By Elizabeth Wang, Kun Huang, Sophie Yang & Aston Zhong1

By Elizabeth Wang, Kun Huang, Sophie Yang & Aston Zhong1

Question 1: The Chinese competition authority just issued its 2020 annual report, which provides a review of antitrust enforcement in the last five years. What are the key takeaways on the caseload and processing times on merger transactions?

In early September of 2021, China’s competition authority, the State Administration for Market Regulation (“SAMR”) issued a report (“SAMR 2020 Report”) summarizing its Anti-Monopoly Law enforcement activities during the period covering the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020).2 From 2016 to 2020, SAMR concluded 2,147 merger reviews and completed 179 antitrust investigations, imposing fines totaling RMB 2.79 billion (or USD 413 million3). The SAMR 2020 Report also examined the competitive landscape and highlighted potential concerns in nine key industries (i.e. pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, automotive, construction materials, transportation, petrochemicals, steel, internet, and public services). Lastly, it provided updates on various legislations, including the amendment of the Anti-Monopoly Law, the introduction of amended regulations,4 and six guidelines covering multiple industries and topics (i.e. Automotive,5 IP,6 Platform Economy,7 Commitments,8 the Application of Leniency,9 and Compliance10). Below, we identify several trends observed in merger-related caseloads and processing times in China.

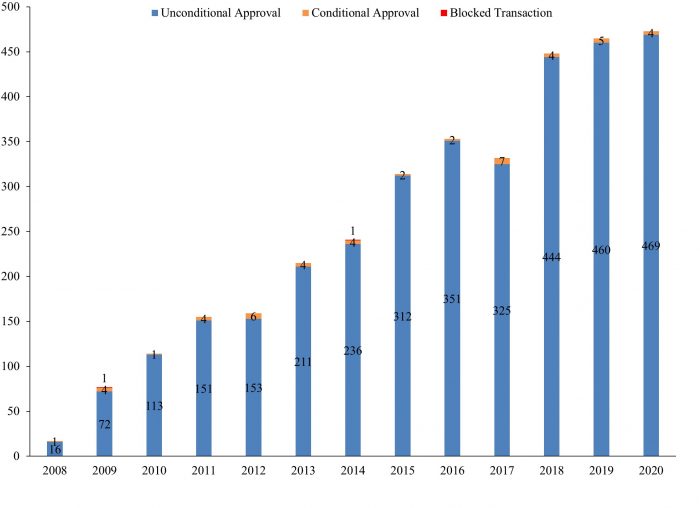

First, the number of transactions reviewed11 in China has continued to increase, and the number of unconditional clearances has remained high. As shown in Figure 1-1 below, the number of transactions has increased every year since China enacted the Anti-Monopoly Law in 2008, with the only exception being 2017. The COVID-19 pandemic did not slow the number of cases subject to SAMR’s review – a total of 473 mergers were reviewed in 2020, an all-time high. Mergers between domestic companies significantly increased in the past three years and surpassed the number of mergers involving foreign entities for the first time.12 At the same time, the unconditional approval rate remains high – 98 percent of cases were approved unconditionally, with only 48 cases approved with remedies and two cases blocked between 2008 and 2020, averaging four interventions each year.

