By Joe Kennedy (ITIF)*

Introduction

The United States is in the middle of a renewed debate on antitrust policy. Although most antitrust experts favor keeping some form of the current policy, perhaps with slightly firmer enforcement around the edges, a growing number of policy advisors and elected officials favor radical changes that would target firms simply for the sin of bigness. They allege that rising concentration in most markets has given a growing number of firms significant market power that harms not just the economy, but broader society as well. Lax antitrust enforcement has supposedly led to diverse harms such as the stagnation in wages, fewer startups, increased political influence, and reduced innovation.

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation recently began a Monopoly Myths series examining some of the specific claims put forward by advocates of radically restructuring antitrust law, including claims regarding higher profits and markups.1 In most cases we find that the empirical evidence behind these claims is weaker than claimed. In other cases, the casual relationships are speculative. In still others, the claim is downright wrong.2 Although some of the broader issues, such as privacy and political power, raise important social concerns, these have several causes and antitrust policy is not an effective response. Broader social policies are needed.

Two of the most important claims are that profits and markups are rising in many industries.3 These trends purportedly have been enabled by widespread increases in market concentration and resultant declines in competition. The popular press has published a multitude of articles and op-eds repeating this argument. These rely on several academic papers that purport to show significant rises in both profits and markups since the 1980s.

On closer inspection, however, both claims appear weaker than asserted. Profits have indeed risen from the turn of the century until a few years ago. However, they are still below the levels of the 1960s, when antitrust enforcement was much stricter; increases in non-financial domestic profits have been minimal; and they have been falling for several years. Markups are more difficult to measure and interpret. However, given the limited increase in profits, it seems likely that much of any increase is due to the growth in intangible capital (which is not included in markup measures and which makes it appear that markups over costs have gone up), rather than to market power. In these conditions, it is possible for a firm to have high markups but zero profits.

Getting these issues right is important, for if there is a structural increase in profits and in firms’ ability to raise prices, this raises important issues for antitrust policy and casts doubt on the entire antitrust consensus of the last half century. On the other hand, if most of this is a tempest in a teacup, which it appears to be, it suggests that radical reform of antitrust practice is not needed.

Popular Claims Regarding Markups and Profits

Central to the thesis of America’s antitrust problem is the claim that markups and profits are increasing. Basic economic theory states that in a perfect market prices would not exceed marginal costs and company profits would not exceed their normal cost of capital. (Thankfully we don’t live in that world, because if we did there would be little to no innovation). If one firm gains market power, however, it will be able to raise prices above marginal cost and increase profits. This has two effects. First, the higher price transfers some welfare from consumers to the firm. Second, the higher prices push other consumers out of the market, making society worse off. The ultimate source of harm is the increase in prices. Without an increase we would have to wonder whether consumers are suffering any harm.4 And yet, general inflation has been well under the Federal Reserve’s target of two percent for several years, even as the economy expanded.

In 2016 The Economist wrote that among S&P 500 firms, domestic profits (excluding foreign earnings) were at near-record levels relative to GDP.5 Former Clinton Administration Labor Secretary, Robert Reich believes recent changes in the economy have “resulted in higher corporate profits, higher returns for shareholders, and higher pay for top corporate executives and Wall Street bankers — and lower pay and higher prices for most other Americans.”6 Liberal economist Joseph Stiglitz wrote “we live in an economy where a few firms can get for themselves massive amounts of profits and persist in their dominant position for years and years.”7 In 2016 Paul Krugman wrote that “profits are at near-record highs.”8

Similar claims have been made regarding markups. Bonnie Kavoussi of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth wrote “markups and corporate profits have been on the rise since the 1980s.”9 Stiglitz claims: “There has been an increase in the market power and concentration of a few firms in industry after industry, leading to an increase in prices relative to costs (in mark-ups). This lowers the standard of living every bit as much as it lowers workers’ wages.”10

