By John D. Harkrider (Axinn, Veltrop & Harkrider LLP)*

Over the last six decades,1 millions of hungry Americans have pulled off the side of the highway, walked past a glowing yellow sign, slipped into a red leatherette booth — frequently after midnight — and stuck their forks into a Grand Slam breakfast. Indeed, Denny’s serves more than 12 million Grand Slam breakfasts a year, including more than 2 million after a Super Bowl promotion that promised free breakfasts between 6am and 2pm the Tuesday after the game.2 The next year they did it again with similar success. Likely fearing bankruptcy, they decided to stop the promotion.3

Denny’s has an interesting history. The company was founded in 1953 in Lakewood California as Danny’s Donuts. It quickly changed its name to Denny’s in order to avoid confusion with the Los Angeles restaurant Coffee Dan’s.4 Denny’s signature Grand Slam breakfast, which consists of eggs, sausage, bacon, and pancakes, was introduced in 1977 by its Atlanta restaurants in honor of Hammerin’ Hank Aaron, who had broken Babe Ruth’s home run record at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium.5

Denny’s is profitable, with revenue of more than $500 million, operating income of $165 million, and a healthy EBITA of $97 million.6 But it is hardly a monopolist. In fact, Denny’s has a market share of under 5 percent of franchise Table/Full Service Restaurant sales, competing with the likes of Applebee’s, Chili’s, Olive Garden, Cracker Barrel, Cheesecake Factory, and Waffle House.7

So why break up Denny’s? It is not because they bundle eggs, sausage, bacon, and pancakes together, it is not because they force franchisees to purchase goods from them as a condition of their franchise agreements, it is because they do these things and have a Return on Capital Employed (”ROCE”) of 55 percent,8 well above alleged Google’s 40 percent return that both the UK’s CMA, Fiona Scott Morton, and David Dinielli (Scott Morton & Dinielli) have argued demonstrates the existence of market power.9

If the CMA and Scott Morton & Dinielli are correct that a ROCE of over 40 percent demonstrates the exploitation of market power and justifies the breaking up of Google, so too it must justify the breakup of the feared monopolist Denny’s.

Using Profitability as Evidence of Market Power under American Law

In both its Interim and Final Report on Digital Advertising, the CMA argues that the fact that a firm has a ROCE above its cost of capital for a significant amount of time is evidence of market power.

In that context, the CMA argues that, “[w]e have found through our profitability analysis that the return on capital employed. . .[is] at least 40% for Google search.”10 Given that Google’s cost of capital was about 9 percent, the CMA concluded that “[t]his evidence is consistent with the exploitation of market power.”11 Scott Morton & Dinielli cite this conclusion as evidence that Google earns a “supra-competitive price for the services provided by the Google-controlled players in the ad tech stack,”12 ignoring, of course, that the CMA said nothing about Google’s ROCE in ad-tech or display advertising.

Most antitrust lawyers are unfamiliar with the term ROCE (return on capital employed). It has never been used by a court in any reported decision as sufficient evidence of market power.

But plaintiffs have tried to introduce profitability as a metric of market power in American courts, only to be repeatedly turned down. As the Seventh Circuit stated in Blue Shield United of Wis. v. Marshfield Clinic, “not only do measured rates of return reflect accounting conventions more than they do real profits (or losses). . .but there is not even a good economic theory that associates monopoly power with a high rate of return.”13 Another court noted: “The court is unaware of any reported federal antitrust case in which a defendant’s purported high rate of return, by itself, established market power.”14 And yet another court held that “citing accounting profits without more is unsatisfactory proof of monopoly profits, and in turn of monopoly power.”15

This is in accord with commentators like Areeda & Turner who note that “real economic returns on capital are difficult to measure and the proper methods of measuring economic profits are much disputed.”16