Figure 1-1 Number of Concluded Cases, 2008-202013

Source: SAMR and MOFCOM decisions, summarized by Compass Lexecon

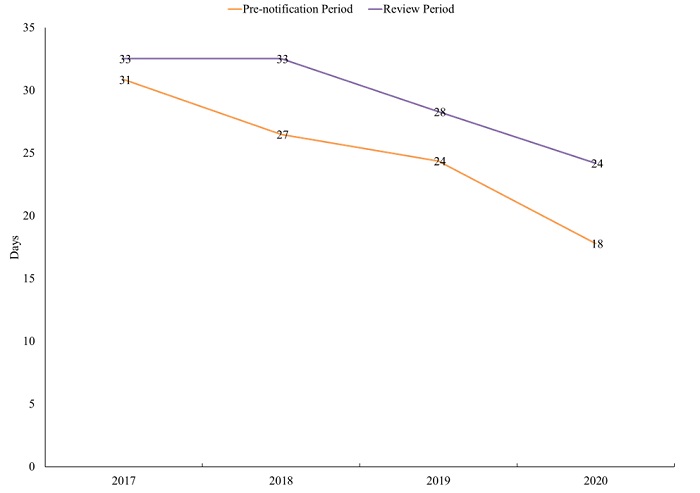

Second, review time has decreased significantly over time in China. According to the SAMR 2020 Report, the average time from case acceptance to review completion is 24.2 days among all transactions reviewed by SAMR between 2016 and 2020, a significant improvement from 41.2 days between 2011 and 2015.14 There is also a reduction in the pre-notification period between the notification and acceptance dates. The average pre-notification period was 17.8 days between 2016 and 2020 compared to 40.8 days between 2011 and 2015.15 These reductions are partially due to the introduction of the simple case procedure in 2014 to handle transactions deemed less likely to result in competition issues (e.g. those involving parties with lower market shares or revenues in China and thus are eligible for an expedited review process).16 Between 2016 and 2020, over 70 percent of cases in China were reviewed under the simple case procedure.17

Figure 1-2 Pre-notification and Review Period, 2017-202018

Source: SAMR 2019 and 2020 Reports19

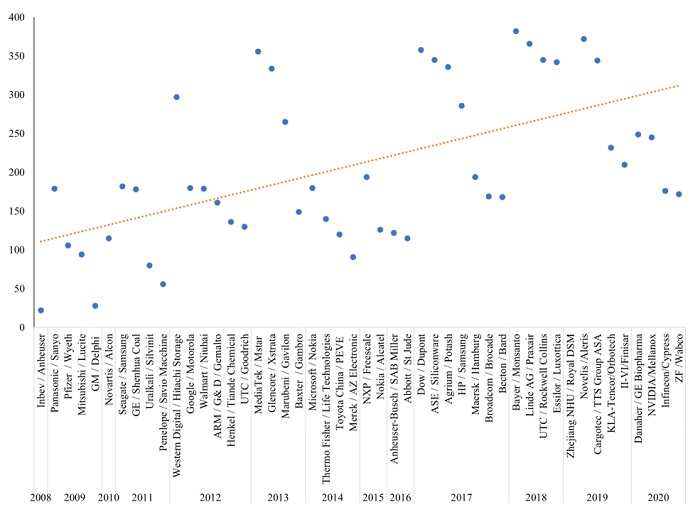

Third, on intervention cases, it still takes SAMR a substantial amount of time to conduct its reviews. Figure 1-3 shows the review time and trend line for complex cases where SAMR intervened from 2008 to 2020. Over time, the average review time for intervention cases has increased. For the 22 intervention cases from the last five years, the average review time was 276 days (excluding the pre-notification period before a case is officially accepted by SAMR). When SAMR decides to intervene in a transaction, the review will usually progress into the second or third phase. SAMR is mandated to reach a decision within 180 days after the case is accepted. However, when no resolution is reached within that period, the filing can be withdrawn and refiled, thus resulting in a longer review time. Between 2016 and 2020, 16 out of 22 intervention cases went through the “pull-and-refile” procedure to allow SAMR more time to review the case.

Figure 1-3 Review Periods of Intervention Cases, 2008-2020 Source: SAMR and MOFCOM decisions, summarized by Compass Lexecon20

Source: SAMR and MOFCOM decisions, summarized by Compass Lexecon20

Question 2: There have been many high-profile semiconductor mergers in the last few years. Can you highlight the trends in China’s reviews of semiconductor transactions? Is China paying more attention to certain theories of harm for these transactions?

Semiconductors are essential components in many important industries such as communications, computing, transportation, and clean energy. The global semiconductor industry has recently experienced significant consolidation. In the last five years alone, there have been 72 merger reviews completed in China for semiconductor-related transactions.21 We observe three key trends in merger reviews in China in the semiconductor space.