Concentration Is Not at Extreme Levels

As part of its Monopoly Myths series ITIF looked at whether market concentration is actually increasing as much as antitrust critics complain.11 One has to be careful to define the correct market, which is often much smaller than the 6-digit definitions provided by the North American Industry Classification System (“NAICS”). ITIF’s report found that, when measured at the national level, concentration in about two-thirds of industries has increased from 2002 to 2012 (the latest federal data available). But in most of those industries it remains significantly below levels that would normally trigger antitrust scrutiny.12 For example, the combined market share of the top 4 firms in the packaging machinery manufacturing industry (NAICS 333993) increased by almost 30 percent during that time period. But the actual increase was from 24 percent of the market to 31 percent. If all of the top 4 firms were the same size, each would have only a 7.5 percent market share. Other studies have found that local concentration in many industries, which is often the most relevant market for consumers, has actually fallen.13 Finally, it is possible that greater competition is leading to greater concentration rather than the reverse, as explained below.14

Profits Have Increased Only Modestly

Determining whether claims about profits are true is not an easy exercise. Economist Susanto Basu warns “profits are notoriously hard to calculate.”15 The federal government only provides data on profits as a share of GDP and by industry and firm size. It does not provide firm-level data on either revenues or costs. Even when firm-specific data exists, calculating profits requires a number of important assumptions. The most difficult involves separating the normal return to capital from pure profits, especially since the former depends on the riskiness of the investment, which is itself difficult to measure, and changes by industry and over time.16 Moreover, there are multiple ways to measure profits.

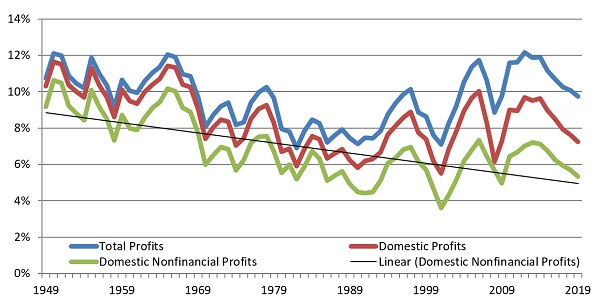

Nonetheless, when looking at actual profits over time, the story of rampant and growing monopoly does not hold up. Figure 1 shows pre-tax domestic nonfinancial profits as a percent of GDP after adjusting for inventory and capital consumption. This is the best measure for several reasons. Pre-tax income shows the total profits companies earn in the marketplace. Its trend is not directly influenced by changes in tax policy. Foreign profits are not relevant because any increase in market power within domestic markets would only affect domestic profits. If foreign profits are rising because of a lack of competition abroad, that is a problem for foreign antitrust officials. I also exclude financial firms due to their volatility, heavily regulated nature, and ability to extract rents.

In fact, the trendline for domestic, non-financial profits is down from the 1950s, and since the 1980s it has fluctuated around 6 percent, falling from the recent peak in 2013. In other words, profits are below the levels when antitrust policy was characterized by more aggressive cases, such as Brown Shoe and Vons Grocery. The fact that profits do not appear to be spiraling out of control brings into question whether market power has allowed firms to raise markups significantly.

Figure 1: Corporate profits as a percentage of GDP before tax and after inventory and capital consumption adjustments.17

But maybe large firms are using market power to take profits away from their smaller rivals. Tax data casts doubt on this theory. If companies were using market power to increase profits, we would expect larger firms to have higher profit margins. But data from the Internal Revenue Service shows that between 1994 to 2013 (the latest data available) net income as a share of total receipts grew 10 percent faster for firms with less than $5 million in revenue than it did for firms with over $500 million in receipts.18

But maybe large firms are using market power to take profits away from their smaller rivals. Tax data casts doubt on this theory. If companies were using market power to increase profits, we would expect larger firms to have higher profit margins. But data from the Internal Revenue Service shows that between 1994 to 2013 (the latest data available) net income as a share of total receipts grew 10 percent faster for firms with less than $5 million in revenue than it did for firms with over $500 million in receipts.18

Mark Up Studies are Flawed

Markups – the price charged over the marginal cost of production – present an even greater problem. Economist Chad Syverson wrote: “Markups are difficult to measure directly. They require information not just on prices but on hard-to-observe marginal costs.”19 There can be great uncertainty about what costs are marginal as opposed to fixed. Marginal price also varies by quantity and individual firm, and depends on the correct measurement of intangible investment. Basu notes that: “different assumptions and methods of implementation lead to quite different conclusions regarding the levels and trends of markups… Existing methods cannot determine whether markups have been stable or whether they have risen modestly over the past several decades.”20 Moreover, if over time more firms and industries increase their fixed costs as a share of total production costs, then markups would be expected to increase even in highly competitive markets. Finally, economist Steven Berry faulted recent studies on markups for employing an outdated analytical approach in which market structure determines outcomes, rather than newer models from industrial organization theory.21

