August 2019

CPI Oceania Column edited by Sam Sadden (CPI) presents:

Ten Things To Know About The ACCC’s Digital Platforms Inquiry By Prof. Caron Beaton-Wells (University of Melbourne)1

On July 26, 2019 the much-anticipated final report of the Australian Competition and

Consumer Commission (“ACCC”) in its Digital Platforms Inquiry (the “Inquiry”) was released (the “Report”).2

This article is an attempt to distil the 619 pages of the Report into ten key take-outs as relate to the findings and recommendations on competition.3 For those who can’t wait, here they are:

- Yes, in some respects, it is ground-breaking;

- It confirms what we already knew – Google and Facebook are big;

- But it also acknowledges their success;

- It sings from the international song sheet on substantial market power;

- But it rejects break up and proposes to contain power in other ways;

- Its central finding is that markets aren’t working;

- And it commits to playing the long game on enforcement;

- It is cool on regulating for competition;

- But it is hot on other regulatory measures;

- The work is just getting started.

Before proceeding further, it is important to point out that the Inquiry was not concerned with digital platforms at large. Its Terms of Reference directed the ACCC to study the impact of “digital search engines, social media platforms and other digital content aggregation platforms … on competition in media and advertising services markets.”4 That effectively meant the focus was on Google and Facebook.5

That said, many of the Report’s recommendations extend (deliberately) to digital platforms other than the two main protagonists and, if adopted, will affect economic sectors beyond media and advertising.6

Yes, in some respects, it is ground-breaking

The Inquiry has been hailed as “ground-breaking” and a “world first.” What is the basis for such hyperbolic claims? After all, there have been just shy of 30 such inquiries on the same or related topics published or announced around the world in the last five years.7

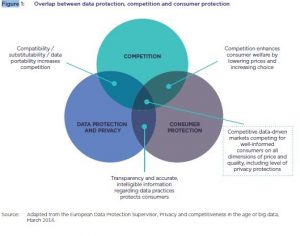

The feature that most distinguishes the ACCC’s endeavor is the breadth in its scope, traversing not just competition, but consumer protection, unfair trading, data protection and privacyrelated considerations, and, importantly, the intersections between them.

The significance of these intersections is captured in the following Figure in the Report:8

The Inquiry’s scope reflects the ACCC’s status as a multi-functional agency and one that takes an active and integrated approach to administering its responsibilities in each of its portfolio areas.

Moreover, in accordance with the Inquiry’s Ministerial mandate, the ACCC ventured beyond its standard parameters to consider public interest issues associated with a diversified and sustainable news and journalism sector.

Further features of the Inquiry which merit emphasis were its method in information gathering and stakeholder engagement and its level of detail. Within the relatively short time assigned for the formidable task (18 months), both were impressive on any measure.

The ACCC received 180 written submissions. It issued 60 statutory notices compelling the production of documents. It held eight public fora and commissioned a series of research reports and surveys. It also conducted innumerable meetings with individual firms, representative groups, and other regulatory agencies, in Australia and overseas.

Totaling 1036 pages of output, an Issues Paper (39 pages) was published in February 2018 and a Preliminary Report (378 pages) in December 2018. The Final Report (619 pages) was delivered to the Government six months later, in June 2019.

It confirms what we already knew – Google and Facebook are big

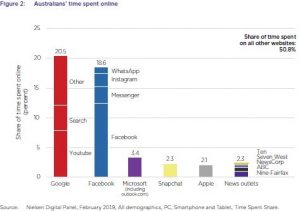

The Report logically commences with what have now become standard and unsurprising statistics on the size and pervasiveness of Google and Facebook in online usage and activity.

As of 2018, Google Search accounted for 90 percent of search traffic originating from Australian desktop computer users and over 98 percent of search traffic from Australian mobile users, while 84 percent of Australian adults access the Facebook platform at least monthly, with 54 percent accessing Instagram.9 Moreover, as depicted in the following Figure from the Report, the time spent on these two platforms was shown to “dwarf” the time spent elsewhere online.10

Google and Facebook account for 84 percent of the growth in the total online advertising market over the last five years. If classified advertising is excluded, this rises to 102 percent of the total market increase.11 It was estimated that for a typical AU$100 spent on online advertising (excluding classifieds), AU$47 goes to Google, AU$24 to Facebook, and AU$29 to all other websites.12

Google was found to have a 96 percent market share of general search advertising revenue,13 and Facebook to have a 51 percent market share of display advertising revenue in Australia.14

Almost half the population (43 percent) use online news as their primary news source,15 with 33 percent accessing news through social media, 20 percent through search, and 12 percent through news aggregators (such as Google News and Apple News), as compared to 30 percent accessing news directly from the websites of news organizations.16

But it also acknowledges their success

As is also now routine (and important), the ACCC acknowledged that the size of Google and Facebook reflects the innovative high-quality products and services they provide and the extent to which they are valued by consumers.17 It also recognized the significant complementary benefits that the platforms deliver for business users, including advertisers and news organizations.