First, semiconductor transactions are less likely to be reviewed under the simple case procedure in China. Between 2016 and 2020, only 25 percent of all transactions concluded by SAMR did not go through the simple case procedure,22 while this number is much higher (55 percent) for semiconductor transactions.23

Second, compared to other industries, a higher percentage of semiconductor transactions are cleared with remedies in China. Between 2016 and 2020, only 1 percent of all transactions concluded by SAMR were approved with remedies,24 while 8.3 percent (6 out of 72 deals) of semiconductor transactions were approved with remedies.25

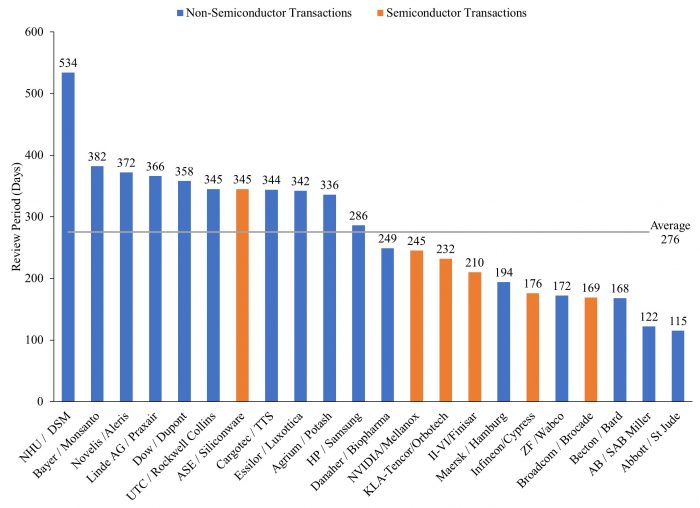

Third, among intervention cases, semiconductor transactions have not experienced longer review times than non-semiconductor ones in the last five years. As shown in Figure 2-1 below, among the 22 intervention cases concluded by SAMR between 2016 and 2020, the average review period was 230 days for semiconductor transactions and 293 days for non-semiconductor ones.26

Figure 2-1: SAMR’s Review Periods for Intervention Cases, 2016-202027

Source: SAMR and MOFCOM decisions, summarized by Compass Lexecon28

SAMR identified the following key characteristics and areas of enforcement associated with the semiconductor industry: 1) accelerated industry consolidation and increasingly more transactions,

2) highly concentrated markets with high entry barriers, 3) large percentage of conglomerate mergers that exacerbate the risk of bundling and tying, and 4) consideration of future technological development and industry characteristics when defining relevant markets and evaluating remedies.29

Indeed, SAMR’s primary competitive concern in semiconductor cases has been about bundling and tying. These semiconductor transactions typically involve complementary products from neighboring markets, and SAMR often raised concerns regarding foreclosure of competition via anti-competitive bundling and tying or reduced interoperability. For example, in Infineon/Cypress (2020), SAMR found that the parties have a neighboring relationship in the automotive-grade MCU market and the automotive-grade NOR flash memory market. SAMR raised concerns that the merged party could reduce the interoperability between their own automotive-grade NOR flash memory and third-party MCUs, thus leveraging its market power in automotive-grade NOR flash memory onto the market of automotive-grade MCUs and excluding competition therein.30

Remedies to address concerns over anti-competitive bundling and tying in semiconductor transactions in China include various behavioral remedies, such as commitments to no tying or bundling practices, continued supply of relevant products and services, and guarantees of interoperability.31 For instance, in KLA/Orbotech (2019), one of the remedies was to prohibit parties from tying or bundling their process control equipment with semiconductor deposition and etching equipment or apply any unreasonable conditions in the Chinese market post-transaction.32 In NVIDIA/Mellanox (2020), one of the remedies was to maintain compatibility of NVIDIA’s GPU accelerators and Mellanox’s internet devices with competitors’ products;33

Question 3: China has been very active in its antitrust enforcement against mergers in the internet space. How does it compare to those in the United States and Europe?

