By Frank JIANG, John JIANG (Zhong Lun Law Firm)1

Introduction

As a participant in the global economy, and in response to current delicate global trade and geopolitical situations, China is making increasing efforts to encourage investment in innovation. One of China’s initiatives relates to the intersection of IPR licensing and antitrust, with China growing its antirust regulatory teeth to become one of the leading jurisdictions taking initiatives to foster an innovation-driven economy. China is learning the art of balancing IPR protection and antitrust regulation in a “glocal” battleground. China’s activities, as described below, may shed some light on such emerging trends:

- Legislation. A special Anti-monopoly Guidelines on Abuse of Intellectual Property Rights (“AML Guidelines on IPR (Draft)”) is in the process of formalization.

- Enforcement. A super-agency – the State Administration for Market Regulation (“SAMR”) was created in 2018 to consolidate antitrust and IPR enforcement functions, and technology-intensive industries have become one of the antitrust enforcement priorities.

- Judiciary. The Supreme People’s Court (“SPC”) established a special IP appellate tribunal in 2019 to hear the appeals of IP and antitrust cases and, at its discretion, high profile and complicated first-instance trials. Local courts are also aspiring to address new emerging antitrust/IPR related issues.

The Anti-monopoly Law (“AML”) does not apply to lawful exercise of intellectual property rights, but prohibits abuse of IPRs to eliminate or restrict competition. Accordingly, for antitrust compliance, it is key to assess the competitive effect of the relevant conduct and mergers which involve IPRs. In China, the starting point for such competition analysis is delineating a relevant market (from both a product and geographic perspective). Where IPRs are involved, factors such as innovation, R&D, protection period and the “territoriality” of IPRs may impact the market definition.

Below are some key highlights of Chinese enforcement and judicial practices with respect to IPR licensing in China, from the perspectives of merger control, joint conduct and unilateral conduct.

1. Merger Control

IPR licensing plays its role in China’s merger control regime mainly in terms of competition assessment, and imposition of merger remedies, etc. For example, in competition assessment, IPRs could be deemed to be a significant market entry barrier (see, e.g. Merck/AZ Electronic and Nokia/Alcatel-Lucent). IPRs could also become a key element in remedies to conditionally clear a merger, either in the form of structural remedies (see, e.g. Baxter/Gambro and Panasonic/Sanyo) or behavioral remedies (see, e.g. Thermo Fisher/Life Technologies, Google/Motorola, and Bayer/Monsanto).

2. Joint Conduct

An IPR license arrangement could raise cartel or vertical concerns. Competing IPR holders may engage in conduct such as price fixing, production/sales volume restriction, market allocation, new technology restriction, or boycotts. Standardization processes or patent pools may also breed cartel concerns. An IPR licensor could also impose resale price maintenance terms on a licensee. Also, we have seen instances of IPR holders exclusively licensing their technology to their Chinese joint ventures. The interaction between the licensor and its Chinese joint venture, e.g. in attempting to achieve consistent pricing strategy, may raise horizontal and/or vertical concerns.

3. Unilateral Conduct

Under the AML, unilateral conducts (more often referred to as abuses of dominance) include excessive pricing, predatory pricing, refusal to deal, exclusive dealing, tying and imposing unreasonable trade terms, and discriminatory treatment. Finding abusive conduct generally follows a four-step approach: dominance, abusive conduct (restrictive conduct), a lack of justification, and effects (an anti-competitive impact). We will discuss below some typical instances of IPR-related abusive conduct, with more detail forthcoming in the next issue.

Excessive royalties

Excessive royalties might be assessed by looking at the costs and the value of the IPR, and pricing for comparable licenses. Assessment of costs can take into account whether an IPR holder has assumed the risk of making significant R&D investments without the guarantee of success in commercializing any resulting products. For standardization activities, there is additional technical risk as to whether the developed technology can be incorporated into the standard, and whether the standard can be widely adopted.

In adopting the comparable license approach, “comparability” is a key factor. In addition, the “top-down” approach adopted in TCL v. Ericsson2 (vacated in part, reversed in part and remanded during appeal) and other SEP disputes in the U.S. also has implications in China. We have learnt that in complex cases the court may cross-check fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (“FRAND”) terms based on different approaches.

