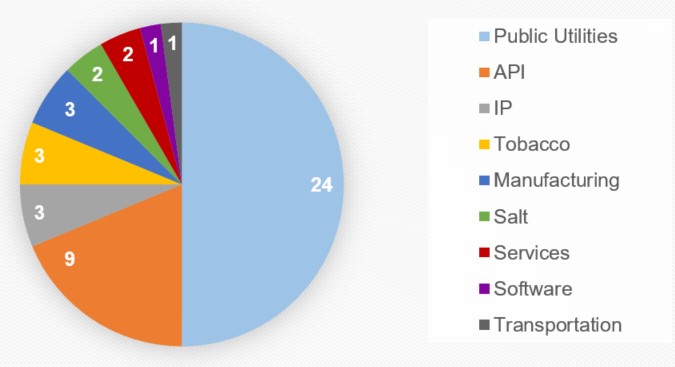

Sixteen industries, ranging from banking, public utilities to pharmaceutic industries, have been targets of abuse of dominance investigations. Among them, the most frequently targeted industries are (i) public utilities, tobacco, and salt; (ii) active pharmaceutical ingredient (“API”); and (iii) high-tech and IP.

Among them, the most frequently targeted industries are (i) public utilities, tobacco, and salt; (ii) active pharmaceutical ingredient (“API”); and (iii) high-tech and IP.

Unsurprisingly, public utility (water, gas, electricity, telecommunication, etc.), tobacco and salt companies were the top target given that they are essentially natural monopolies in China. Altogether, there have been 29 investigations (24 investigations against public utilities, 3 investigations against tobaccos and 2 investigations against salt companies) against them which were publicly announced and closed/suspended.

The second most frequent target of abuse of dominance investigation from Chinese authorities, in terms of the number of investigations, have been API suppliers. In China, there are specific requirements and high barriers for manufacturing APIs. Therefore, there are only limited number of suppliers of APIs, who usually hold high market shares and thus more likely to be caught by Chinese authorities.

Multinational companies in the high tech and IP sectors were the third most frequent target of abuse of dominance investigations, in terms of number of cases. While there have been only three investigations against “high-tech”/IP sectors so far, they were all against well regarded multinational companies, i.e. Qualcomm, Tetra Pak, and InterDigital, and considered as landmark cases in China’s AML enforcement. There have also been reported of on-going/potential investigations against other multinational high-tech companies such as Microsoft and Ericsson, although no official decisions have been announced.

The above statistics are also consistent with what Chinese authorities have publicly stated about their enforcement priorities. In the past three years, in the authorities’ statements about their enforcement priorities, sectors concerning peoples’ livelihood (including public utility, APIs, daily necessities, etc.) have always been mentioned.2

In recent years, it appears that SAMR has also started to pay closer attention to the conduct of the major internet giants. For example, SAMR and its local authorities have ever received the complaints against Tencent Music,3 and Meituan4 in 2019 for abuse of dominant market practice.

However, so far, the Chinese authority has not officially penalized any internet platform companies. One possible reason is the difficulty in establishing the existence of a dominant market position in the fast-changing internet sector. In Qihoo 360 v. Tencent,5 the Supreme Court set a relatively high bar for the plaintiff to establish that an Internet company holds a dominant market position, which may cause the administrative authority to also be cautious in determining that any Internet platform company holds a dominant market position in its administrative investigations. Also, in the context of the broader competition for consumers’ attention, competition is not limited in certain specific products or services, but broadly extends to competition between different types and areas of products and services6. For example, while online shopping malls (like T-mall) and online videos platforms (like Tencent) provide difference services to consumers, they all seek to attract and compete for the attention of consumers, which make them compete with each other to a certain extent. This makes it more difficult to clearly delineate and define a proper relevant market, and thus more challenging for the authority to establish that any specific company holding a dominant market position.