Recently, big tech companies’ acquisitions of small companies are under the spotlight in the United States and Europe. The key theory of harm is “killer acquisitions,” that is, big tech companies may pre-emptively eliminate future competition by acquiring nascent, disruptive competitors with transactions that typically do not meet the revenue-based merger control notification threshold. For example, the United Kingdom’s Competition and Markets Authority blocked Sabre’s proposed takeover of Farelogix on the basis that the merger would eliminate a technology innovator in the travel industry and “could result in less innovation in their services.”34 The United States FTC Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter recently described serial acquisitions of the small companies as a “Pac-Man strategy” and stated that “the collective impact of hundreds of smaller acquisitions can lead to a monopolistic behemoth.”35

SAMR has similarly recognized the potential negative consequences of killer acquisitions on innovation in the SAMR 2020 Report, stating that Chinese antitrust agencies may initiate investigations into mergers involving start-ups or emerging platforms even if they do not meet the notification threshold.36

Diverging from the United States and Europe, one of the key areas where Chinese merger review agencies have focused on is internet companies’ failures to notify mergers involving entities formed by the Variable Interest Entity (“VIE”) structure. VIE refers to a corporate structure where the controlling party does not own shares of the operating entity but maintains control through a series of agreements.37 Although the VIE structure has been prevalent among internet companies, its legality and compliance with foreign investment rules are questionable in China.38 As a result, many mergers and acquisitions involving VIE-structured companies were not notified in China. In late 2020, SAMR issued inquiries of past mergers for many prominent internet companies, including Alibaba, Tencent, Meituan, Baidu, ByteDance, and DiDi.39 China also published Antitrust Guidelines in the Field of Platform Economy (“Platform Guidelines”) in 2021, making it clear that mergers involving VIE structures are not immune to notifications.40 As of mid-October, in 2021, SAMR has fined 50 “fail-to-notify” transactions, most of which involved VIE-structured internet companies.41

In addition to enforcement on transactions involving VIE-structured companies, SAMR intervened in internet mergers based on competitive concerns. In July 2021, it blocked one merger and imposed remedies on another involving large digital platforms.42

While taking into account the unique characteristics of digital platforms, SAMR’s competitive analyses indicate that standard tools continue to play an important role for mergers involving large digital platforms. In particular,

- High market shares remain a crucial indicator for SAMR’s finding of market power, while incorporating unique factors associated with digital platforms. For example, in the blocked merger between Douyu and Huya, SAMR considered revenue, active users, and live-streaming resources to measure the parties’ market shares and found that the proposed merger would lead to a combined share of 70 percent in the live gaming market.43

- SAMR continues to apply the conventional theory of harm when analyzing the competitive effects of digital platform mergers. For example, the Tencent/China Music Corporation (“CMC”) transaction involved a horizontal combination of two online music broadcasting platforms. SAMR relied on diversion ratio analysis to conclude that Tencent’s QQ Music was a close competitor to CMC’s two music applications.44

Regarding remedies for mergers in the internet space, the Platform Guidelines identified a few data-related remedies to address competition concerns. For example, the parties could be asked to divest their data; open up their networks, data, or platform infrastructure; or modify their algorithms. As such, we may see some data-related remedies in China down the road on mergers involving digital platforms.

Question 4: The impact of M&A transactions on innovation has attracted a lot of attention globally in recent years. How does China analyze and address innovation concerns in its merger reviews?

From August 2008 to September 2021, Chinese merger review agencies approved 50 transactions with remedies. In 17 (or 34 percent) of these 50 transactions, SAMR expressed innovation concerns and imposed remedies accordingly. Out of these 17 transactions, nine were approved in the last five years.45 The following are a few observations regarding SAMR’s approach to addressing innovation concerns based on the publicly available decisions on these 17 transactions.