“Justifiable cause” used to not be available as a specific defense against unfair pricing allegations. However, newly-issued AML implementing rules appear to provide room for a dominant firm to defend against alleged “unfair” pricing by factoring in additional criteria.

Refusal to license

Where an undertaking has a dominant market position, especially when it holds SEPs or its IPR is found to constitute an “essential facility” for production and business operations, refusal to license its IPR without justifiable causes may constitute an abuse of dominance. The plaintiffs’ allegation of market dominance for possessing an essential patent portfolio and invocation of the “essential facility” doctrine in Hitachi Metals Case has attracted significant attention. While denying access to an essential facility creates heightened exposure to refusal to license allegations, the new AML implementing rules also call for a more nuanced evaluation.

Tying

Tying arrangements in an IPR license could take the form of tying another IPR (e.g. tying of SEPs and non-SEPs) or tying another physical product while licensing the IPR. Finding illegal tying in connection with IPR licensing generally follows the same analytical framework regarding tying of physical products. One key factor is to assess whether the licensed IPR and the tied IPR/product are separate products, whether the licensee has been required to accept the tied IPR/product against its will, and whether a tie’s efficiency cannot outweigh the possible anticompetitive effect.

Imposing questionable license terms (including exclusive terms)

The imposition of exclusive and other pro-licensor terms by a dominant IPR holder may trigger antitrust concerns in terms of the imposition of unreasonable contractual terms or excessive pricing allegations. For SEP holders, being held-out by implementers that do not engage in good-faith license negotiations and/or withhold royalty payments, Qualcomm v. Meizu and InterDigital v. Huawei (a patent infringement action recently filed by InterDigital against Huawei seeking, among other things, a determination of FRAND terms for SEP license) provides meaningful guidance.3