Indeed, Frank Fisher & John McGowan wrote a seminal article in 1983 On the Misuse of Accounting Rates of Return to Infer Monopoly Profits in the American Economic Review.17 As the authors explain, “accounting rates of return, even if properly and consistently measured, provide almost no information about economic rates of return,” which the authors define as “that discount rate that equates the present value of its expected net revenue stream to its initial outlay.”18 This is because “only by accident will accounting rates of return be in one-to-one correspondence with economic rates of return,” and “a ranking of firms by accounting rates of return can easily invert a ranking by economic rates of return.”19

Another useful peer-reviewed article is Profitability Tests in Competition Law and Ex Ante Regulation by Phillipa Marks & Brian Williamson.20 The authors conclude that ROCE is an improper metric for competition analysis, “for both conceptual and practical” reasons.

Further, Grout (2001) examined the history of cases reviewed by the UK Monopolies and Mergers Commission (“MMC”) (a predecessor to the UK Competition and Markets Authority) under the UK Fair Trading Act. This analysis found that, “[a]verage rate of return on capital employed has been 44%, with an average of 45% for cases where there was an adverse finding and 41% for those where there was no adverse finding. Looking at cases where the primary concern was potential monopoly pricing the figures are 61%, 67% and 48% respectively. For cases where the primary concern was abuse of vertical integration the figures are 52%, 54% and 51%.”21

Significantly, Grout found that “across all cases there is no statistical relationship between profitability and the Commission’s finding.”22 This casts real doubt on ROCE’s usefulness as a metric for determining whether a firm has market power. But even if ROCE were a reliable proxy of market power — which it isn’t — Google’s alleged 40 percent ROCE, as alleged by the CMA, is below the level historically found by UK Competition regulators in monopolization cases.

Regulating Google as a Utility

While ROCE has been questioned as a proxy for market power in antitrust analysis, it is a commonly used statistic in regulated industries, most specifically in utilities regulation. For example, under Texas regulation, when establishing a utility’s rate, the Public Utility Commission of Texas is required to set a rate that would allow “the utility a reasonable opportunity to earn a reasonable return on the utility’s invested capital used.”23 See also 49 U.S.C.A. § 10704 (the Surface Transportation Board should set a price that allows for “a reasonable and economic profit or return (or both) on capital employed in the business”).

Imposing a cap on appropriate profitability creates perverse incentives for firms. Consider a firm that has a 39 percent ROCE who is considering two possible investments: one has an uncertain return that if it succeeds would bring tremendous benefits to consumers, the second has a certain return that consumers regard with some level of indifference. Imagine that if the first succeeds, it brings ROCE over 41 percent, thus exposing the firm to ex post regulation as a monopolist. But if it doesn’t succeed, then it brings ROCE to well under 40 percent. Imagine that if the second succeeds, it does not impact ROCE at all. Under a regulatory regime that penalizes achieving a ROCE above 40 percent, the second is preferable because it has less execution risk, and does not create the risk of the firm being declared a monopolist. But this result sacrifices the possibility of tremendous benefits to consumers and interferes with a company’s normal business calculus of whether to engage in welfare enhancing endeavors. And if there is no disproportionate return for a successful investment that balances the cost of an unsuccessful one, then there is no incentive to make big bets on future innovation.

As Dennis Carlton noted, “Capping prices (and hence returns on investments) will, among other drawbacks, generally deter risky but economically desirable investments. This is hardly a prescription for innovation and economic growth. . .The more the law limits a firm’s anticipated profit from bringing a product successfully to market, the lower the incentive to do so in the first place.”24

This points to the real problem with using profitability as a rationale for antitrust enforcement, namely, that its true aim is to turn Google into a regulated utility. That suggestion may sound farcical to the millions of people who detest the slow, plodding, and expensive public utilities that serve them gas, electricity, cable, and landline phones, and love the fast, innovative, free, and constantly improving services of Google. But sad to say, it is the very objective of many of Google’s adversaries, who are themselves utilities. In a House Judiciary hearing involving Google, Congressman Steve King stated: “And one of the discussions that I’m hearing is ‘what about converting the large behemoth organizations that we’re talking about here [e.g. Google] into public utilities.”25