Broadly speaking, SAMR considers theories of harm related to innovation in both horizontal and vertical mergers. In horizontal mergers, the combined firm could have less incentive to innovate due to the elimination of an existing or potential competitor, resulting in reduced R&D, impediments to technological progress, or delays of the introduction of new products by the merging parties (“horizontal innovation concerns”). These horizontal innovation concerns are reflected in some recent decisions including Danaher/GE Biopharma (2020),46 Bayer/Monsanto (2018),47 and Dow/DuPont (2017).48 In vertical mergers where one of the merging parties was the owner of a key upstream input or patent, the combined firm could have the incentive to foreclose rival firms or block rivals’ innovation by refusing to license relevant technologies or degrading interoperability, among other ways (“vertical innovation concerns”). These vertical innovation concerns are reflected in the recent decisions including KLA/Orbotech (2019),49 Broadcom/Brocade (2017),50 and Nokia/Alcatel-Lucent (2015).51

Among intervention cases where Chinese agencies have specifically identified innovation harm, almost all have involved industries with the following characteristics: 1) high-tech products or services, 2) high market concentration, and 3) high entry barriers. High-tech sectors often require intensive R&D investment as firms compete to introduce innovative products and services to the market. In evaluating market concentration, Chinese agencies often raise innovation concerns when the parties’ combined market shares exceed 40 percent or when the merged entity’s post-transaction share ranks the highest in the relevant market. Lastly, when evaluating entry barriers, Chinese agencies often consider factors such as rivals’ technical strength, industry expertise, financial strength, R&D capacity, and IPR portfolio, as well as user switching costs.

Chinese agencies have utilized structural, behavioral, or a combination of both remedies to address potential innovation harm in transactions. In transactions with horizontal innovation concerns, remedies in China include divestiture (e.g. Bayer/Monsanto (2018)52), hold-separate (e.g. ASE/Siliconware (2017)53), or continuation of R&D operations (e.g. UTC/Rockwell Collins (2018)54). These structural and behavioral remedies aim to preserve the parties’ incentives to maintain pre-transaction innovation levels. For transactions with vertical innovation concerns, behavioral remedies include mandatory licensing of certain assets (e.g. Microsoft/Nokia (2014)55), maintenance of interoperability with rival technologies (e.g. Broadcom/Brocade (2017)56), and FRAND commitments (e.g. KLA/Orbotech (2019)57). These behavioral remedies aim to guarantee rival’s access to crucial upstream technologies for innovation and downstream manufacturing.

Click here for a PDF version of this article

1 Elizabeth Wang, Kun Huang and Sophie Yang are economists at Compass Lexecon. Aston Zhong is an assistant researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Science. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the views of any organizations or clients with which they are or have been associated.

2 SAMR, “2020 Annual Report of Antitrust Enforcement in China” [2020], p. 3, available at http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-09/24/5639102/files/77006c5bccc04555aa05f30c9a296267.pdf.

3 Average USD to RMB exchange rate between 2016-2020 was 6.7636. See FRED, “China / U.S. Foreign Exchange Rate,” available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DEXCHUS.

4 SAMR, “Interim Provisions for Merger Control Review” [2020], available at http://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/fgs/202010/t20201027_322664.html, and “The Regulation on Prohibiting the Abuse of IP Rights to Preclude or Restrict Competition” [2020], available at http://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/fgs/202011/t20201103_322857.html.

5 SAMR, “Guideline of the Anti-Monopoly Committee of the State Council for Countering Monopolization in the Field of Automotive Industry” [2020], available at http://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/fldj/202009/t20200918_321860.html.

6 SAMR, “Guideline of the Anti-Monopoly Committee of the State Council for Countering Monopolization in the Field of Intellectual Property Rights” [2020], available at http://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/fldj/202009/t20200918_321857.html.

7 SAMR, “Guideline of the Anti-Monopoly Committee of the State Council for Countering Monopolization in the Field of Platform Economy (Draft for Comments)” [2020], available at http://www.samr.gov.cn/hd/zjdc/202011/t20201109_323234.html.

8 SAMR, “Guideline of the Anti-Monopoly Committee of the State Council to the Commitments Made by Undertakers in Monopoly Cases” [2020], available at http://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/fldj/202009/t20200918_321855.html.