I. The Intersection of IPR Licensing and Antitrust in China: A Balancing Act

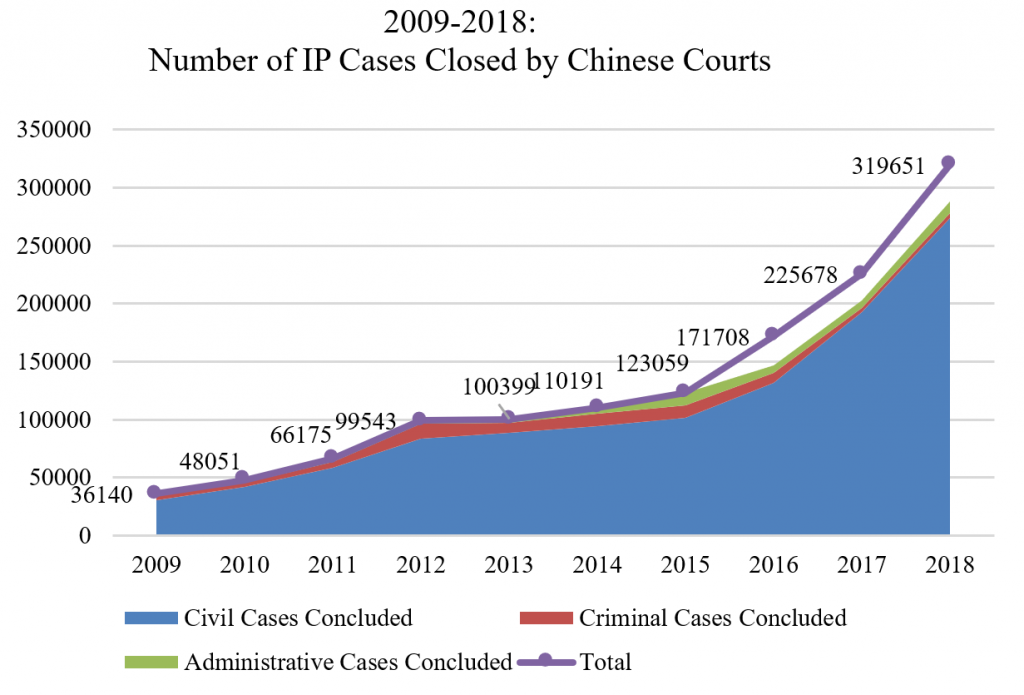

As the largest marketplace worldwide and in response to the current delicate global trade conditions, China is striving to upgrade its economy to an innovation-oriented model by attracting foreign investments and encouraging indigenous innovation in IPR intensive sectors. For example, the new Foreign Investment Law (“FIL”) promulgated in March 2019 (and entering into effect on January 1, 2020), its implementing rules and associated policies emphasize that China will protect the IPR of foreign investors and foreign investors in China, and encourage technological cooperation based on fair and equal terms.4 Shortly after the promulgation of the FIL, the Chinese government announced amendments to its joint venture law and the Regulations on Administration of Technology Import and Export (“TIER”), to loosen restrictions on cross-border technology transfers and offer more flexibility for negotiation of certain terms. These include the requirement that a foreign licensor be obligated to indemnify Chinese licensees for any loss arising from the use of licensed technologies, the requirement that any improvements made by a Chinese licensee to an imported technology must per se belong to the licensee, and the provision requiring that certain restrictive clauses imposed by foreign licensors are invalid5. As shown in the chart below, the number of IPR disputes tried by Chinese courts has also increased in the past decade, especially in the last five years.

(Source: Publicly available information of SPC statistics)

The “glocal” dynamic is also reflected in antitrust enforcement concerning IPRs. Since the Anti-monopoly Law (“AML”) took effect in 2008, China has shown its growing regulatory teeth in terms of antitrust enforcement, becoming more confident to conduct independent and China-specific investigations in high profile and complex global cases. On the other hand, the Chinese antitrust authority is also striking a balance between antitrust regulation and IPR protection, and has been taking a more prudent stance.

The following developments in IPR-related antitrust legislation, enforcement and judicial activities sheds some light on these emerging trends.

a. Legislation. Similar to the EU and the U.S., which have specific guidelines with respect to antitrust regulation of technology transfers and IPRs, China is also in the process of formulating a special AML Guidelines on IPR (Draft), amid existing IPR-related provisions in the AML and several other implementing rules.

b. Enforcement. A super-agency – the State Administration for Market Regulation (“SAMR”) was created in last year’s government reshuffle program to consolidate not only the antitrust enforcement functions of State Administration for Industry and Commerce (“SAIC”), National Development and Reform Commission (“NDRC”) and Ministry of Commerce (“MOFCOM”), but also a number of other responsibilities concerning patents, trademarks and geographical indications, by housing the State Intellectual Property Office (“SIPO,” now called China National Intellectual Property Administration, “CNIPA”) and some other agencies under the same roof.

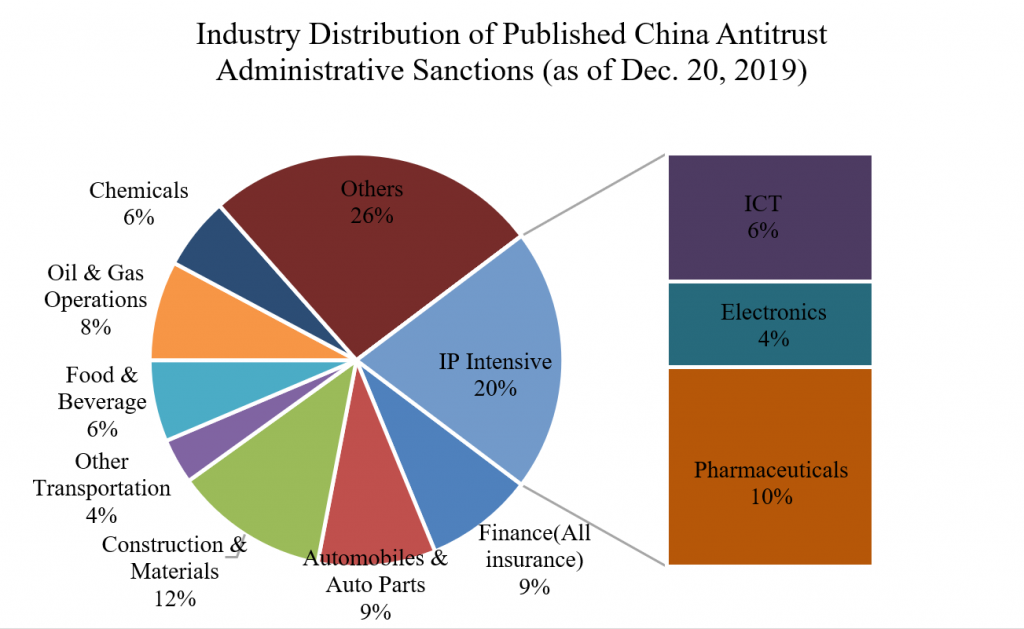

IP-intensive industries have become one of China’s antitrust enforcement priorities. Enforcement in IPR-intensive sectors and some highlighted cases is illustrated below:

(Source: Publicly available information of NDRC, SAIC and SAMR cases)

(Source: Publicly available information of NDRC, SAIC and SAMR cases)

c. Judiciary. As indicated above, Chinese courts have accumulated rich experience in adjudicating IP-related disputes, with increasing numbers of IP cases being brought before courts in recent years. At the beginning of this year, the Supreme People’s Court (“SPC”) established a special IP appellate tribunal to hear appeals against first-instance decisions and rulings in patent and antitrust disputes and to hear, at its discretion, first-instance trials over such disputes when they involve highly important and complicated nationwide matters. The IP tribunal is expected to centralize jurisdiction, leveraging more professional resources in IP/antitrust disputes and to improve the consistency of decisions.

Local courts are also aspiring to address new emerging antitrust/IP related issues, with the Guangdong and Beijing courts being especially active. In April 2018, the Guangdong High People’s Court (“GHC”) issued a working guide on adjudicating cases concerning SEP disputes (“GHC Guide”), with comprehensive coverage of SEP-related issues, including approach to finding SEP infringement, injunctive relief, determination of FRAND license terms, and SEP-related anti-monopoly claims. In September 2018, the Beijing High People’s Court (“BHC”) issued the Opinions of the Beijing High People’s Court on Enhancing the Adjudication of IPR Cases and Promoting Innovation and Development (“BHC Opinions”), which includes principles on adjudication of SEP related cases and monopoly cases.

In addition to these domestic efforts, China is actively participating in international cooperation on antitrust legislation and enforcement. China has entered into a memorandum of understanding (or a similar arrangement) with a number of countries or regions, including the U.S., the EU, Japan and South Africa. For example, on October 15, 2015, MOFCOM and the European Commission concluded a best practices framework for cooperation in reviewing mergers, marking growing cooperation between regulators handling multinational transactions, and. further, in April 2019 signed the Framework Agreement on Competition Policy Dialogue between China and the EU and another competition cooperation MoU.6/sup>

Against this backdrop, we will provide an overview of China’s antitrust regulation on merger control, joint conduct and unilateral conduct in the context of global IPR licensing. We will highlight the antitrust pitfalls that companies should watch out for, as well as possible defenses against alleged AML violations.

II. Analytical Framework for IPR Related Conduct

As IPRs, by their very nature, concern a legitimate right to exclude competitors, IPR licensing arrangements generally enhance competition. Under Article 55 of the AML, the AML does not apply to lawful exercise of intellectual property rights, but abuse of IPRs to eliminate or restrict competition is regulated.7

With Article 55 of the AML being the legal basis, Article 2 of the AML Guidelines on IPR (Draft) further sets forth the following analytical principles for IPR related conduct: (i) adopt the same regulatory standard as those applicable to other property rights and follow the basic analytical framework under the AML; (ii) take into account the characteristics of IPR; (iii) do not presume that an undertaking has a dominant market position in the relevant market due to its IPRs; and (iv) take into account the positive impacts of the relevant conduct on competition and innovation on a case-by-case basis.

Accordingly, for antitrust compliance, it is key to assess the competitive effect of conduct and mergers which involve the exercise of IPRs, such as licensing. In other words, it is particularly important to assess the positive impacts of IPR-related conduct on innovation and efficiency (including promoting the dissemination and utilization of technologies, enhancing the utilization efficiency of resources, etc.).8

III. Starting Point – Defining the Relevant Market

Any competition analysis (such as identification of competitors, assessment of market power, competitive effects) is carried out within a “relevant market.” Therefore, the starting point of any such analysis with respect to merger control, unilateral conduct or joint conduct is delineating a relevant market (from product and geographic dimensions).

Where IPRs are involved, factors such as innovation, R&D, protection period and the “territoriality” of IPRs may impact the market definition. For example, in Thermo Fisher/Life Technologies,9 for certain products that were highly technology-intensive or have proprietary patents, and where the global market relies on large suppliers, the relevant geographic market was defined to be worldwide; for the remaining products that involved less complicated production technologies and no proprietary patents, and could be produced by either domestic or foreign suppliers, the relevant geographic market was defined at the China level.