Nevertheless, a number of prominent academic papers claim to find significant increases in both profits and markups over the last few decades. Economists Jan De Loecker, Jan Eeckhout & Gabriel Unger looked at company-level data on all publicly traded firms to measure both markups and profitability in the United States from 1955 to the present.22 They argue that beginning in 1980, the average profit rate (sales minus all costs as a percent of sales) increased from 1 percent to 8 percent.23 The paper also asserts that aggregate markups rose from 21 percent of marginal cost in 1980 to an astounding 61 percent in 2016.24

Leaving aside the fact that the average rate of profit was closer to 11 percent in 2016 (making one wonder where the 61-percent markups went), this widely cited study has also been widely criticized. Economist Tyler Cowen points out that, if profits are defined as the difference between market prices and the marginal cost of production (essentially markup), businesses with high fixed costs and significant economies of scale can have large “profits” and still lose money.25 Rohan Shah noted that the authors used accounting data to estimate their models, which is different than economic data. Even if economic profits are zero because of stiff competition, a firm may still show a profit in its accounts.26 Basu points out that the model used to achieve these results produces implausible estimates for other economic variables. For example, it implies that adding more capital to a process actually decreases output.27 Economist Chad Syverson examines De Loecker’s figures and finds that, even if profits were zero in 1980, the finding that pure profit rates increased from 1 percent to 8 percent, implies that corporations were able to convert 25 percent of all sales revenue into profits in 2016, leaving only 75 percent to cover all costs, including labor.28 This is much higher than most estimates. For example, in 2016 corporate profits as a share of net value added was only 17.7 percent.

In an earlier version of their paper, DeLoecker & Eeckhout provide data on a few companies, but these examples make little sense.29 GE’s markups supposedly increased by 44 percent between 1980 and 2014, even as its profit rate went down by 8.2 percentage points.30 Meanwhile, Apple and Wal-Mart, which are often accused of having significant market power, saw their markups decline slightly over the same period. This gets to the key problem with the markup studies: the growth of intangible capital.

Gauti Eggertsson and his colleagues used national and firm-level data to estimate changes to the share of corporate income going to profits since 1985. Initially, the pure profit share in excess of the normal cost of capital was only 3 percent of total income, with 63 percent of income going to labor and another 26 percent to capital (taxes took 8 percent). By 2015 the pure profit share had risen to 17 percent, while the labor and capital shares fell to 57 and 17 percent respectively (taxes rose to 9 percent).31 Eggertsson also found an increase in markups over the last 40 years, although much smaller than those found by De Loecker & Eeckhout. In their baseline case, markups increased from roughly 1.1 to 1.2 between 1987 and 2015. Despite this modest increase, they attribute to it an increase in concentration and profits and a fall in the share of income going to labor.32

Simcha Barkai estimated that between 1984 and 2014 according to the trend line, the share of total value added going to pure profit increased from -5.6 to 7.9 percent, a rise of 13.5 percentage points or over $1.2 trillion in 2014.33 But obviously pure profits cannot be negative for very long since it implies that the owners of capital are not even covering all of their costs. Some rise in the rate was therefore inevitable.

Besides mismeasurement, higher profits and markups might be due to an increase in competition rather than its decline. A number of studies support this thesis. Economists David Autor et al. used data from the U.S. Economic Census going back to 1982.34 They concluded that globalization and new technologies have increased competition within a number of industries. This in turn has pushed sales toward the most productive firms, which have lower costs and therefore higher markups. These benefits did not extend to the majority of firms in an industry because they did not have the lower cost structure from innovation and productivity. Median markups were flat or even falling. They also noted that these “superstar” firms tended to become more specialized within their industry, rather than trying to expand into other markets. The same trend occurred in Europe, which has more aggressive antitrust enforcement.