9 SAMR, “Guideline of the Anti-Monopoly Committee of the State Council to the Applicability of the Leniency System for the Horizontal Monopoly Agreements in Monopoly Cases” [2020], available at http://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/fldj/202009/t20200918_321856.html.

10 SAMR, “Guideline of the Anti-Monopoly Committee of the State Council to the Undertakers’ Antitrust Compliance” [2020], available at http://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/fldj/202009/t20200918_321796.html.

11 Note, “review” means “conclude” throughout this article. Thus, any case counts or periods do not include cases that are under review but not yet concluded.

12 SAMR 2020 Report, p. 41.

13 The number of transactions from 2008 to 2017 is sourced from the MOFCOM website. See http://fldj.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx/; and China Economic Net, “Briefing: List of Unconditional Approvals by MOFCOM since the Implementation of the Anti-Monopoly Law” [2014], available at http://intl.ce.cn/specials/zxxx/201408/12/t20140812_3340531.shtml. Number of transactions from 2018-2020 are sourced from the SAMR 2020 Report and decision notices on the SAMR website. See http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/ftjpz/. Note, total number of transactions in 2016 indicated on the MOFCOM website is larger than the sum of conditional approvals, unconditional approvals, and blocked transactions and a similar discrepancy exists in the 2018 data from SAMR. In both cases, the total number of transactions is set to be the sum of number of conditional approvals, unconditional approvals, and blocked transactions.

14 SAMR 2020 Report, p. 3. Note 1) the report stated the review period of 41.2 was for the latter years of 2011 and 2015 and it is omitted in text for simplicity; 2) the statistics in the report are internally inconsistent: it stated the average period was 24.2 days during 2016-2020 on page 3 and the average period was 24.2 for 2020 alone on page 15. The two figures are mathematically inconsistent with each other and are used as they are in this article.

15 SAMR 2020 Report, p. 3. Similar inconsistency exists as described in note 13 above and the length of the pre-notification period was also for the latter years of 2011-2015.

16 SAMR, “Press Conference on ‘Interim Provisions for Merger Control Review’ by the Head of Anti-Monopoly Bureau” [October 27, 2020], available at http://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/xwxcs/202010/t20201027_322668.html.

17 Between 2016-2020, the total number of cases concluded by SAMR was 2,147 (SAMR 2020 Report, p. 13), 1,611 of which were approved under the simple case procedure based on simple case announcements collected from the SAMR and MOFCOM websites by Compass Lexecon. Thus, the percentage of non-simple cases was 25 percent (536 of 2,147) and over 70 percent for simple cases.

18 The review period is defined as the number of days between SAMR officially accepting the notification to it making a final decision, as described in the decision notices published on the SAMR website. Such definition applies throughout this article.

19 SAMR 2020 Report, p. 43 and “2019 Annual Report of Antitrust Enforcement in China” (“SAMR 2019 Report”) [2019], p. 20, available at http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-12/25/5573435/files/195171fdee024615933c10d57f141171.pdf.

20 The review periods of intervention cases are summarized by Compass Lexecon from the MOFCOM and SAMR websites. See http://fldj.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx/ and http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/ftjpz/.

21 SAMR 2020 Report, p. 13.

22 Between 2016-2020, the total number of cases concluded by SAMR was 2,147 (SAMR 2020 Report, p. 13), 1,611 of which were approved under the simple case procedure based on simple case announcements collected from the SAMR and MOFCOM websites by Compass Lexecon. Thus, the percentage of non-simple case procedure is 25 percent (536 of 2,147).

23 Compass Lexecon summarized from the SAMR 2020 Report, p. 72.

24 Between 2016-2020, the total number of cases concluded by SAMR was 2,147, 22 of which were approved with remedies. See SAMR 2020 Report, p. 13.

25 Compass Lexecon summarized from the SAMR 2020 Report, p. 72.

26 The review periods are extracted from SAMR and MOFCOM intervention cases decisions and summarized by Compass Lexecon. See, for example, http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/ftjpz/ and http://fldj.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx.