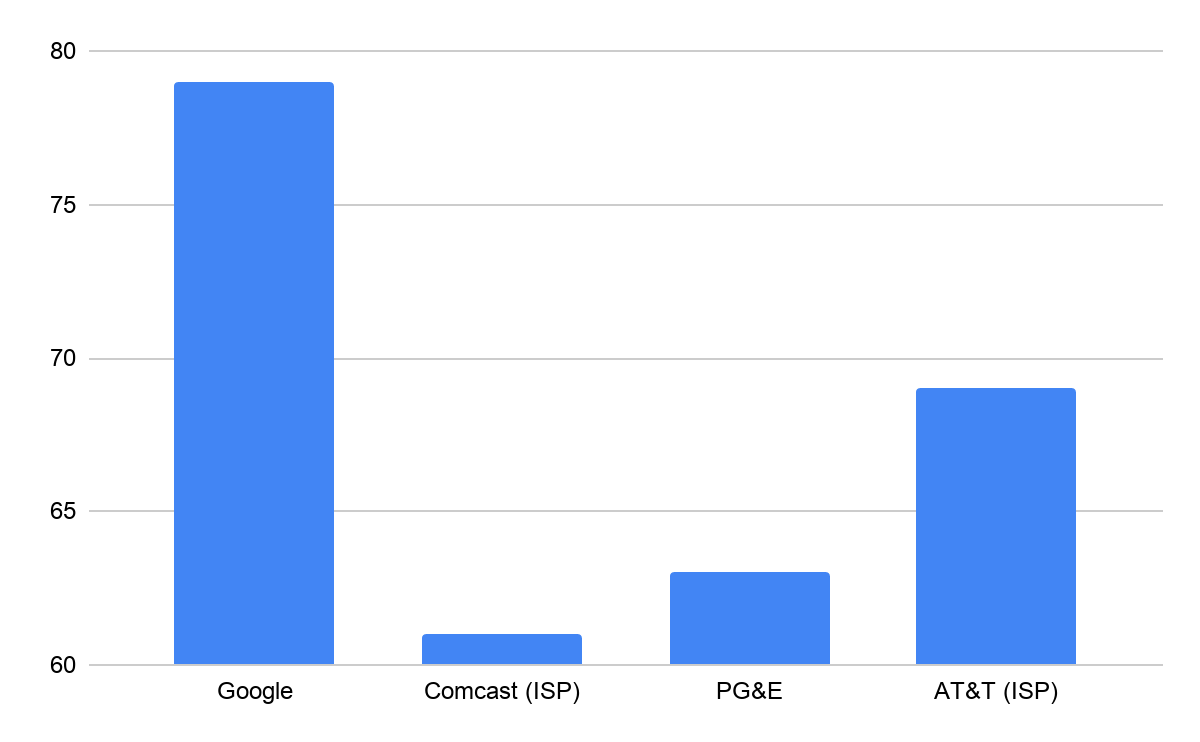

Do we really think it’s a good idea to turn Google into a public utility? Anybody who has waited days for the cable, telephone, or power company to respond to a service complaint knows firsthand that utilities are routinely slow to respond to consumer demand. For example, Comcast has regularly showed up last in the “customer service hall of shame.”26 More than 1 in 4 surveyed customers rate Comcast service as “poor.”27 One survey ranked Comcast as America’s most hated company.28 The fiber-optic television business of AT&T is also one of the lowest ranked companies in customer service, with reports of “inadequate call centers” and “providing customers with a window of time for home visits” that “often forces them to take time off work” due to the long windows.29

Do we really believe that the best way to level the playing field is to have it take just as long for Google to answer a search query as it takes for Verizon to send a technician to fix your phone line? Consider that according to the American Customer Satisfaction Index, Google is one of the most loved companies in the world. They are innovative and responsive to consumer demand. They invest billions of dollars to improve search and make ads increasingly relevant.