Equally, having observed that Australians’ attachment to these platforms shows “no sign of slowing” and that investors apparently expect continued growth, the ACCC considered it necessary to point out that “it does not have concerns with digital platforms pursuing growth and profitability.”18

Indeed, since the commencement of the Inquiry, the Chairman has been at pains to acknowledge and applaud the platforms for their ingenuity and success.19

The Report also importantly emphasized that, under Australian competition law, it is neither illegal to possess substantial market power nor to outsmart less skillful and efficient rivals in the competitive process. However, it is illegal, according to the Report, “for a firm with substantial market power to damage this competitive process by preventing or deterring rivals or potential rivals from competing on their merits.”20

Section 46(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (CCA), as amended in 2017, in fact provides that a “corporation that has a substantial degree of power in a market must not engage in conduct that has the purpose, or has or is likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition” in a relevant market. The scope of the amended section is yet to be properly tested.

There is reference in the Report to firms with substantial power having a “special responsibility” in relation to their conduct. This invocation of a central tenet of European abuse of dominance law is interesting given that, on its face at least, there is no such requirement in the Australian provision.

The Report is also replete with references to the European Commission’s cases against Google as well as the Bundeskartellamt’s decision against Facebook for abuse of dominance. However, such references should not be read to imply equivalence between Article 102 of the European competition rules and Section 46 of the CCA. In particular, Article 102 encompasses some types of conduct that may be characterized as unfair or exploitative abuses. Even in its amended form, Section 46 is unlikely to extend that far, not least because in Australia unfair trading practices are dealt with under the Australian Consumer Law, in provisions that the Report recommended be strengthened and extended.21

The ACCC’s brief was not to consider whether any firm has acted in breach, or even potentially in breach of the provisions of the CCA. Such consideration is for an investigation of specific conduct with reference to specific facts and evidence. Moreover, in Australia, liability for any such breach can only be determined by a court in a proceeding brought by the ACCC (or a private plaintiff).

The report disclosed that the Commission has five investigations of possible breaches, one in connection with a potential misuse of market power and four in connection with potential contraventions of consumer law. It is expected these investigations will be concluded “later in the year.”22

It sings from the international song sheet on substantial market power

In analyzing their multi-sided business models, identifying relevant markets, and determining whether Google or Facebook has substantial power in them, the ACCC joined the chorus of similar inquiries around the world to date.23

In relation to Google, it found that the firm has substantial power in a general search services market and a search advertising market in Australia. Facebook was found to have substantial power in a social media services and a display advertising services market. In each case, it was found that the power of these firms is non-transitory.24

Needless to say, the ACCC rejected submissions of Google and Facebook that they compete in broader markets.25

The reasoning in support of the substantial market power findings was familiar also. In the case of each platform, the ACCC identified the following factors as relevant:26

- same-side and cross-side network effects and associated positive feedback loops;27

- in the case of the general search market, consumer inertia exacerbated by default and pre-installation settings;28

- brand strength;29

- extreme economies of scale and sunk costs;30

- advantages of scope and conglomeration effects, including as arise through data accumulation, multiple user touch points across the web, and integrated advertisingrelated services;31

- strategic acquisitions that have either entrenched power in core markets (through the acquisition of potential competitors particularly) or enabled expansion into related markets;32 and

- in the case of the search and display advertising markets, the highly fragmented structure of each market in which Google and Facebook each have substantial shares relative to competitors and the fact that users tend to single-home on each of these platforms.33

Separately, the ACCC singled out Google and Facebook’s access to personal data as a significant competitive advantage, highlighting the volume, quality, granularity, and diversity of such data as being a source of considerable value to each firm.34 It is this data, the Commission observed, that enables both firms to offer highly targeted and personalized advertising that in turn constitutes their primary source of revenue.

The Commission firmly rejected the opposing position, namely that data is ubiquitous, nonrivalrous and low cost to collect, and is not of itself inherently valuable (as distinct from the skills required to extract relevant and actionable insights from it).35

The Report characterized these various factors as raising barriers to the entry of new rivals or expansion of existing ones.