III. MOST TARGETED CONDUCT

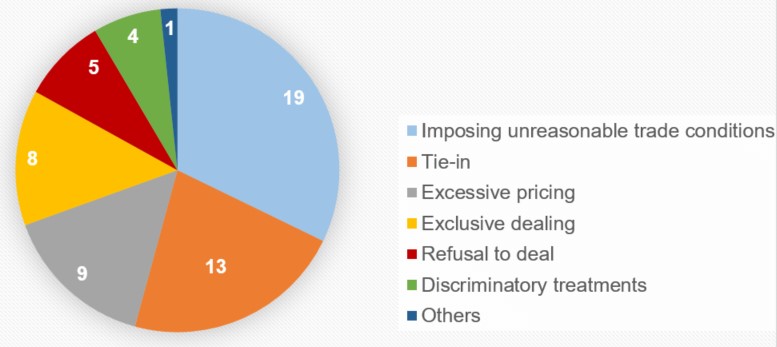

The AML has specified seven types of typical abusive conduct, namely: (i) selling at excessive price or purchasing at an unfairly low price; (ii) selling at below cost prices without justification; (iii) refusal to deal without justification; (iv) imposing exclusive dealing requirement without justification; (v) imposing unreasonable trade condition; (vi) tying without justification; and (vii) discriminatory treatment on the counterparties at the same conditions without justification..

Based on the statistics, among the 48 investigations, the most targeted conduct types are (i) imposing unreasonable trade condition; (ii) tying; (iii) excessive pricing; and (iv) exclusive dealing.

3.1 Imposing unreasonable trade conditions

There have been 19 investigations where the authorities found the abusive conduct of imposing unreasonable trade conditions had occurred. The concept of imposing unreasonable trade definitions is very broadly defined and thus conceivably all types of trade conditions that a company may ask its counterparty to accept could be covered by this. Based on past investigations, typical types of conduct which has been considered to be imposing unfair conditions include:

- Forcing the counterparties or consumers to pay deposits or pre-pay services fees

In Nanjing Lishui District Power Supply Branch of State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., LTD. (“Nanjing Electricity Supplier”), decided in August 2018,7 Nanjing Electricity Supplier was found to impose unreasonable trade conditions by requiring the users to pre-pay the electricity fees based on the 80% of electricity consumption in the last month. If the users do not agree to pre-pay, Nanjing Electricity Supplier will refuse to supply electricity to them.

2. Requiring the counterparties to deal with the designated vendors;

In Tianjin Tap Water Supply Group (“Tianjin Water Group”),8 decided by SAMR in July 2019, Tianjin Water Group was sanctioned due to requiring real estate developers to use intelligent frequency conversion control cabinets and remote monitoring substations manufactured by its subsidiary in the construction of real estate developers’ secondary water supply facilities. If developers choose another vendor, then the water supply facilities construction will not be approved by Tianjin Water Group.

3. Requiring the counterparties to exclusively deal with the company or sell back all final products to the company.

In Calcium Gluconate API Distributors,9 decided by SAMR in April 2020, the three API distributors were penalized for imposing unreasonable trade conditions, including on one hand forcing the APIs manufacturers to sell all products to them (via purchasing in a large volume, and requiring exclusive supply rights), and on the other hand forcing preparation manufacturers to sell all the final products back to them or act as their exclusive OEMs in accordance with their instructions. Otherwise, these three distributors will refuse to supply the API to the non-compliant preparation manufacturers.

We noticed that some of the “unreasonable trade conditions” found in these cases may also be considered as “exclusive dealing” which is another specific type of infringement listed in the AML. It may also be more difficult to distinguish other types of unreasonable trade conditions conduct such as “forcing pre-payment” from legitimate business arrangements. Therefore, when designing and negotiating the trade terms, companies with comparatively strong deal position or bargaining power need to be cautious with imposing restrictive requirements to the counterparties, and assessments of its market position and the effects of such conditions are recommended.

3.2 Tying

Since the first tying investigations in 2013, there have been 13 investigations against tying arrangements. The business models investigated in those cases are all similar (and not complicated), i.e. companies were found to tie the unpopular products to popular products, to enhance the sale of the unpopular products.