2019 American Customer Satisfaction Index30

As a public utility, Google would have had little incentive to innovate beyond the two or three seconds it took to return a search years ago. But instead, as a private company with the ability and incentive to make free-market business decisions, it invested billions of dollars to return searches in milliseconds.

As a public utility, Google would have had little incentive to innovate beyond the two or three seconds it took to return a search years ago. But instead, as a private company with the ability and incentive to make free-market business decisions, it invested billions of dollars to return searches in milliseconds.

The reason utilities are disliked is because they have less incentive than non-utilities to improve service or transform their business models, indeed, their upside is limited. They try to squelch disruptive business models rather than develop them.

But of course that is what critics of Google such as Comcast and AT&T actually want. Because it is easier for them to bring Google’s level of investment, innovation, and service down to their level than for them to rise to Google’s.

This is the teaching of the economics literature on regulatory capture and public choice. This literature also explains that, in general, the threat to competition posed by lobbying attempts to enact public restraints to raise rivals’ costs and harm competition are more pernicious than their private sector counterparts (i.e. private ordering) or reliance on existing and more flexible laws (like antitrust). This is because this form of rent-seeking does not have offsetting procompetitive virtues, and regulations that distort (or even destroy) competition are more insulated from market forces that would otherwise protect consumers.31

A Request for Analytical Rigor

If having a ROCE over a cost of capital of 9 percent is evidence of market power, then Google has a lot of company. Indeed, according to YCharts, more than 3,500 equities have a ROCE over 9 percent. These companies include Domino’s Pizza with a ROCE of 87 percent and Yum Brands with a ROCE of 57 percent.

One might quickly observe that Denny’s, Domino’s, and Yum Brands have something in common other than the quality of their food. They are all franchises and as a result do not put up significant capital for their business. Thus, it makes sense that these companies would have low costs of capital and high returns. But that does not make them monopolists.

But if ROCE isn’t a one size fits all metric of market power, then why do we think that it indicates that Google has market power? And if it doesn’t, why use it at all?

Indeed, one of the fundamental tenets of the scientific method is that tests be disprovable. If the hypothesis that ROCE is an indicia of market power, then one could look through all 3,500 equities with a ROCE over their cost of capital, and determine whether it is, in fact, a statistically significant relationship between ROCE and market power. If there is, great. If not, stop using it.

Funny Math

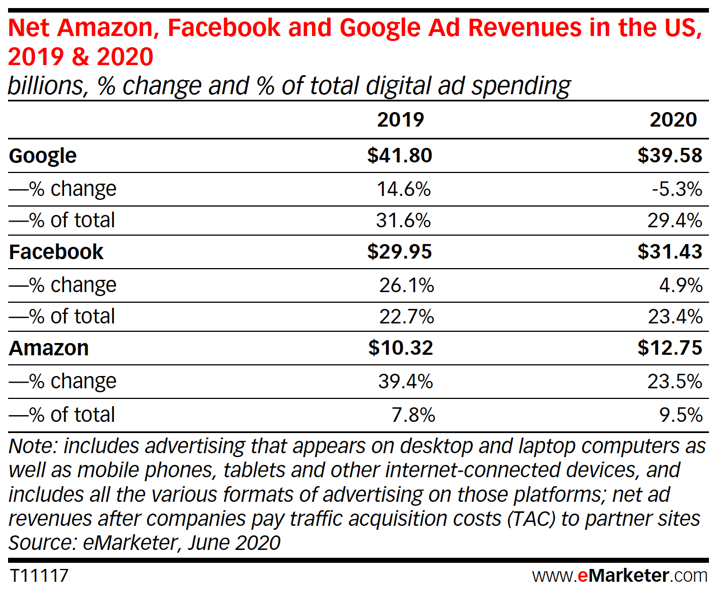

Taking a step back, it is striking that the case against Google completely lacks the rigor of a typical antitrust case. How is Google expected to dominate the digital advertising market where it faces strong and growing rivals in Facebook and Amazon?