Relatedly, it rejected the argument made by both firms that each is subject to constraints from dynamic competition. While not excluding the possibility of disruptive innovation in the relevant markets, the ACCC took the view that both Google and Facebook are substantially insulated from competition, at least in the short to medium term.36 It also saw the prospects of disruption as less probable than in early phases of internet competition given the persistence and scale of the current incumbents (Google especially).37

Moreover, in view of competition being “for” rather than “in” the market, the ACCC pointed out that concerns about competitive risks would not be ameliorated by the mere replacement of Google and Facebook by another dominant firm.38

But it rejects break up and proposes to contain power in other ways

The ACCC fulsomely rejected the submissions of some stakeholders that the platforms be subjected to structural separation.

The Commission took the view that such a remedy was laden with risks of unintended welfare-reducing consequences. It also considered it doubtful at best that divestment would effectively address the competition and consumer concerns identified in the Report.39

However, reflecting a similar emphasis in other reports, the ACCC expressed a concern that the existing power of digital platforms not be extended by anti-competitive acquisitions.

It adhered to its preliminary recommendation that Australia’s merger law be amended to identify additional factors to be considered in the review of proposed acquisitions, namely:40

- the likelihood that an acquisition would result in the removal from the market of a potential competitor;41 and

- the amount and nature of assets, including data and technology, which the acquirer would likely have access to as a result of the acquisition.42

The Commission acknowledged that the existing law enables such factors to be considered. However, it regarded the proposed amendment as useful “to signal to merger parties, the courts and the Tribunal the need to consider these factors in considering whether an acquisition will substantially lessen competition.”43

This recommendation does not go as far as recommendations made in other reports in relation to competition law upgrades to tackle the challenges posed by digital power and acquisitions. In particular, it does not encompass considerations such as reducing the standard of proof or reversing the burden of proof as is contemplated elsewhere.

Relatedly, the Report does not directly tackle the challenging issues raised by the uncertainty of the counterfactual where the target is a young and small-scale operation.44

These omissions are explained by the fact that the ACCC is actively considering broader questions in relation to the merger regime and whether it should advocate for legislative changes that would have economy-wide effect.45 Such changes could involve a rebuttable presumption that an acquisition will substantially lessen competition in cases involving markets with high levels of concentration.46 The ACCC may be aided in this advocacy if it had a program of ex post review of merger decisions. The agency is out of step with many of its major counterparts in not having such a program.47

The ACCC also confirmed its preliminary recommendation that, in the absence of a compulsory notification scheme, Google and Facebook be requested to voluntarily provide notice of acquisitions of any business with activities in Australia and provide it with sufficient time to review the acquisition.48

Google was not opposed to providing advance notice. Facebook did not respond.

The ACCC acknowledged concerns about unintended effects on innovation and investment commonly raised in response to more aggressive merger control in digital markets. In deference to such concerns its final recommendation was that the notification protocol between the ACCC and each platform would specify the types of acquisitions covered (including any minimum transaction value) and the minimum advance notification period prior to completion of the proposed transaction.49

Further, the ACCC repeated its threat that if the proposed undertakings from Google and Facebook were not forthcoming, it “will make further recommendations to Government to address this issue.”50

In addition to these merger-related recommendations, the Preliminary Report had proposed changes to address consumer inertia owing to default settings for search engines on internet browsers and for internet browsers on operating systems.51

Confirming but qualifying its proposal (to confine it to Google), the Report recommended that the search company provide Australian users with the same options being rolled out to Android device users in Europe, that is the ability to choose their default search engine and default internet browser from a number of options.52

The ACCC’s decision to narrow its recommendation on this issue was in acknowledgement of concerns that its scope could have adverse effects, including raising barriers to expansion for existing smaller suppliers of search services that are vertically integrated with an internet browser and in turn further entrenching Google’s power in the browser market.53

Its central finding is that markets aren’t working

Key questions that the ACCC identified for itself in the Inquiry were whether either Google and Facebook “are exercising their market power in their dealings with advertisers and content creators” and what might be “the price or non-price effects of this.”54 Expressed in these terms, it might have been assumed that the ACCC was embarked on a standard consumer welfare analysis.

However, the Report does not in fact answer those questions directly. Its findings are more holistic, reflecting the wide mandate given to the ACCC in the Inquiry, the breadth of its portfolio, and its corresponding institutional charter, encapsulated in the pithy mission statement: “making markets work.”55

In accordance with this broader purview, the ACCC found that, as a consequence of the platforms’ power, markets are not functioning as efficiently as they would be absent such power.