One observation is that, in most of the 13 cases, companies tried to defend their tying arrangements by “justifications,” such as previous transaction practices, or public health and safety concerns. For example, in Qinghai CNPC,10 the Qinghai CNPC Company required its users to install wall-hanging ovens that it manufactured, and argued that this tying arrangement was due to public safety reasons. In the Tetra Pak Case,11 Tetra Pak argued that tying the packaging materials into its equipment and technical services is for the purpose of ensuring public health and food safety. However, in neither of these cases, did the authorities accept such public health and safety concern arguments, because the authorities consider the tying arrangements were not necessarily relevant to the public health and safety, and there is no factual or legal basis to prove that the tying product has better performance than the third parties’ products in terms of compliance with the mandatory safety or quality requirement. Therefore, while these “justifications” are provided in the regulations, the authorities have not actually accepted this argument in any of the 13 tying cases and it appears that the bar to proving the existence of this “justification” may be quite high.

3.3 Excessive Pricing

There have been 9 investigations involving excessive pricing, 5 of which were focused on API suppliers and 2 of which are relevant to IP licensing arrangement (i.e. the investigations into Qualcomm and InterDigital). There has been a lasting debate on whether “excessive pricing” should be considered an abusive conduct or market participants should have the freedom to set their own prices. The statistics show though that Chinese authorities have not hesitated to take actions in cases of “excessive pricing.”

API suppliers (5 of 9) have been a focal point for excessive pricing investigations as such investigations are usually caused by a substantial increase in the APIs’ prices, which easily raise the excessive pricing concern. In addition to APIs, the authorities are also concerned about whether there are any excessive pricing issues in charging licensing fees to domestic licensees by the licensors (e.g. in the Qualcomm Case12 and InterDigital Case13).

When determining whether the price is excessive in an administrative investigation, the business operator’s historical price, the price of other business operators, the cost and whether the increase of price is comparable to the increase of cost are key factors to be considered, and the authority usually will assess these on a case-by-case basis. Based on the previous investigations, we noticed that the authorities are more inclined to use the business operator’s own historical prices and the cost of products (including the increase of the cost) as a benchmark to assessing whether the price is excessive. For example, in the Calcium Gluconate API Distributors Case issued by SAMR in April 2020, the API distributors were challenged for excessive pricing, because (i) compared to the cost, the selling price was 9.5 to 27.3 times higher than the price at which they purchased the products from API manufactures; (ii) compared to the historical cost, the selling prince in 2017 was 19 to 54.6 times of that in 2014; and (iii) there are internal price increasing between the manufacturers and the distributors for selling its product. Therefore, it is recommended that companies holding a strong market position be very careful about the price increasing issue, especially the reason for price increases, and whether there is a cost increasing in the similar arrange in parallel.

3.4 Exclusive Dealing

There have been 8 investigations involving exclusive dealing issues. Except for Tetra Pak and Eastman,14 all of the other investigations are relating to public utilities (such as water supplier, electricity supplier, gas supplier, etc.).

In Tetra Pak and Eastman, the Chinese authorities have shown that they have become more sophisticated in dealing with complicated business scenarios. For example, in Eastman, it was the first time that SAMR reviewed the “Most-Favorable-Nation” (“MFN”) clause, and assessed it in combination with other arrangements (such as the minimum supply requirement) to conclude it may bring the effect of exclusive dealing and foreclose competitors from effectively participating in competition. In Tetra Pak, the authority assessed the exclusive dealing based on the restriction of technology R&D arrangements with the third party, and concluded that such technology R&D restrictions will have the effect of exclusive dealing.

3.5 Other targeted conduct

In addition to the abovementioned types of conduct, there have been 5 investigations involving the refusal to deal issue and all of them are in relation to the APIs manufacturers/distributors, who refuse to supply APIs to the drug manufacturers. There have also been 4 investigations involving the discriminatory treatment, involving the companies providing internet access, salt, tobacco, and transportation services at the port.

In Tetra Pak, the authority also considered that Tetra Pak’s retroactive discount caused exclusionary effects, but eventually categorized it under the catch-all clause of “other abusive conduct,” rather than “exclusive dealing,” for reasons not specified in the final decision. However, this shows that business arrangements that may have exclusionary effects will likely catch the authorities’ attention, and SAMR is likely to look at conduct beyond the typical abusive types specified under Article 17 of the AML, and focus more on the effects of conduct.