Indeed, according to the CMA, “Facebook (including Instagram) is by far the largest supplier of display advertising, accounting for more than half of display advertising expenditure.”33 How can Google be a monopolist if there is another firm that has a larger market share? There is no offense for shared monopoly, at least not in the United States.

The idea that YouTube has market power is also based upon funny math. Scott Morton & Dinielli claim that YouTube’s market share in display is “up to 10%,” and that Facebook and Instagram have much higher shares of digital video than YouTube.34 But then they argue that YouTube does not compete with Facebook,35 which means that an advertiser such as Ford would not advertise on Facebook or Instagram instead of YouTube. Maybe that’s true. Maybe.

Scott Morton & Dinielli’s argument is that ads on user generated videos on YouTube are more similar to ads on feature movies and network television shows on Hulu than they are to ads on user generated videos on Facebook, Snapchat, or Instagram. If this statement were true, it would need to be supported by actual empirical evidence, estimated cross-elasticity of demand, not just a bald assertion of fact.

Why are We Ignoring these Statistics?

If we are to use obscure statistics such as ROCE as evidence of market power, should we not also consider the following statistics as well?

What about the fact that Google takes a lower share of publisher revenue than its rivals? Contrary to the exaggerated claims of some alleging Google’s fees account for 70 percent of ad spend,36 Google in reality charges a combined 31 percent,37 which is lower than CMA’s industry wide estimates of 35 percent.38 According to the CMA, Google’s product specific fees are “comparable” or “similar” to its competitors’ fees.39 Further, the CMA Final Report found that the evidence that they reviewed “does not indicate that Google is currently extracting significant hidden fees.”40 If higher prices are consistent with the existence of market power, as Scott Morton & Dinielli argue, then lower (non predatory) prices are consistent with its absence.

Or consider Scott Morton & Dinielli’s allegation that Google has an “insurmountable data advantage.”41 But how is this consistent with the observation that Google’s share of online advertising spend is shrinking, while Facebook’s and Amazon’s are growing? If Google has such a large data advantage, an advantage that nobody in the world will ever be able to match, then shouldn’t it follow that all advertisers would flock to Google and spurn data-poor Facebook and Amazon? And yet, all have substantially higher growth rates than Google.42

Or take the fact that Scott Morton & Dinielli misleadingly claim that “Google pays no ‘traffic acquisition costs’ because it needn’t pay any publisher for access to the ‘eyeballs’ that will see or interact with the ads it helps place.”43 YouTube has disclosed that it pays over 50 percent of its revenue to creators.44 With revenue of over $15 billion, this would imply an estimated $8 billion paid to creators.45 In contrast, much of Instagram and Facebook’s inventory generates no payments to content creators; for example, Instagram recently offered partners, but only 200, the ability to monetize via IGTV.46 Seems odd for a firm with market power to distribute its rents for no good reason.

So let’s get the argument straight. Google — a company that is beloved by consumers — charges less than rivals, returns billions to consumers, and is growing slower than Facebook and Amazon is a monopolist. Or at least so say the utilities who are detested by their customers and haven’t had a game changing innovation in decades.

Conclusion

While the title of this article is intended in jest, a rumored antitrust case against Google is not, and neither is the damage to our faith in competition law caused by the use of funny math put forward by firms who would rather use the political process to regulate rivals rather than invest in innovations to beat them.

Antitrust is an incredibly important tool for modern economies — it is one of the most important differentiators between advanced growing economies and corrupt kleptocracies. As Dr. Santiago Levy Algazi has noted, rigorous competition policy “can make the difference between ‘crony capitalism’ and healthy institutions and markets.”47

Indeed, experience has taught us that robust and undistorted competition produces substantial benefits for consumers and society as a whole by promoting growth, spurring innovation, and facilitating the efficient allocation of resources. It has also taught us that competition law and policy is most effective when it focuses exclusively upon competition and consumer welfare rather than attempting to achieve simultaneous goals, some of which may be in conflict with others.