Google and Facebook each were said to have the ability and incentives to act in ways that threaten the competitive process. They have the freedom to raise prices or reduce quality and/or to anti-competitively leverage power to favor their own products and services at the expense of rivals.56 Having referred to price and quality, somewhat surprisingly, the Report did not canvas the effects of the platforms’ power on the pace and nature of innovation.57

In addition, the degree of opacity in the relevant markets were said to undermine confidence and trust that are crucial to effective market operation and risk the distortion of competition by penalizing firms that do operate transparently.58

Underscoring its view on market functioning, the ACCC emphasized substantial imbalances in information and bargaining power for each of the affected user groups vis-à-vis the platforms.

Consumers have insufficient information and are unable to make meaningful choices about the collection and use of their personal data. While there are different levels of awareness and different preferences among consumers concerning privacy, most are concerned about the lack of transparency and their lack of choice in relation to platform data practices. There is particular concern relating to the extent of online and location tracking and sale of data to third parties.59

Media organizations are forced to accept unfavorable terms concerning the ranking and display of news content, notice of algorithmic changes, formats that affect content monetization, access to user data, and the timing and process for take-down of copyright infringing material.60

In addition, the media industry is heavily regulated while virtually no regulation applies to the platforms despite their active participation in the online news eco-system. This regulatory disparity is a further imbalance with distortionary effects on competition.61

For advertisers there is a lack of transparency in ranking and display practices by the platforms, issues with measurement and verification of advertising performance, limited ability to negotiate on prices, and a risk of anti-competitive self-preferencing of the platforms’ own ad inventory and ad tech services.62

The ACCC made it clear that its concerns regarding leveraging of market power were not confined to advertisers and that there are risks (and some evidence) of such conduct with anti-competitive effects across the wide range of markets in which digital platforms (and not just Google and Facebook) operate.63

In addition to potential abuses on the platform, the Commission noted submissions raising misuse of market power allegations within markets in which the platforms have substantial power, including foreclosure of access to data by competitors, restrictive clauses in contracts with third party websites and restrictions on user switching. It hinted that these may be matters for investigation in Australia in the future.64

And commits to playing the long game on enforcement

Despite the strong language of the Report and the ACCC Chairman in his press conference announcing its release,65 the Inquiry has not made recommendations for any significant changes (yet) to Australia’s competition law.

Consistent with a number of other reports, the ACCC took the view that “the existing goals and tools” of the legal framework “remain applicable to digital markets.”66

However, unlike some of its counterparts, the Report did not suggest that there needs to be a shift in approach to error cost so as to favor enforcement notwithstanding risks of false positives. This is unsurprising given that, under the current Chairman, the ACCC has a proven track record of embracing litigation risk and testing the law in grey areas.67

The ACCC’s central proposal to contain the risks it had identified was that it invest in a more pro-active, concerted, and sustained effort to monitor, investigate, and, where there is evidence of a breach of the law, bring enforcement proceedings against digital platforms.68

In support of this proposal, the ACCC pointed out that there are conditions in digital platform markets that are likely to strain the effectiveness of existing prohibitions (the misuse of market power prohibition particularly) and that reinforce the need for something other than a “business as usual” approach. Five such conditions were identified:

First, competition law is insufficient to deal with market failures that arise due to a lack of transparency or due to externalities in other markets. Furthermore, a lack of transparency may mean that potential breaches of the law go undetected.

Second, effective enforcement will require a body of data amassed over time to assess competition matters. Proactive monitoring and collection of data will enable the ACCC to build an evidence base for future assessments under existing competition laws.

Third, investigations can take a significant amount of time and by the stage at which they are complete, it may be too late to effectively remedy the competition concern. Developing knowledge and industry expertise may result in more timely outcomes when using existing competition laws as it will reduce the learning curve for the agency.69

Fourth, existing laws rely on conduct to be brought to the ACCC’s attention. It is likely that some discrimination will not be able to be detected by market participants. This possibility is heightened where digital platforms operate as “black boxes” and exacerbated where participants are reluctant to air their concerns.70

Finally, some conduct may not substantially lessen competition but there may be public benefit nevertheless in reporting on that conduct. The ACCC may want to highlight conduct that has the potential to substantially lessen competition in the future, or which may suggest that a firm with substantial market power is taking advantage of the imbalance of bargaining power in a way that causes significant detriment to user groups.

The ACCC identified four ways in which to deal with these challenges:

- The creation of a specialist digital platforms branch within the ACCC to maintain consistent scrutiny and investigation of issues relating to digital platforms.71 The branch would have a mandate directed at monitoring and enforcing compliance with both the consumer protection and the competition rules.72

- The ability to proactively investigate and gather information. This will enable the investigation of broader issues and enable the ACCC to investigate potential market failures as well as potential breaches of the CCA where information has not been forthcoming through complaints by market participants.