In addition, certain technologies may be defined to constitute a standalone market in technology transfer or licensing arrangements. Subject to a substitutability analysis, the relevant technology market may not necessarily be the same as the specific technology covered by the licensed IPR. In determining whether a given technology is substitutable for the technology embodied in a certain IPR, one may need to take into account not only its field of use but also potential fields of use.10 Despite the lack of clear-cut guidance or practice, the option of defining a relevant technology market does offer more flexibility for both the IPR holder and enforcement agencies to conduct more meaningful competition analysis.

For the licensing of standard essential patents (“SEPs”), recent enforcement and judicial practice (such as Huawei v. InterDigital and NDRC Investigation into Qualcomm) tends to define the license of an individual SEP as a separate product market. As such, an SEP is unique and non-substitutable, and the relevant geographic market is taken to be as a particular country or region, because the issuance, use and protection of patents are territorial in nature. Accordingly, for a portfolio license, the relevant market has been defined as a set of separately formed relevant product markets for the licensing of each SEP and the relevant geographic market would also be the set of the national or regional markets at issue. However, this approach is not followed in every case.11 It may also be worthwhile to explore some novel alternative approaches, yet to be tested in practice, such as a market of technologies enabling certain functionality, a market of different generations of communication standards, or a market of wireless public network communication methods.

Definition of markets involving essential facilities have some similarities to SEP licensing markets. In the antitrust dispute between four Chinese rare earth companies and Hitachi Metals (the “Hitachi Metals Case”), the plaintiffs accused Hitachi Metals of refusing to license patents that were essential, non-substitutable and inevitable for the plaintiffs’ production (even though such patents are not SEPs). The plaintiffs argued that the relevant market should be defined as the market for essential patents for sintered NdFeB magnets in an attempt to invoke the “essential facility” doctrine.12

While defining a relevant market may not be necessary or essential for conducting a competition analysis in every case as it is in some jurisdictions, in China, as noted, the relevant guidelines generally take market definition as the starting point for analyzing any given conduct, and as an important step in antitrust enforcement,13 regardless whether it is IPR-related or not.

IV. Merger Control

IPR licensing plays a role in China’s merger control regime in several contexts.

Firstly, an IPR license in and of itself might constitute a transaction that triggers a merger filing. Where the license of an IPR constitutes a stand-alone business, gaining control over the IPR may constitute a concentration. In accordance with the AML Guidelines on IPR (Draft), in addition to the transfer of IPR, such control can also be gained through an exclusive license arrangement, depending on the term of such license.

More importantly, IPR licenses can impact competitive assessments, and the imposition of remedies.

In assessing the competition impact of a concentration, the Chinese antitrust authority usually takes into account the market share and market power of relevant undertakings, the level of concentration in the relevant market, the impact on market entry and technology progress, the impact on consumers and other undertakings, and the impact on the national economy.14 The IPR factor mainly plays a part in the market entry factor, and the reliance by consumers or other undertakings. For example, in Merck/AZ Electronic,15 MOFCOM considered that some patents held by Merck constituted substantial barriers for new entrants to enter the relevant market, thereby strengthening Merck’s market power and the merger may have adverse competition impact. Similarly, in Nokia/Alcatel-Lucent,16 MOFCOM considered communication SEPs to be the major obstacle to entry in the downstream market, as licensees were highly reliant on access to communication SEPs.

IPRs may also play a part in any remedies imposed on the concentrations that are deemed to be likely to have adverse competitive impact. These can be structural, behavioral or hybrid in nature.

a. As a structural condition, IPRs and research facilities may form part of a divestiture or as a supporting condition for securing an effective divestiture. For example, in Baxter/Gambro AB,17 some IPRs and know-how owned by Baxter were required to be divested in order to clear the case; in the Panasonic/Sanyo,18 Panasonic was required to license relevant IPRs to the purchaser when divesting certain business.

b. Behavioral conditions involving IPRs may take a variety of forms, including supply commitments (granting access to a license consistent with current practice, see, e.g. Thermo Fisher/Life Technologies and Google/Motorola19), non-discrimination (license relevant IPRs on non-discriminatory terms, sometimes on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms, see, e.g. Bayer/Monsanto20), reporting obligations (reporting on the execution of a license agreement to the antitrust authority, see, e.g. Merck/AZ), etc. The Chinese antitrust authority may use the term FRAND in connection with a behavioral remedy both in cases that involve IPRs and others. But it is noteworthy that the meaning of “FRAND” in this context is different from that in the SEP licensing context. Here it relates to the requirements under the AML, covering instances such as imposing unreasonable additional transaction terms in the course of a transaction and discriminating among trade counterparties under the same conditions in respect of transaction terms, such as pricing, etc.