A recent study by the International Monetary Fund (“IMF”) provides further support. Looking at a large number of industries in different countries, it also found a consistent record of rising markups in developed countries, about 8 percent since 2000.35 For most country/industry pairs, higher markups were associated with more innovation. The 10 percent of firms with the highest markups were 30 percent more productive and relied 30 percent more on hard-to-measure intangible assets.36 Undervaluing these assets would produce inflated markups. All these correlations are consistent with causes other than market power, especially with the theory that international competition has increased, as some firms become more productive, partly by increasing their investment in intangible assets. These costs are often omitted from markups. Again, the fact that similar increases are occurring within other countries indicates that this is due to changes in global economic markets rather than changes in national antitrust enforcement. Within the United States, markups were driven mainly by a shift of market share within industries, reflecting in part “a growth-enhancing reallocation of resources away from low-markup, low-productivity firms toward high-markup, high-productivity counterparts.”37 The study found little evidence that pro-competition policies had weakened. This is especially true because the study weighted firms’ markups by firm revenue when calculating aggregate markups. If higher competition caused consumers to move away from firms with low-markups and toward innovative firms with higher markups because the latter provided more valuable products, then the industry markup will rise even if no company changes its individual markup.

Conclusion

The new “anti-monopoly movement” is based on a fundamental skepticism and even antagonism towards large firms. To achieve their goal of having fewer large firms and more mid-sized and small ones, the neo-Brandeisians must make a case that there is a problem. Without a serious problem, what’s the logic for overthrowing 50 years of antitrust doctrine? The key problems they assert are concentration, profits, and markups. In fact, a closer analysis suggests that none of these have increased in any significant way.

Although claims of greater concentration and higher profits and markups are common, the evidence is not compelling. Concentration has been rising in some industries, but in few to problematic levels. Moreover, it may be due to greater competition, not less. Profits as a share of value added have not been rising in the last five years or so and are below historic levels. The story of rising markups is even more problematic with most of that coming from an increase in intangible capital and business structure. Taken together, this evidence is certainly not enough to justify overthrowing the existing consensus on maximizing overall economic welfare (often referred to as the Consumer Welfare Standard) and bringing back a regime akin to the 1950s and 60s’ focus on conduct/structure/performance.

Click here for a PDF version of the article

* Joe Kennedy is a senior fellow at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. He focuses on economic policy.

1 Joe Kennedy, “Monopoly Myths: Is Concentration Leading to Higher Profits?” (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, May 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/05/18/monopoly-myths-concentration-leading-higher-profits; Joe Kennedy, “Monopoly Myths: Is Concentration Leading to Higher Markups?” (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, June 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/06/01/monopoly-myths-concentration-leading-higher-markups.

2 Robert D. Atkinson & Caleb Foote, “Monopoly Myths: Is Concentration Leading to Fewer Start-Ups?” (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, August 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/08/03/monopoly-myths-concentration-leading-fewer-start-ups.

3 The markup of a product is usually measured by dividing a product’s price by its marginal cost, including the necessary return to capital. In perfect competition prices equal marginal cost and the markup is one.

4 This focus on consumers is behind the Consumer Welfare Standard, which bases antitrust enforcement on whether there is an identifiable harm to consumers. In reality, antitrust policies also recognize that there can be damage to competition in other markets, including those for labor and innovation.

5 “Too Much of a Good Thing,” The Economist, March 26, 2016, https://www.economist.com/briefing/2016/03/26/too-much-of-a-good-thing.

6 Robert Reich, “Why We Must End Upward Pre-Distributions to the Rich,” RobertReich.com, September 2015, http://robertreich.org/post/129996780230.

7 Joseph E. Stiglitz, “America Has a Monopoly Problem—and It’s Huge,” The Nation, October 23, 2017, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/america-has-a-monopoly-problem-and-its-huge/.

8 Paul Krugman, “Monopoly Capitalism is Killing US Economy,” The Irish Times, April 19, 2016, https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/paul-krugman-monopoly-capitalism-is-killing-us-economy-1.2615956.

9 Bonnie Kavoussi, “How Market Power Has Increased U.S. Inequality,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, May 3, 2019, https://equitablegrowth.org/how-market-power-has-increased-u-s-inequality/.