- The ability to periodically compel data from digital platforms. Similar to other industries, such as telecommunications, there is seen to be value in having compulsory powers to gather information from digital platforms to facilitate the monitoring of market developments, and assist in informing decisions.

- The ability and resources to publicly report on issues of concern that may fall beneath the threshold of breaching the CCA, and to make recommendations based on evidence gathered by the branch, to the Government and other relevant regulators.

The branch would direct its attention to “all” digital platforms, even if the initial focus would be on Google and Facebook.73 This was justified by the fact that some but not all of the issues the ACCC had identified were dependent on market power and enabled the ACCC to side-step the thorny issue of identifying criteria to determine which firms warrant additional scrutiny or regulation.74

It is cool on regulating for competition

There is a growing view around the world that robust competition law enforcement in digital markets needs to be complemented with regulatory measures and some jurisdictions have already taken steps in this direction.

The ACCC’s view on regulation is more cautious.

Its Preliminary Report recommended the establishment of a new regulatory authority tasked with monitoring, investigating, and reporting on the criteria, commercial arrangements, or other factors used by “relevant” digital platforms in dealings with advertisers and media organizations.75

This approach met with strong criticisms, not least from Google and Facebook in relation to the possibility of having to disclose their proprietary algorithms and the risk of algorithmic gaming.76 Others raised questions about the effectiveness of such an authority,77 including risks of capture.78

In its final analysis, the ACCC retreated from this recommendation. It took the view that it was the appropriate body to carry out the functions of “shining a light”79 and reporting on platform practices, while also taking any enforcement action where there is evidence such practices involve an infringement of competition or consumer laws.

It justified this position by reference to its existing skills and expertise in the relevant areas as well as its existing relationships with key regulators in adjacent fields, including the Australian Communications and Media Authority (“ACMA”) and the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (“OAIC”). Evidently, these relationships have been strengthened by the experience of working together in the Inquiry.80

Moreover, the ACCC made clear that a substantial aspect of the new branch’s work would be continuing to study digital platform markets, starting with a five-year study of the ad tech supply chain, which could result in recommendations to Government for regulatory action.81 The ACCC was also temperate on the need for other pro-competition regulation.

It was not convinced that imposing data portability requirements would have a significant effect in ameliorating barriers to entry and expansion in digital platform markets in the short term. It also noted that Google and Facebook already voluntarily provide users with the capacity to access and port their data.82

However, it did concede that data portability (as well as interoperability) could spur new entry and innovation and undertook to consider recommending to Government that the recently introduced Consumer Data Right be extended to digital platforms in the future.83

But it is hot on other regulatory measures

The foregoing could give the false impression that the Report was “light touch” in respect of regulation generally.

The ACCC was prepared to recommend that Google and Facebook be required to negotiate enforceable codes to govern their dealings with media organizations, a process to be overseen by ACMA which would also have responsibility for code enforcement.84

In addition, it recommended a mandatory code to facilitate copyright enforcement on platforms.85

In relation to issues concerning “disinformation” the agency recommended that the platforms establish an industry code to govern complaints, failing which, a mandatory code for this purpose should be introduced.86

It further recommended that there be a prescribed minimum standard for platform internal dispute resolution processes and the additional support of an ombudsman scheme to deal with complaints and resolve disputes that consumers and small businesses have in relation to scams and advertising services.87

Arguably most significantly, the ACCC recommended sweeping changes to update Australia’s outmoded Privacy Act 1988.88 In addition to this economy-wide reform, it proposed a special code for all digital platforms supplying search, social media and content aggregation services to address particular concerns regarding their notification and consent processes.89

If this strategy of “attack by code” is to have any prospect of success, there will need to be genuine “buy-in” by the platforms. The ACCC has allowed for Google and Facebook to play a role in code development but has also proposed time limits on patience in this regard. Inevitably, there will be issues with finding a sensible middle ground between motherhood statements and over-prescription in code provisions. As recommended by the ACCC, there also will need to be a serious threat of meaningful sanctions for code breaches.

Doubtless, there will be reactions to the proposed regulatory onslaught that draw attention to its associated costs and possible chilling effects. In connection with the privacy proposals, there is also likely to be consternation that those costs necessarily will fall on businesses other than the digital platforms, including advertisers and media organizations.90 The platforms, after all, have GDPR-proofed their operations already.

Conscious of these risks, the ACCC has proposed its close involvement in the process of code development and law reform that is otherwise to be led by ACMA and the OAIC. That involvement will be crucial in attempting to balance the various interests at stake.