The truth is that when the government is asked to balance competing interests, it must make choices as to the relative importance of various constituencies and interests. This balance is discretionary and inherently a political calculation and therefore is ripe for political interference. As a result, we are all better off when the singular objective is consumer welfare as measured by product quality and price, as evidenced by careful and rigorous econometric analysis, internal documents, and deposition testimony.

But that’s not what we see here. We see an investigation in which guilt is assumed instead of proven. We see an investigation used for fundraising purposes.48 We see dominant incumbents seek to restrain the investments and product innovations of disruptive companies. And we see the use of statistics that would seem to direct the conclusion that we should break up Denny’s before they gobble up the world.

Click here for a PDF version of the article

* The author represents Google and would like to thank Tal M. Elmatad and Koren W. Wong-Ervin for their invaluable comments and review.

1 About Us, Denny’s, https://www.dennys.com/company/about/.

2 Emily Bryson York, Denny’s Grand Slam Giveaways a Hit With 2 Million Diners, AdAge (Feb. 3, 2009) https://adage.com/article/news/denny-s-grand-slam-giveaway-a-hit-2-million-diners/134306; Staff and Wire Reports, ‘This is a Treat’: Denny’s offers Free Grand Slam Breakfasts, ABC (Feb. 3, 2009), https://abcnews.go.com/Business/story?id=6795566&page=1.

3 Rupal Parekh, Why Denny’s Dropped Out of the Super Bowl, AdAge (June 26, 2011) https://adage.com/article/special-report-super-bowl/denny-s-dropped-super-bowl/148511.

4 About Us, Denny’s, https://www.dennys.com/company/about/.

5 Id. Denny’s also has a history of racial discrimination. In the 1990s, Denny’s was sued for systemic discrimination against African Americans, making them pay cover charges to enter, and refusing to serve them meals. In one incident, six black Secret Service agents assigned to President Clinton’s detail were refused service in Annapolis, Maryland, while their white colleagues were seated and served. Denny’s paid $54 million to settle the suit, which at the time was the largest private racial discrimination settlement ever obtained under the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Stephen Labaton, Denny’s Restaurants to Pay $54 Million in Race Bias Suits, NY Times (May 25, 1994) https://www.nytimes.com/1994/05/25/us/denny-s-restaurants-to-pay-54-million-in-race-bias-suits.html.

6 Denny’s Corporation Reports Results for Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2019, Denny’s (Feb. 11, 2020), http://investor.dennys.com/investor-relations/press-releases/press-release-details/2020/Dennys-Corporation-Reports-Results-for-Fourth-Quarter-and-Full-Year-2019/default.aspx.

7 U.S. Franchise Restaurant Sector Outlook, BMO Harris Bank (Jan. 2018) https://commercial.bmoharris.com/media/filer_public/71/f8/71f86672-0bc5-47ad-a8be-db48918fa090/appmediahero_imagebmohb_ffquarterlyreport_0518_v4.pdf; Top 100, Nation’s Restaurant News (June 2017) https://www.jacksonlewis.com/sites/default/files/assets/event-materials/2017-NRN-Top-100-PDF.PDF.

8 Denny’s Return on Capital Employed (Annual): 54.87% for Dec. 31, 2019, YCharts (accessed June 30, 2020), https://ycharts.com/companies/DENN/roce_annual.

9 Online Platforms and Digital Advertising: Market Study Interim Report, UK Competition & Markets Authority, ¶ 59 (Dec. 18, 2019) https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5dfa0580ed915d0933009761/Interim_report.pdf (hereinafter CMA Interim Report); Online Platforms and Digital Advertising, Market Study Final Report, Appendix D, UK Competition & Markets Authority (July 1, 2020) https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5efb1c97e90e075c58556244/Appendix_D_Profitability_of_Google_and_Facebook_non-confidential.pdf; Fiona M. Scott Morton & David C. Dinielli, Roadmap for a Digital Advertising Monopolization Case Against Google, Omidyar Network, p. 14 (May 2020), https://www.omidyar.com/sites/default/files/Roadmap%20for%20a%20Case%20Against%20Google.pdf(hereinafter Roadmap).