V. Joint Conduct

An IPR license arrangement could raise cartel or vertical concerns. The assessment of vertical or horizontal restraints in an IPR license arrangement is similar to the assessment of such restraints in other types of agreements.

Competing IPR holders may engage in conduct such as price fixing, production/sales volume restriction, market allocation, new technology restriction, or boycotts. Such conduct is viewed as per se illegal and the relevant AML rules do not appear to require a stand-alone effects analysis to find a violation. Among these, price fixing, production/sales volume restrictions, and market allocation will be viewed as extremely “hard-core” cartels.21 Close cooperation among competitors during standardization or in patent pools may also breed cartel concerns – patent pools may also provide a forum for a dominant undertaking to engage in abusive conduct.22 On the other hand, implementers might also jointly boycott against a common licensor.

A license agreement is typically seen as a vertical relationship between a licensor and licensee, though it may also sometimes have a horizontal component when the licensor and the licensee, or licensees themselves are actual or potential competitors in a relevant market. A horizontal restraint on competitors in a licensing arrangement does not necessarily raise antitrust concerns. Vertically, an IPR licensor could also impose resale price maintenance (“RPM”) terms on a licensee. In China’s administrative enforcement practice, RPM is viewed as per se illegal and the relevant AML implementing rules do not appear to require a stand-alone effects analysis to find a violation. However, there remains an unresolved tension with judicial practice, as Chinese courts have adopted a rule of reason approach in reviewing vertical restraints (that the SPC attempted to harmonize in its recent ruling on Yutai RPM Case).23

In practice, we have seen a number of cases where a global licensor, as a strategic arrangement for China, decides to establish a joint venture in China and exclusively license its technology to the joint venture for use and sublicense it to Chinese licensees. It is possible that the licensor may wish to achieve a consistent pricing strategy with respect to Chinese licensees. There are both horizontal and vertical components in any such arrangement. From a horizontal perspective, while the licensor and the China JV may not actually compete with each other, there is still uncertainty as to whether the regulator may regard such a strategy as akin to market allocation or another unlawful monopoly agreement, in particular if the licensor and China JV share any common customer(s), although it may be argued that the international parent company, its JV partner and the JV are not competitors in the traditional sense if the JV partner has no competing technology to contribute to the JV, and the JV itself is not developing a competing technology. From a vertical perspective, as the licensor and the China JV should have no visibility of each other’s customer pricing as a matter of principle, if pricing constraints are imposed on the JV, there could be a higher risk of a finding of RPM.

Click here for a PDF version of this article

1 Frank Jiang is an equity partner at Zhong Lun. Frank specializes in antitrust and M&A, with a particular interest in the intersection of law and technology. He acted as a lead competition counsel in a number of high-profile investigations/ litigations, and has worked on numerous antitrust, corporate and commercial matters in a variety of innovation industries, including aerospace, automobile, chemistry, engineering, ICT, etc. John Jiang is a senior counsel at Zhong Lun. John has over twenty years of experiences of serving multinationals. His expertise is especially sought by clients for PRC merger control issues in connection with M&A transactions, as well as unilateral conduct and joint conduct. His practice covers antitrust, merger and acquisition, market entry strategy, alliance/outsourcing, and technology licensing. This paper was firstly prepared for a panel discussion on “Global Licensing – How to Avoid Antitrust Pitfalls” during the 2019 annual conference of American Intellectual Property Law Association (AIPLA). Emily Xu, Elemy Yuan and Nicole Yu, members of Zhong Lun’s antitrust practice group, contributed to this paper. A debt of gratitude is also owed to Richard Stark and Dina Kallay for their helpful comments.