27 The review period is defined as the number of days between SAMR officially accepting the notification to it making a final decision, as described in the decision notices published on the SAMR website.

28 Compass Lexecon summarized from the SAMR and MOFCOM websites. See http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/ftjpz/ and http://fldj.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx.

29 SAMR 2020 Report, pp. 74-75.

30 SAMR, “Notice of the State Administration for Market Regulation of the People’s Republic of China on the Conditional Approval of the Proposed Acquisition of Equity Interests of Cypress by Infineon Technologies” [2020], available at http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/ftjpz/202004/t20200408_313950.html.

31 Zhang, Gong &Yang, “Non-Horizontal Mergers in China: A Case Study of KLA-Tencor/ Orbotech,” CPI Antitrust Chronicle, [August 2019], available at https://www.competitionpolicyinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/CPI-Zhang-Gong-Yang.pdf.

Even in II-VI/Finisar (2019), a case in which the key concern was related to horizontally overlapping products, SAMR required the merging parties to commit to not discriminate customers in terms of price, delivery date, after-sales service, and other conditions, as well as to supply products at fair and reasonable prices. See SAMR, “Notice of the State Administration for Market Regulation of the People’s Republic of China on the Conditional Approval of the Proposed Acquisition of Equity Interests of Finisar by II-VI Incorporated” [2019], available at http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/ftjpz/201909/t20190920_306948.html.

32 SAMR, “Notice of the State Administration for Market Regulation of the People’s Republic of China on the Conditional Approval of the Proposed Acquisition of Equity Interests of Orbotech by KLA” [2019], available at http://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/xwxcs/201902/t20190220_290940.html.

33 SAMR, “Notice of the State Administration for Market Regulation of the People’s Republic of China on the Conditional Approval of the Proposed Acquisition of Equity Interests of Mellanox by NVIDIA” [2020], available at http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/ftjpz/202004/t20200416_314327.html.

34 United Kingdom Competition and Markets Authority, “Press Release CMA blocks airline booking merger” [April 9, 2020], available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/cma-blocks-airline-booking-merger.

35 Rebecca Kelly Slaughter, “Prepared Remarks of Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter Regarding Non-HSR Reported Acquisitions by Select Technology Platforms, 2010-2019: An FTC Study” [September 15, 2021], available at https://www.ftc.gov/public-statements/2021/09/prepared-remarks-commissioner-rebecca-kelly-slaughter-regarding-non-hsr.

36 SAMR 2020 Report, p. 63.

37 Zhong Lun Law Firm, “Is VIE an Obstacle to China Merger Filing?” [July 27, 2020], available at https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=2c9a2289-c996-4790-8c7f-ef7d790a4cef.

38 Chi Hung KWAN, “Why Are So Many Chinese Internet Companies Listed Overseas? The advantages and disadvantages of the VIE structure” [December 27, 2016], available at https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/china/16091401.html.

39 SAMR 2020 Report, p. 47.

40 SAMR, “Guideline of the Anti-Monopoly Committee of the State Council for Countering Monopolization in the Field of Platform Economy” [2021], Chapter 4, available at http://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/fldj/202102/t20210207_325967.html.

41 Compass Lexecon summarized from the SAMR website. See http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/xzcf/.

42 In July 2021, SAMR issued its decision prohibiting the merger between Huya and Douyu, available at http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/ftjpz/202107/t20210708_332421.html; in the same month, SAMR published its decision imposing remedies on Tencent’s acquisition of a controlling stake in China Music Group, available at http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/xzcf/202107/t20210724_333020.html.

43 SAMR, “Notice of State Administration for Market Regulation Decision on Blocking the Merger of Huya and Douyu International” [2021], available at http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/ftjpz/202107/t20210708_332421.html.

44 SAMR, “SAMR Decision for Administrative Penalty (2021) No. 67” [2021], available at http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/xzcf/202107/t20210724_333020.html.

45 Sourced from Chinese merger review agencies’ decisions (available at the MOFCOM and SAMR websites) and summarized by Compass Lexecon.