10 CMA Interim Report ¶ 2.65 (emphasis added).

11 Id.

12 Roadmap at 14.

13 65 F.3d 1406, 1412 (7th Cir. 1995).

14 Bailey v. Allgas, Inc., 148 F. Supp. 2d 1222, 1245 (N.D. Ala. 2000), aff’d, 284 F.3d 1237 (11th Cir. 2002).

15 Telerate Sys., Inc. v. Caro, 689 F. Supp. 221, 238 (S.D.N.Y. 1988).

16 Phillip E. Areeda & Donald F. Turner, Antitrust Law: An Analysis of Antitrust Principles and Their Application, p. 337 at ¶ 512c (Vol. II 1978).

17 Franklin M. Fisher & John J. McGowan, On the Misuse of Accounting Rates of Return to Infer Monopoly Profits, 73 Am. Econ. Rev. 82 (1983) (hereinafter Fischer).

18 Fisher at 82.

19 Fisher at 83.

20 12 Utilities Pol’y 71, 72 (2004).

21 Paul A. Grout, Competition Law in Telecommunications and its Implications for Common Carriage of Water, 10 Utility Pol’y 137, 138 (2001).

22 Id.

23 Tex. Util. Code Ann. § 36.051 (West).

24 Dennis W. Carlton & Ken Heyer, Extraction vs. Extension: The Basis For Formulating Antitrust Policy Towards Single-Firm Conduct, 4 Compet. Pol’y Int’l 285, 288 (2008), http://economics.mit.edu/files/4058.

25 Josh Constine, House Rep Suggests Converting Google, Facebook, Twitter Into Public Utilities, TechCrunch (July 17, 2018), https://techcrunch.com/2018/07/17/facebook-public-utility/.

26 Comcast was ranked #1 (i.e. worst) in 2017, #1 in 2016, #1 in 2015, and #2 in 2014. Samuel Stebbins et al., Customer Service Hall of Shame, 24/7 Wall St (Aug. 24, 2017), https://247wallst.com/special-report/2017/08/24/customer-service-hall-of-shame-6/5/; Thomas C. Frohlich et al., Customer Service Hall of Shame, 24/7 Wall St (Aug. 23, 2016), https://247wallst.com/special-report/2016/08/23/customer-service-hall-of-shame-4/6/; Michael B. Sauter et al., Customer Service Hall of Shame, 24/7 Wall St (July 27, 2015), https://247wallst.com/investing/2015/07/27/customer-service-hall-of-shame-2/3/; Douglas A. McIntyre et al., Customer Service Hall of Shame, 24/7 Wall St. (July 18, 2014) https://247wallst.com/special-report/2014/07/18/customer-service-hall-of-shame-3/4/.

27 Id.

28 Stephanie Mlot, Comcast Is America’s Most Hated Company, PC MAG (Jan. 12, 2017), https://www.pcmag.com/news/comcast-is-americas-most-hated-company.

29 Samuel Stebbins et al., Customer Service Hall of Shame, 24/7 Wall St (Aug. 24, 2017), https://247wallst.com/special-report/2017/08/24/customer-service-hall-of-shame-6/4/.

30 Benchmarks by Company: Google, American Customer Satisfaction Index, https://www.theacsi.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=149&catid=&Itemid=214&c=Google; Benchmarks by Company: Xfinity (Comcast), American Customer Satisfaction Index, https://www.theacsi.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=149&catid=&Itemid=214&c=Xfinity+%28Comcast%29&i=Internet+Service+Providers; Benchmarks by Company: PG&E, American Customer Satisfaction Index, https://www.theacsi.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=149&catid=&Itemid=214&c=PG%26E; Benchmarks by Company: AT&T Internet, American Customer Satisfaction Index, https://www.theacsi.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=149&catid=&Itemid=214&c=AT%26T+Internet.