10 Joseph E. Stiglitz, “America Has a Monopoly Problem—and It’s Huge.”

11 Joe Kennedy, “Monopoly Myths: Are Markets Becoming More Concentrated?” (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, June 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/06/29/monopoly-myths-are-markets-becoming-more-concentrated.

12 Gregory J. Werden & Luke M. Froeb, “Don’t Panic: A Guide to Claims of Increasing Concentration,” Antitrust Magazine, vol. 34(2), (Spring 2020), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3156912.

13 Esteban Rossi-Hansberg, Pierre-Daniel Sarte & Nicholas Trachter, “Diverging Trends in National and Local Concentration,” (Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Working Paper Series 18-15R, February 27, 2019), https://doi.org/10.21144/wp18-15; Kevin Rinz, “Labor Market Concentration, Earnings Inequality, and Earnings Mobility,” Center for Administrative Records Research and Applications, U.S. Census Bureau, Working Paper 2018-10, September 2018, https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/2018/adrm/carra-wp-2018-10.html.

14 David Autor et al., “Concentrating on the Fall of the Labor Share,” American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, Vol. 107(5), May 2017, 180, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20171102.

15 Susanto Basu, “Are Price-Cost Markups Rising in the United States? A Discussion of the Evidence,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 33(3), Summer 2019, 9, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.33.3.3.

16 Ibid.

17 Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Table 6.16, Corporate Profits by Industry, https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=19&step=3&isuri=1&nipa_table_list= 53&categories=survey.

18 Internal Revenue Service, SOI Tax Stats, Statistics of Business, (Table 5. Selected Balance Sheet, Income Statement and Tax Items, by Sector, by Size of Business Receipts), https://www.irs.gov/uac/soi-tax-stats-table-5-returns-of-active-corporations.

19 Chad Syverson, “Macroeconomics and Market Power: Context, Implications, and Open Questions,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 33(3), Summer 2019, 31-32, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.33.3.23.

20 Susanto Basu, “Are Price-Cost Markups Rising in the United States? A Discussion of the Evidence.”

21 Steven Berry, Martin Gaynor, and Fiona Scott Morton, “Do Increasing Markups Matter? Lessons from Empirical Industrial Organization,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 33(3), Summer 2019, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.3.44.

22 Jan De Loecker, Jan Eeckhout & Gabriel Unger, “The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 135(2) (May 2020), https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz041.

23 Ibid. 561.

24 Ibid.

25 Tyler Cowen, “The Rise of Market Power?” Marginal Revolution Blog, August 23, 2017, https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2017/08/rise-market-power.html.

26 Rohan Shah, “Margins and Monopoly,” Adam Smith Institute blog, August 21, 2017, https://www.adamsmith.org/blog/margins-and-monopoly.

27 Susanto Basu, “Are Price-Cost Markups Rising in the United States? A Discussion of the Evidence,” 16.

28 Chad Syverson, “Macroeconomics and Market Power: Context, Implications, and Open Questions,” 34.

29 Jan De Loecker, & Jan Eeckhout , “The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications,” (National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 23687, August 2017), 38, https://www.nber.org/papers/w23687.

30 Gurufocus. https://www.gurufocus.com/financials/ge.

31 Gauti B. Eggertsson, Jacob A. Robbins & Ella Getz Wold, “Kaldor and Piketty’s Facts: The Rise of Monopoly Power in the United States,” (NBER Working Paper No. 24287, February 2018), https://www.nber.org/papers/w24287.

32 Ibid. 26.

33 Simcha Barkai, “Declining Labor and Capital Shares,” Journal of Finance, forthcoming, (November 19, 2019), 13, https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3489965.

34 David Autor, et al., “The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 135(2) May 2020, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa004.

35 International Monetary Fund, “The Rise of Corporate Market Power and its Macroeconomic Effects,” Chapter 2 in IMF, World Economic Outlook, April 2019: Growth Slowdown, Precarious Recovery, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/IMF081/25771-9781484397480/25771-9781484397480/ch02.xml?language=en&redirect=true.

36 Ibid. 61.

37 Ibid. 68, italics removed.