The platforms themselves are likely to have strong views about the proposed regulatory burdens and will be tested in their stated commitment to support regulation.91

The work is just getting started

In releasing the Report, the Government accepted “the ACCC’s overriding conclusion that there is a need for reform – to better protect consumers, improve transparency, recognize power imbalances and ensure that substantial market power is not used to lessen competition in media and advertising services markets.”92

It also accepted that there is a need to develop a harmonized media regulatory framework.

The Government announced a 12-week consultation process to receive and consider feedback from stakeholders before it issues a more detailed response, together with a roadmap and timetable for implementation of recommendations that are accepted. This deferral and engagement are warranted given the breadth and depth of the Report.

The Government is likely to accept the recommendation that there be a specialist digital platforms branch in the ACCC and that it have the powers and resources to do the work as laid out by the Commission in the Report.

The recommendations concerning merger control are also not expected to cause much trouble, even if there may be some tweaking around the edges.

It would be surprising if Google refused to extend the benefit of its default setting changes to Australian Android users. However, the Government and the ACCC may also need to take a close look at how Google has designed those changes given that, as they are proposed in Europe, they may in fact have little impact on competition in the search engine market.93

There is also unlikely to be much hesitation by the Government in accepting the need for an overhaul of Australia’s general privacy framework.

However, given the scope, complexity, and cost involved in the swathe of regulatory recommendations, a challenging process of stakeholder engagement lies ahead.

Regardless of the outcomes of this process, what is pellucidly clear is that the ACCC’s work on digital platforms is just getting started.

Click here for a PDF version of the article

1 University of Melbourne. Comments and questions welcome to c.beaton-wells@unimelb.edu.au.

2 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, Digital Platforms Inquiry, Final Report, June 2019, at https://www.accc.gov.au/focus-areas/inquiries/digital-platforms-inquiry/final-report-executive-summary.

3 The Report’s detailed discussion of reforms to Australia’s privacy and consumer laws (ch. 7) are largely excluded from this article. Those parts of the Report that deal with choice and quality of news and journalism (ch. 6) and identify issues in connection with artificial intelligence and other emerging and new technologies (ch. 8) are also not canvassed.

4 See https://www.accc.gov.au/focus-areas/inquiries/digital-platforms-inquiry/terms-of-reference.

5 Currently, Amazon’s presence in online advertising in Australia is relatively small (see pp. 96-97). The Report only considered Apple in the context of Apple News as a digital content aggregator and its consideration was relatively marginal given that, as compared with other platforms, the user base of Apple News is not significant (see p. 43).

6 See pp. 452-453

7 This number encompasses inquiries that have been undertaken or commissioned by national governments, parliamentary committees and competition authorities. It excludes the additional substantial number of studies and reports that have been published on related topics by regional and international intergovernmental organizations, including the OECD, BRICs, and the World Bank. It also excludes reports by private think tanks, institutes, and other such bodies such as the World Economic Forum and the University of Chicago’s Stigler Center.

8 See p. 5.

9 See p. 42.

10 See p. 6.

11 Google’s share of online advertising spend is just less than double (51 percent) that of Facebook (24 percent) (see p. 46).

12 See p. 122.

13 See p. 89.

14 See p. 97.

15 See p. 52.

16 See p. 55. These were statistics derive from an external report. The ACCC’s findings from its own consumer survey suggest they were conservative.

17 The Report attempts to estimate the value of platforms to consumers (as well as the value that consumers bring to platforms) but also acknowledges the methodological challenges and limitations of any such estimates (see pp. 47-51).

18 See p. 7.

19 See, e.g. the comments of Rod Sims on the Competition Lore podcast, at https://competitionlore.com/podcasts/accc-inquiry-into-digital-platforms/. See also https://www.accc.gov.au/media/video-audio/digital-platforms-inquiry-media-conference.

20 See p. 60.

21 It was recommended that the ACL be amended so that unfair contract terms are prohibited (not just voidable, as currently). This would mean that civil pecuniary penalties apply to the use of unfair contract terms in any standard form consumer or small business contract. See Recommendation 20 (p. 37). It was recommended also that this prohibition be supplemented with an additional unfair trading prohibition targeting specific practices concerning the collection and handling of data. See Recommendation 21.

22 See p. 38.

23 It is evident that the ACCC paid close attention to the analysis in and findings of such inquiries. In particular, the Report makes repeated reference to the Furman Report (see Jason Furman et al., Report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel, Unlocking digital competition, March 2019) and the Cremer Report (see Jacques Cremer et al., Competition policy for the digital era, April 2019).