31 See, e.g. generally Gordon Tullock, The Welfare Costs of Tariffs, Monopolies, and Theft, 5 W. ECON. J. 224 (1967); W. Kip Viscusi et al., Economics of Regulation and Antitrust, p. 382 (4th ed. 2005).

32 Douglas Clark & Corinne Weir, Google’ US Ad Revenues Drop for the First Time, eMarketer, Inc. (June 22, 2020) https://www.emarketer.com/newsroom/index.php/google-ad-revenues-to-drop-for-the-first-time/.

33 Online Platforms and Digital Advertising, Market Study Final Report, UK Competition & Markets Authority, ¶ 5.373 (July 1, 2020) https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5efc57ed3a6f4023d242ed56/Final_report_1_July_2020_.pdf (hereinafter CMA Final Report).

34 Roadmap at 5, 6.

35 Id. at 6 (“YouTube is a closer substitute to other online audio-visual content services than it is to social media companies such as Facebook that are based around a social graph.”).

36 Online Platforms and Digital Advertising, Market Study Final Report, Appendix R, UK Competition & Markets Authority, ¶ 15 (July 1, 2020) https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5efb22ebe90e075c4e144c59/Appendix_R_-_fees_in_the_adtech_stack.pdf (hereinafter Appendix R).

37 Sissie Hsiao, How Our Display Buying Platforms Share Revenue with Publishers, Google (June 23, 2020), https://blog.google/products/admanager/display-buying-share-revenue-publishers.

38 Appendix R at ¶ 46.

39 Id. at ¶ 11.

40 CMA Final Report at ¶ 5.242.

41 Roadmap at 3.

42 Douglas Clark & Corinne Weir, Google’ US Ad Revenues Drop for the First Time, eMarketer Inc. (June 22, 2020) https://www.emarketer.com/newsroom/index.php/google-ad-revenues-to-drop-for-the-first-time/.

43 Roadmap at 2.

44 Garett Sloane, YouTube Ad Revenue Disclosed by Google For the First Time, Topped $15 Billion in 2019, AdAge (Feb. 3, 2020), https://adage.com/article/digital/youtube-ad-revenue-disclosed-google-first-time-topped-15-billion-2019/2233811 (“‘We pay out a majority of our revenue to our creators,’ said Ruth Porat, Alphabet’s chief financial officer, speaking during a call with Wall Street analysts on Monday. YouTube splits ad revenue with the publishers and independent video makers. Google keeps 45 percent of the revenue from the ads shown in the videos, according to its terms of service.”).

45 Rachel Kaser, YouTube Claims to Share Billions in Ad Money with Creators, Unlike Instagram, Next Web (Feb. 5, 2020), https://thenextweb.com/facebook/2020/02/05/youtube-claims-share-billions-ad-money-creators-unlike-instagram/.

46 Sarah Frier & Nico Grant, Instagram Brings In More Than a Quarter of Facebook Sales, Bloomberg (Feb. 4, 2020), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-02-04/instagram-generates-more-than-a-quarter-of-facebook-s-sales; Ashley Carman, Instagram Will Share Revenue With Creators For The First Time Through Ads In IGTV, Verge (May 27, 2020) https://www.theverge.com/2020/5/27/21271009/instagram-ads-igtv-live-badges-test-update-creators.

47 Antitrust in Emerging and Developing Countries, Concurrences: Competition Laws Journal and NYU Law (Oct. 24, 2014), https://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/upload_documents/conference%20summary.pdf.

48 Casey Newton, The Antitrust Case Against Google is Becoming Just Another Partisan Fight, Verge (May 20, 2020), https://www.theverge.com/interface/2020/5/20/21263782/google-antitrust-case-attorneys-general-justice-partisan-politics.