46 SAMR, “Notice of the State Administration for Market Regulation of the People’s Republic of China on the Conditional Approval of the Proposed Acquisition of GE Biopharma’s Life Science and Biopharmaceutical Business by Danaher” [2020], available at http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/ftjpz/202002/t20200228_312297.html.

47 MOFCOM, “MOFCOM Announcement No. 31 of 2018 on Anti-Monopoly Review Decision Concerning the Conditional Approval of Concentration of Undertakings in the Case of Acquisition of Equity Interests of Monsanto Company by Bayer Aktiengesellschaft Kwa Investment Co” [2018], available at http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/article/policyrelease/announcement/201803/20180302719967.shtml.

48 MOFCOM, “MOFCOM Announcement No. 25 of 2017 on Anti-Monopoly Review Decision Concerning the Conditional Approval of Concentration of Undertakings in the Case of Proposed Merger Between the Dow Chemical Company and E.I. Du Pont De Nemours And Company” [2017], available at http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/article/policyrelease/buwei/201705/20170502577349.shtml.

49 SAMR, “Notice of the State Administration for Market Regulation of the People’s Republic of China on the Conditional Approval of the Proposed Acquisition of Equity Interests of Orbotech by KLA” [2019], available at http://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/xwxcs/201902/t20190220_290940.html.

50 MOFCOM, “MOFCOM Announcement No. 46 of 2017 on Anti-Monopoly Review Decision Concerning the Conditional Approval of Concentration of Undertakings in the Case of Acquisition of Equity Interests of Brocade Communications Systems Limited by Broadcom Co., Ltd.” [2017], available at http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/b/c/201708/20170802632069.shtml.

51 MOFCOM, “MOFCOM Announcement No. 44 of 2015 on Anti-Monopoly Review Decision Concerning the Conditional Approval of Concentration of Undertakings in the Case of Acquisition of Equity Interests of Alcatel-Lucent by Nokia” [2015], available at http://fldj.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx/201510/20151001139743.shtml.

52 MOFCOM, “MOFCOM Announcement No. 31 of 2018 on Anti-Monopoly Review Decision Concerning the Conditional Approval of Concentration of Undertakings in the Case of Acquisition of Equity Interests of Monsanto Company by Bayer Aktiengesellschaft Kwa Investment Co” [2018], available at http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/article/policyrelease/announcement/201803/20180302719967.shtml.

53 MOFCOM, “MOFCOM Announcement No. 81 of 2017 on Anti-Monopoly Review Decision Concerning the Conditional Approval of Concentration of Undertakings in the Case of Acquisition of Equity Interests of Siliconware Precision Industries Co., Ltd by Advanced Semiconductor Engineering, Inc” [2017], available at http://fldj.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx/201711/20171102675701.shtml.

54 SAMR, “Notice of the State Administration for Market Regulation of the People’s Republic of China on the Conditional Approval of the Proposed Acquisition of Equity Interests of Rockwell Collins by UTC” [2018], available at http://www.samr.gov.cn/fldj/tzgg/ftjpz/201811/t20181123_332679.html.

55 MOFCOM, “MOFCOM Announcement No. 24 of 2014 on Anti-Monopoly Review Decision Concerning the Conditional Approval of Concentration of Undertakings in the Case of Acquisition of Nokia’s Device and Service Businesses by Microsoft” [2014], available at http://fldj.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx/201404/20140400542415.shtml.

56 MOFCOM, “MOFCOM Announcement No. 46 of 2017 on Anti-Monopoly Review Decision Concerning the Conditional Approval of Concentration of Undertakings in the Case of Acquisition of Equity Interests of Brocade Communications Systems Limited by Broadcom Co., Ltd.” [2017], available at http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/b/c/201708/20170802632069.shtml.

57 SAMR, “Notice of the State Administration for Market Regulation of the People’s Republic of China on the Conditional Approval of the Proposed Acquisition of Equity Interests of Orbotech by KLA” [2019], available at http://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/xwxcs/201902/t20190220_290940.html.