24 See ch. 2.

25 However, it did retreat from its preliminary finding of an additional, “news referral services” market in which it had also found both firms to have substantial power (see pp. 103-105). The ACCC decided it was unnecessary to reach a definitive view on such matters (although it also said that they still regarded them as “probably” correct (p. 99)). Nevertheless, the Commission did find that the platforms have substantial bargaining power in their dealings with media businesses. This conclusion was based on the view that, in the context of the mutually beneficial exchange between the parties concerned, news organizations need Google and Facebook more than the platforms need the former. This was found to be the case in relation to Facebook despite the social media network having only a 25 percent share of news referrals at the time of the Preliminary Report and that share having fallen to 16 percent by the time of the Final Report (see p. 104). For the news industry, the platforms were said to be critical and “unavoidable trading partners” (the Report is peppered with this catchy phrase).

26 Listed here in the order in which they appear in the Report.

27 See pp. 66-68 (Google); p. 79 (Facebook). In relation to same-side network effects, the ACCC identified these arising for Google as a result of data accumulation which enables it to improve its search algorithm and thereby enhance the quality of its search results which in turn attracts more users, allowing for even greater data accumulation and enhancement effects (pp. 66-67).

28 Google’s has default settings for its search engine on both the Chrome and Safari browsers. Together these two browsers account for more than 80 percent of the Australian market for browsers. Google pays a substantial fee to Apple for using Google Search as the default search service on Safari, estimated globally as US$9 billion in 2018 and US$12 billion in 2019 (p. 69). Chrome is pre-installed on Android devices (owned by Google), as a result of which the Google search engine is the default on over 95 percent of mobile devices (40 percent Android; 55 percent Apple iOS) in Australia (see p. 70). Beyond the issues raised by default settings, ch. 7 of the Report contains a more detailed discussion of the issues raised by behavioral biases on the part of consumers in connection with data collection and use and privacy settings (not just confined to the digital platforms).

29 See pp. 72-73 (Google); p. 79 (Facebook).

30 See p. 73 (Google); p. 79 (Facebook).

31 See pp. 73-74 (Google); pp. 79-80 (Facebook).

32 See pp. 74-76 (Google); pp. 80-81 (Facebook).

33 See pp. 89-99.

34 See pp. 84-89.

35 See p. 87.

36 See p. 66 (Google); p. 77 (Facebook).

37 See p. 78; p. 84.

38 See p. 76.

39 See pp. 116-117.

40 The merger provisions in the CCA already refer to “the dynamic characteristics of the market, including growth, innovation and product differentiation” as a factor to be considered in determining whether an acquisition is likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition (see s 50(3)(g), CCA).

41 The ACCC rejected criticisms of this proposed merger factor that raised concerns about the emphasis on a potential “competitor” as distinct from potential “competition” and the prospects that the amendment would result in false positives and a chilling of competition (see p. 105).

42 See p. 105. The second factor was broadened from just a reference to “data” in the Preliminary report by way of recognition that data is one of a number of assets that may be a source of competitive advantage and so as to ensure that the proposed factor is sufficiently flexible and forward-looking, as well as suited for application across the economy (see p. 108).

43 See p. 106.

44 In relation to these issues the Report does not entertain the adoption of a “balance of harms” test, as recommended by the Furman report in the UK. However, in a recent speech referencing that report, the ACCC Chairman did say that “if the prospect that the target will become an effective competitor is small, but the potential increase in competition and consumer welfare is large, greater weight should be put on the potential for competition.” See https://www.accc.gov.au/speech/address-to-the-2019-competition-law-conference.

45 The ACCC’s success rate in persuading Australian judges to block acquisitions that it considers are likely to substantially lessen competition has been poor. In light of this, the ACCC has long harbored concerns that its evidentiary burden in such matters is too onerous (see https://www.accc.gov.au/speech/law-council-ofaustralia). More recently, it has been critical of the fact that, even where anti-competitive effects are identified in connection with an acquisition, the courts and Tribunal are prepared to allow it to proceed based on behavioral commitments which the ACCC has argued would not be sufficient to overcome structural concerns (see https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/court-dismisses-accc-proceedings-opposing-rail-freightconsolidation).

46 See p. 109.

47 See https://theconversation.com/are-too-many-corporate-mergers-harming-consumers-we-wont-know-ifwe-dont-check-115378.

48 See p. 109. This reflected the ACCC’s concern that it may not have an opportunity for advance review of acquisitions where either company chooses not to notify the Commission (a likely explanation as to why none of the acquisitions about which the ACCC expresses concern in the report (including Facebook’s acquisitions of Instagram and What’s App and Google’s acquisitions of Youtube and DoubleClick) were reviewed in Australia).