IV. CONCLUSION

In general, the Chinese authorities have been relatively active in investigating abuse of dominant market position. While in terms of the number of investigations, most investigations focused on the public utility area and API suppliers, high-tech companies, IP licensing arrangements and internet companies have attracted close attention from the authorities in respect of the abuse of dominant market position issues. In particular, it is recommended that multinational companies should take a cautious approach with respect to IP licensing arrangements.

In practice, some abusive conduct (such as imposing unreasonable trade conditions) are very general and may cover various commercial arrangements, and thus authorities have applied a broad interpretation in assessing and determining abusive conduct. While the typical types of abusive conduct under Articles 17(1) to (6) of the AML continue to be the key enforcement targets, the authorities are more sophisticated and prepared to comprehensively review more complicated commercial arrangements, such as the discount policy (in Tetra Pak) and MFN clause (in Eastman). The authorities are more focused on the actual impact on the market competition of the conduct, rather than the form of the conduct. Certain business arrangement (such as MFN clauses) may still be caught for abuse of dominant market position, even if it is not an explicitly prohibited conduct under the AML. Therefore, companies are recommended to be cautious when assessing and negotiating the commercial terms with the counterparties, especially if those terms will add restrictions/onerous obligations on the other side.

Click here for a PDF version of this article

1 Cheng Liu (Partner), Yun Bi (Senior Associate) and Jeff Liu (Senior Foreign Legal Consultant) are at King & Wood Mallesons, Beijing office. The authors would like to acknowledge the research support of Mengzhen Wang, legal assistant.

2 See Promoting Competition Enforcement and Safeguarding Fair Competition – the Anti-Monopoly Enforcement Priorities in 2019 (http://www.cicn.com.cn/2019-01/09/cms114232article.shtml); Focus of Pricing Regulated and Anti-Monopoly Enforcement by the National Development and Reform Commission in 2018, http://fgw.wulanchabu.gov.cn/Article/HTML/1677.html; Focus of Pricing Regulated and Anti-Monopoly Enforcement by the National Development and Reform Commission in 2017, http://fgw.wulanchabu.gov.cn/Article/HTML/934.html.

3 See Tencent Music faces antitrust allegations in China after competitor complaint – sources, https://app.parr-global.com/intelligence/view/1679560.

4 See China’s Nanchong city antitrust regulator probing Meituan, https://app.parr-global.com/intelligence/view/1941670.

5 See Beijing Qihu Technology Co., Ltd. v. Tencent Technology (Shenzhen) Company Limited and Shenzhen Tencent Computer Systems Company Limited re Abusing Dominant Market Positions ((2013) Min San Zhong Zi No.4).

6 See David S. Evans, Attention Rivalry Among Online Platforms.

7 See Decision of Suspension of Investigation on Nanjing Lishui District Power Supply Branch of State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., LTD. (Su AIC Zhong Zi [2018] No. 1).

8 See Administrative Penalty Decision on Tianjin Tap Water Supply Group issued by Tianjin Administration for Market Regulation (Jin Shi Jian Ji Fa Zi [2019] No. J1).

9 See Administrative Penalty Decision on the Monopoly of Calcium Gluconate API (Guo Shi Jian Chu [2020] No.8).

10 See Administrative Penalty Decision on Qinghai Shengmin and Chuanzhong CNPC for Abuse of Dominant Market Position (Qing Shi Supervision Monopoly Zi [2020] No.1 and 2).

11 See Administrative Penalty Decision on Tetra Pak for Abuse of Dominant Market Position (AIC Competition Zi [2016] No.1).

12 See Administrative Penalty Decision on Qualcomm Incorporated (Fa Gai Ban Price Jian Penalty (2015) No 1).

13 See the National Development and Reform Commission Suspended the Investigation on US IDC for Pricing Monopoly http://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xwzx/xwfb/201405/t20140522_612465.html.

14 See Administrative Penalty Decision on Eastman for Abuse of Dominant Market Position (Hu AMR Chu Zi [2019] No. 000201710047).