2 The first instance was ruled by Judge James V. Selna on March 9, 2018 (No. 8:14-cv-00341-JVS-DFM, the United States District Court for the Central District of California). On December 5, 2019, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit vacated in part, reversed in part the district court decision for depriving Ericsson of the right of jury trial and remanded the case for further proceedings, leaving the top-down approach still pending future judiciary examination at the lower court (2018-1363, 2018-1732).

3 Relatedly, on December 19, 2019, the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and the U.S. Department of Justice, Antitrust Division (DOJ) issued a joint policy Statement recognizing that when licensing negotiations fail, “appropriate remedies” for patent infringement, including injunctive relief, should be available to SEP holders. This Statement follows the DOJ’s withdrawal from the 2013 SEP policy statement, which had been construed incorrectly as suggesting that special remedies applied to SEPs and that seeking an injunction or exclusion order would harm innovation and dynamic competition.

4 Article 22 of the FIL: The State protects the intellectual property rights of foreign investors and foreign-invested enterprises, and protects the legitimate rights and interests of holders of intellectual property rights and relevant right holders; any infringement of intellectual property right shall be strictly subject to legal liability in accordance with the law.

In the course of foreign investment, the State encourages technology cooperation on the basis of voluntariness and commercial norms. Conditions for technology cooperation shall be determined by all investing parties upon negotiation on the basis of equality in accordance with the principal of fairness. Administrative departments and their staff may not use any administrative means to force the transfer of technology.

China is also formulating the Regulation on the Implementation of the FIL. In the latest draft for comments, it is provided that the State establishes the punitive compensation system for intellectual property infringement, promotes the establishment of rapid coordinated protection mechanism for intellectual property, improves the diversified dispute resolution mechanism for intellectual property dispute and the aid system for defending intellectual property, and enhances the protection of intellectual property of the foreign investors and the FIEs.

In the formulation of standards, the intellectual property of the foreign investors and the FIEs shall be equally protected in accordance with the law; if the patents of the foreign investors and the FIEs are involved, the relevant administration regulations about the patents in the national standards shall apply.”

In the Opinion of the State Council on Better Utilizing Foreign Capital issued in early November 2019, it further emphasizes the significant role of courts in IPR protection and requires to improve the IPR protection systems, including the arbitration, mediation and diversified dispute resolution mechanism, etc.

5 Pursuant to the updated TIER, parties may independently agree on indemnity provisions and the ownership of improvements made by the licensees. Cross license, royalty free license or joint ownership should be allowed. Notably, although the provision regarding certain restrictive clauses is removed from the TIER, theses clauses are prohibited under the PRC Contract Law and relevant judicial interpretations for any and all licensors, and its implication is pending further observation.

6 See, e.g. http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ae/ai/201601/20160101235053.shtml; http://mt.cicn.com.cn/index.php?s=/Wap/Article/detail/id/301229/page/; https://competitionlawchina.com/2019/04/11/agency-cooperation-with-the-eu/.

7 Article 55 of the AML specifically provides that: “[t]his Law shall not apply to the exercise of its intellectual property rights by an undertaking in accordance with the relevant provisions of intellectual property laws or administrative regulations; provided that this Law shall apply to any conduct of an undertaking whereby intellectual property rights are abused to eliminate or restrict competition”.

8 For example, Article 25 of the GHC Guide provides that in adjudicating cases concerning SEP related monopoly disputes, the court shall follow the basic approaches including assess the effect of the relevant conducts on market competition, with a focus on the impact of the conducts on innovation, efficiency and consumer welfare, on a case-by-case basis. Consistent with the GHC Guide, the BHC Opinions provide that competition harm analysis shall be based on the competition effect, including the impact of the conduct concerned on promoting competition and improving efficiency.

9 Public Announcement Concerning Anti-Monopoly Review Decisions on Conditional Approval of Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.’s Acquisition of Life Technologies Corporation, January 14, 2014, Chinese text available at http://fldj.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx/201401/20140100461603.shtml.

10 Article 3 of the AML Guidelines on IPR (Draft): Where it is difficult to comprehensively assess the competition effect of the exercise of IPR by merely defining the relevant product market, the definition of the relevant technology market may need to be introduced. In light of the situation of a specific case, the effect on factors such as innovation and R&D can also be taken into account…The relevant technology market refers to a market that consists of a group or a class of technologies which are fairly closely substitutable as deemed by users…When determining whether certain technology is substitutable to the technology involved in the IPR, we not only need to take into account the current practice field, but also the potential practice fields.