49 The ACCC also made it clear that it would not necessarily undertake a public review of every transaction of which it is notified pursuant to the protocol (see p. 110).

50 See p. 109.

51 See p. 109.

52 This change is being undertaken by Google in response to the European Commission’s ruling in the Android case. See https://blog.google/around-the-globe/google-europe/supporting-choice-and-competition-europe/.

53 See p. 111.

54 See p. 60.

55 See https://www.accc.gov.au/about-us/australian-competition-consumer-commission/about-the-accc.

56 See pp. 137-138. While the ACCC did not find that Google or Facebook have used this ability or acted on these incentives in Australian markets, it pointed repeatedly to cases in which Google and Facebook have been found to have done so with anti-competitive effects in Europe (see e.g. pp. 133, 137, 140).

57 However, there was discussion of innovation in the context of the proposed privacy reforms, the ACCC expressing the view that greater privacy and data protection would shore up consumer trust in data practices which in turn would provide the environment in which data-driven innovation can flourish (see p. 455).

58 See p. 138.

59 See ch 7.

60 See ch 5.

61 See ch 4.

62 See ch 3.

63 See pp. 133-136.

64 See p. 137.

65 See https://www.news24.com/World/News/australian-watchdog-calls-for-controls-on-facebook-google20190726.

66 See p. 13. See further https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/competition-law-should-remain-focused-onconsumer-welfare.

67 See https://www.accc.gov.au/speech/accc-future-directions.

68 See pp. 140-142.

69 The ACCC noted that this may be a significant benefit given the international experience regarding the time and resources other competition agencies have needed to conclude cases, pointing in particular to the European Commission’s Google Shopping case, in which the initial complaint was lodged by Foundem in November 2009, the European Commission officially opened its investigation in November 2010, and only came to a decision in June 2017 (see p. 139). Additionally, the ACCC pointed to its experience with other industries as confirming the view that there is significant benefit in having staff dedicated to specific sectors. By devoting resources to assess the conduct of digital platforms and proactively investigating issues in the markets in which digital platforms operate, more timely resolutions, capable of addressing competition concerns before they become entrenched, may be possible.

70 Such reluctance was observed by the ACCC in the course of the Inquiry (see p. 14).

71 The recommendation is consistent with digital capacity-building initiatives under way in competition authorities around the world. It also bears resemblance to the proposal of a Digital Markets Unit in the Furman Report. However, that report left open the question of whether such a unit would be housed within or separate from the Competition and Markets Authority and it also ascribed more of a regulatory than enforcement role to the proposed new body.

72 This compass is important given that these two sets of rules “are closely linked and mutually reinforcing.” It is also important given the particular significance for consumer protection in the presence of acute information asymmetries and bargaining imbalances (see p. 339).

73 See p. 141.

74 Cf the Furman Report’s jurisdictional concept of “strategic market status.”

75 “Relevant” platforms were defined as platforms which generate more than AU$100 million in revenue per annum.

76 See, e.g. https://www.smh.com.au/business/companies/unworkable-unnecessary-unprecedented-facebookhits-back-at-accc-20181212-p50lvk.html; https://www.smh.com.au/business/companies/google-slams-newscorp-algorithm-review-board-hopes-20181029-p50cpw.html.

77 See, e.g. https://theconversation.com/accc-wants-to-curb-digital-platform-power-but-enforcement-is-tricky107791.

78 The ACCC itself acknowledged this risk (see p. 29).

79 See p. 140.

80 See the ACCC’s reflections on this at p. 29.

81 For example, the development of codes of conduct to govern such relationships, similar to that proposed in the Furman Report.

82 See p. 115.

83 See pp. 115-116.

84 Recommendation 7 (see ch. 5).

85 Recommendation 8 (see ch. 5).

86 Recommendation 15 (see ch. 6).

87 Recommendations 22-23 (see ch. 8).

88 Recommendations 16 and 17 (see ch. 7).

89 Recommendation 18 (see ch. 7).

90 For businesses dependent on collecting personal data, the bombshell hidden in the fine print is the recommendation that consent settings be pre-selected to “off,” effectively introducing an opt-in mechanism for data collection (recommendation 16(c) (see p. 456)).

91 See, e.g. John Davidson, “We won’t stand in the way of regulation, pledges Facebook,” Australian Financial Review, July 2, 2019, p. 19.

92 See http://jaf.ministers.treasury.gov.au/media-release/082-2019//.

93 See https://www-bloomberg-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.bloomberg.com/amp/opinion/articles/2019-08-02/google-android-search-engine-auction-a-cheeky-response-to-eu (referring to https://www.android.com/choicescreen/).