11 Some SEP owners have argued that the relevant market should be defined as the license of the collective technologies covered by certain standard(s), instead of a single SEP (see Huawei vs InterDigital before GHC); in addition, in Nokia/Alcatel-Lucent, MOFCOM also accepted the market definition of the license of the collective communication SEPs and assessed Nokia’s market power mainly based on the proportion of its SEPs against the overall SEPs covered by the 2G and 3G standards.

12 Marks & Clerk, “China: Hitachi Metals Involved In Chinese Case On Abuse Of Non-Essential Patents”, available at http://www.mondaq.com/x/498274/Patent/Hitachi+Metals+Involved+In+Chinese+Case+On+Abuse+Of+NonEssential+Patents.

13 Article 2 of State Council Anti-monopoly Commission Guidelines for Definition of Relevant Market (24 May 2009): The scientific and sensible definition of a relevant market is of significant relevance for critical issues such as identifying competitors and potential competitors; determining both an undertaking’s market share and the degree of market concentration; finding an undertaking’s market position; analyzing the impact of an undertaking’s conduct on market competition; and determining the whether an undertaking’s conduct is illegal, and if so, the legal liabilities to be assumed. Therefore, the definition of the relevant market is generally the starting point for analyzing a competitive conduct, and an important step in anti-monopoly law enforcement.

14 Article 27 of the AML: The following factors shall be taken into account in reviewing the concentration of undertakings:

(i) the market shares of the participating undertakings in the relevant market and their market power;

(ii) the level of concentration in the relevant market;

(iii) the impact of the concentration of undertakings on market entry and technology progress;

(iv) the impact of the concentration of undertakings on consumers and other relevant undertakings;

(v) the impact of the concentration of undertakings on the national economic development; and

(vi) other factors affecting competition in the market which are to be considered, as determined by the competent State Council Anti-monopoly Enforcement Authority.

15 Public Announcement Concerning Merger Control Review Decisions on Conditional Approval of Merck KGAA’s Acquisition of AZ Electronic Materials S.A., April 30, 2014, Chinese text available at http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/b/e/201404/20140400569107.shtml.

16 Public Announcement Concerning Merger Control Review Decisions on Conditional Approval of Nokia’s Acquisition of Alcatel-Lucent, October 19, 2015, Chinese text available at http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/b/c/201510/20151001139748.shtml.

17 Public Announcement Concerning Merger Control Review Decisions on Conditional Approval of Baxter International Inc.’s Acquisition of Gambro AB, August 8, 2013, Chinese text available at http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/b/e/201308/20130800244249.shtml.

18 Public Announcement Concerning Merger Control Review Decisions on Conditional Approval of Panasonic’s Acquisition of Sanyo, October 30, 2009, Chinese text available at http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/b/c/200910/20091006593293.html.

19 Public Announcement Concerning Merger Control Review Decisions on Conditional Approval of Google’s Acquisition of Motorola Mobility, May 19, 2012, Chinese text available at http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/b/c/201205/20120508134325.html.

20 Public Announcement Concerning Merger Control Review Decisions on Conditional Approval of Bayer’s Acquisition of Monsanto, March 13, 2018, Chinese text available at http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/b/e/201803/20180302719125.shtml.

21 Article 22 of the Interim Rules on Prohibition Against Monopoly Agreements published by SAMR on June 26, 2019: Based on the application for suspending investigation submitted by the subject undertaking, the anti-monopoly enforcement authority shall decide whether or not to suspend the investigation, taking into consideration the nature, duration, consequence, social impact of the suspected monopolistic conduct, and the committed remedial measures and expected effect thereof, etc.

An anti-monopoly enforcement authority shall not accept any application for suspending investigation regarding a suspected monopoly agreement which falls into any category under Article 7 through Article 9 (price fixing, production/sales volume restriction, market allocation) of these Rules.

22 Article 25 of the AML Guidelines on IPR (Draft).

23 Chinese top court dismisses local fish feed firm’s RPM retrial application, available at https://app.parr-global.com/intelligence/view/prime-2858878; ZHONG Chun, The Administrative and Judicial Criteria in Assessing Resale Price Maintenance: Interpretation of Supreme People’s Dismissal of Yutai’s Retrial Application, July 17, 2019, Chinese text available at http://www.sohu.com/a/327178325_742371.